April 18, Easter 3B (Luke 24:36b-48)

In case flesh and bone aren’t enough to convince the disciples, Jesus also asks for dinner.

The day my mother died I was performing the part of Juliet in my freshman English class. I was wearing a plaid shirt I’d taken from my grandfather, which I had ruined by washing with a piece of gum in the pocket. I kept wearing it anyway, probably because my mother wasn’t there to tell me not to, just as she had not been there to wash it properly in the first place, just as she was not there to see me as Juliet. Looking up from my book I saw a face in the oblong window of the classroom door and recognized my neighbor, Sammy. There was only one reason for Sammy to be there. He had been charged with taking me to the hospital if her condition worsened.

I’ve told that story countless times, recounting the mundane details—Shakespeare, the ruined shirt, the oblong window. These are my last clear memories for a very long time. After we came home from the hospital without her, my mind goes dark.

“Obliterative” is how Joan Didion describes the shocking nature of grief following her husband’s death in The Year of Magical Thinking. And it’s true, as Didion says, that even the funeral was not as difficult as I had imagined it would be, cocooned as I was in the unreality of the loss. A friend later told me I made a joke at the grave site, but what kind of monster would do that? Who laughs beside their mother’s grave? Someone who believes the whole situation is absurd, that’s who.

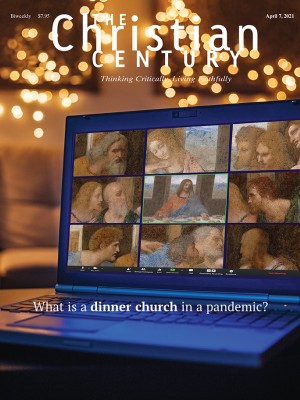

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

“We might expect that we will be prostrate, inconsolable, crazy with loss,” Didion writes of the early days of grief. “We do not expect to be literally crazy, cool customers who believe their husband is about to return and need his shoes.” I know a woman whose husband died of a heart attack on the treadmill; she wondered anxiously what to do with the sandwich she later found in his car. He’s forgotten his lunch, she thought. That’s the absurdity of grief.

It’s in those days when we are “literally crazy,” when we are wondering if the dead would like a sandwich, that it seems anything could happen—that death may, in fact, be reversible. We half expect to find the dead at our usual stations. We may even be driven to find them. After the death of my friend’s child, I went to Target and walked the aisles absentmindedly until I realized I was looking for her baby.

I remember all these absurdities when I read Luke’s account of the days following Jesus’ death. I imagine the disciples to be in that “literally crazy” phase of grief as they go about their daily tasks. But for them, the dream of the grieving comes true. The grave is found empty. And then Jesus goes and does what we wish any of our beloved dead would do. He appears, again, in their midst. He chats with them on the road to Emmaus. He joins them for a meal.

The disciples are terrified, as we would surely be if the dead stood before us. Despite the foretelling in the scriptures they haven’t yet understood, despite the devastation of their loss and their desire for the undoing of it, they still think they’re seeing a ghost. What else can appear suddenly on roads, walk through doors, or vanish at will?

But Jesus is not a ghost, and Luke takes care to show him demonstrating this. “See that it is I myself,” Jesus says. “Touch me and see.” And if his flesh and bone are not enough to convince them, he also asks for dinner. He eats their fish. Imagine the shocked silence around that table while a dead man resumes his daily round. Imagine Didion’s husband appearing in their bedroom and requesting his shoes or my mother appearing at the door with a bag of groceries. Would I scream before I touched her hands and looked for the familiar spray of freckles on her arms? How much proof would I require? How long would it take for my horror to become the joy the disciples feel at Bethany?

Still half-crazed from the trauma of loss, they seem to accept that they’re living in a new order where the dead can not only rise, walk, and talk theology with friends—the dead can live. The dead can eat. This is what delights me most about the Gospel ghost stories. In Catholic school we were taught that the risen Jesus had no more need of food than Didion’s husband had of his shoes, that he eats simply to prove he is not a specter. The church fathers seemed to think of digestion as a vile complication of mortality. But I like to think Jesus eats because he loves eating with his friends. Jesus enjoys these reunions as much as they do.

The resurrected body of Christ is at once a new reality and a restoration of what life was like before it was so brutally undone. He returns the disciples from Didion’s obliteration to the simple details of everyday life. His presence answers their questions about who he is, but it also gives back, for a time, the friend they knew and mourned. When they arrive at Bethany, they see him carried into heaven, a second departure from their company, and yet Luke writes of their joy.

Maybe the resurrection promises a restoration like this for all of us, in the end, and I will get another chance to read the part of Juliet, but the pocket of my plaid shirt will be clean, and when I look to the window, it will be my mother’s face that I see.