Common threads among five prophetic voices of the 20th century

“We turn to Thurman, Bonhoeffer, Day, Heschel, and Niebuhr because they never let us forget the important questions.”

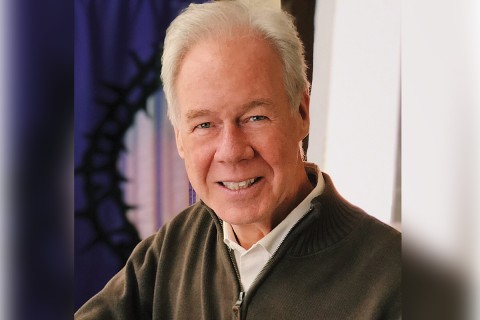

Over the last 30 years, Martin Doblmeier has directed more than 25 documentary films on religion and spirituality. He won Emmys for two films, one on the Washington National Cathedral and another on Howard Thurman. In 2012 he received the Daniel J. Kane Religious Communications Award. His five-part series Prophetic Voices—films on Thurman, Dietrich Bonhoeffer, Dorothy Day, Abraham Joshua Heschel, and Reinhold Niebuhr—is now available as a digital box set.

Why should people watch the Prophetic Voices series of documentaries?

The subjects of these films are genuinely remarkable figures, whose lives and spiritual journeys intersected with some of the most dramatic moments in the 20th century. Their lives offer a window into how people of faith confronted the issues of their day and, in so doing, offer us inspiration as we confront our own struggles.

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

These people are from a very different time than our own. In the 1940s and ’50s, 76 percent of Americans attended religious services. Recently that number fell below 50 percent for the first time. How are these leaders relevant to us?

Too many of us find it easier to keep our heads down and avoid harsh realities. Rather than looking for the expedient, political solution, these people asked themselves: What is the moral response? What all five of these figures have in common is a refusal to be indifferent to the challenges around them. To a person, they armed themselves with their traditions, called upon God to reveal to them his will, and then went forth to do what they felt needed to be done.

Where do you think Dorothy Day, Howard Thurman, and the others would be in today’s political landscape?

Thurman, having been raised along the Atlantic coastline, would be a great public champion for the environment. He wrote beautifully and often about how we, as humanity, continue to “soil our own nest.” Day would be on the steps of the Capitol fighting for the growing number of poor in the richest country in the world. Abraham Joshua Heschel would be marching to support Black Lives Matter. He would be thrilled to see today’s pioneering interfaith work but heartbroken at the continued public display of hatred toward Jews. Reinhold Niebuhr would call for a pox on both houses of Congress for their selfish behavior that always comes at the expense of the American people. Dietrich Bonhoeffer would confront the apathy in our churches with sermons so powerful he would ignite a new spark.

I found that watching the Bonhoeffer film first and ending with Niebuhr brought things full circle, both chronologically and theologically. Do you recommend watching these films in a particular order?

There is no particular order you need to watch them in. Niebuhr is one of the more common threads. He was a professor at Union Theological Seminary when Bonhoeffer came to America, and they became close friends. Niebuhr was devastated when he heard of Bonhoeffer’s execution. When Thurman was at Howard University, he regularly invited Niebuhr to travel down and preach, so the two became close. Niebuhr had a historic friendship with Heschel—the two were famous for taking long walks on Riverside Drive in New York and discussing the most vexing issues of the day. And Susannah Heschel recalls coming home to find Day at the Heschel home being entertained by her parents.

One theme that plays out is the role and limits of nonviolence. These leaders reacted very differently to World War II. Bonhoeffer became a de facto assassin. Day opposed violence, even if it was directed at Hitler. Heschel, a Jew, concluded that God still loves humanity in a deeply personal way.

It has been one of the great, consistent mysteries surrounding the Bible that, through the centuries, gifted and sincere people can read the same texts and come away with very different conclusions. Early in his ministry, Niebuhr identified himself as a pacifist. That later changed, and he was one of those who rang the bell early as Nazi Germany was readying for war. Niebuhr understood that the only way the German war machine would be stopped was with military might.

Bonhoeffer longed to be a pacifist. He even planned at one point to travel to India to study nonviolence under Gandhi. But fate took him in another direction, and ultimately he supported the violent overthrow of the Nazis. Heschel openly admitted that given the opportunity to kill Hitler, he would do so. Having lost his mother and three sisters to the Nazi horror, who could blame him? Thurman held fast to a nonviolence position yet wrote pastoral letters supporting soldiers—especially Black soldiers—in the field. Of the five, Day was the outlier.

You’ve said that it’s your responsibility as a storyteller to learn from the lives you document. What do you take away from these conflicts?

That is the challenge of the filmmaker, isn’t it? To remain faithful to the story despite those times you feel at odds with your subject. In my mind, pacifism was impossible to justify in the face of the Nazi atrocities. Day campaigned for the right of women to vote and even risked her life in the campaign. But then, throughout her own life, she never voted. I think voting is a sacred privilege too many people fought for—and some are still being denied today—for us to ignore. But we turn to these figures today not because they had all the answers. Faith is not about answers. We turn to them because in the midst of the turbulence of the 20th century, they never let us forget the important questions.

What other common themes should people watch for?

In the film, Pulitzer Prize–winning historian Taylor Branch says that Heschel was a “theological Hemingway” who wrote in “short, pithy aphorisms of enormous power.” Heschel was not the only one who could lay out theology in language that could strike a memorable chord in the reader. Whether it was Heschel writing “Some are guilty, but all are responsible” or Niebuhr writing “Man is mortal. That is his fate. Man pretends to not be immortal. That is his sin”—each wrote profound ideas in ways that remain with us today. There is a remarkable genius in that.

A version of this article appears in the print edition under the title “Wisdom of the prophets.”