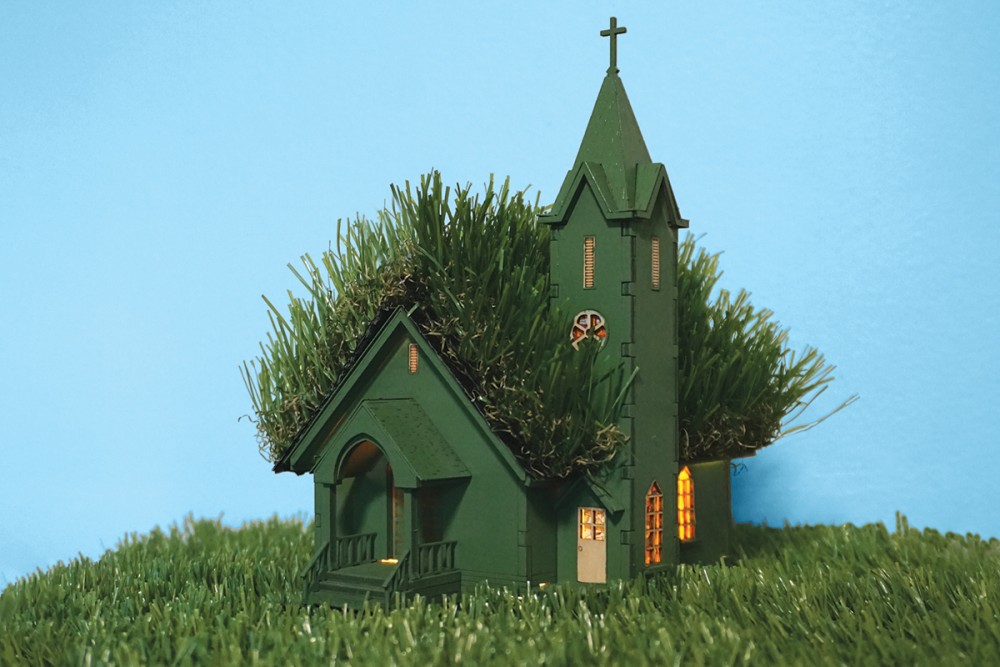

What does it mean to be a green church during a climate crisis?

It’s a way of life. But it starts small.

At Presbyterian-New England Congregational Church in Saratoga Springs, New York, environmental sustainability is woven into every aspect of church life, from how the church is heated to what happens at coffee hour to the content of sermons to what products are purchased for events. Being a green church has become a way of life, not an issue to be debated.

The pastor, Kate Forer, said that church members began this work several years ago by exploring together a series of questions that helped them to connect the dots between their actions and the entire network of creation. Where does our electricity come from? Are there opportunities for us to buy renewable energy, as a congregation and as individuals? If not, how can we as a church work to make those available? What are we doing with our trash? Are there ways to reduce our trash and increase our recycling and composting? What about transportation to church?

They asked these local questions and then connected them to the global ones. How are we advocating for environmental stewardship in our community, state, nation, and world? What justice issues do we need to tap into? Climate change is already affecting people, leading some to seek refugee status and asylum in other countries—what are we doing to support them? How do we help people in other communities have access to clean water?