A theology of ghosts

My sister talks to our dead mother. I am happy they both stand in the presence of love.

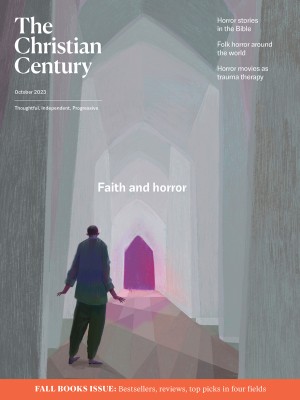

(Photo by Jr Korpa on Unsplash)

My sister has Prader-Willi syndrome. It’s kind of like Down syndrome with a bad attitude. At 68 years old, Dinah is the oldest living person with PWS. She’s sweet, loving, and funny. She’s an artist and a mystic. She is also neurodivergent and has limited speech capacity. She can be overwhelmed with self-directed anger. (Think about a time in your life when you lost it. Now multiply that tenfold. That’s a PWS outburst.) Once a caregiver tried to exorcise the “demon” of Dinah’s PWS by tying her to a tree. Ever since, she reminds me to “watch out for the mean man,” as if she can see his devilish approach.

Dinah and I were born 14 months apart, Irish twins. Our mom died 11 years, two months, and 13 days ago, as of this writing. Our grief is intertwined. In the weeks after the funeral, Dinah began an ongoing conversation with our mother. She tells Mom what’s happening in her life: she’s been to a dance party, she made a jewelry box, her friend is sick. After each event she relays, there’s a pause. Then Dinah answers a question no one else has heard.

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

It’s a cute story, unless you’re the one sitting next to my sister while she is talking to our dead mother. When the words start to flow an eerie presence emerges, and the world around us seems to disappear.

I wasn’t surprised to discover that my sister is fey. The weird kind of floats through our family—epigenetic maybe. On the night our uncle died, my mother saw him at the foot of her bed. She thought it was a dream, but the next morning her sister called to say their brother had been killed in the night during a routine military exercise at Fort Hood, Texas (now Fort Cavazos). In my work as a priest, spiritual director, and consultant on a project with neuroscientists through the Templeton Foundation, I’ve been called “a facilitator of the woo.” We can’t have the weird without the woo.

All theology is speculative, some is experimental, but the cornerstone of any theology is experience—experience that includes my sister’s conversations with our ghostly mom and my mom’s reported apparition of the dead. Our notions of God have always included personal experience of the weird and the woo: Joseph the patriarch and Joseph the carpenter both had visions of directive angels in their dreams; Mary experienced the annunciation, the Magi, and the star; Jesus met the Spirit in a dove. Experience first, theology second.

In each of the three mystical traditions of Abraham, the voices of the spirits have sung in the mystical choir of the weird. In Judaism, Abram heard YHWH call him into the desert. Moses responded to the burning bush, then went to Egypt to perform some serious magic. Samuel was summoned from the dead to offer advice to King Saul. Caleb was one of the 12 spies sent into the land of Canaan. The Talmud expands on the memory—the spy prayed at the burial cave of Abraham and Sarah, seeking their mercy. And in the Zohar, two sages—Rabbi Yehuda and Rabbi Aba—passing a grave meet the tomb’s occupant, who wants to know if his prayers have been posthumously answered.

Islam began when Muhammad meditated in a cave and had a revelatory vision of the angel Gabriel, who announced that he was the Messenger of God. The “Greatest Master” of Sufism, Ibn al-Arabi, spent hours in cemeteries sharing stories with the dead. He was adept in the art of himmah, concentrated imagination that aligns with the creative power of the Divine in order to affect the likes of the miraculous and the paranormal. In Ibn al-Arabi’s experience, altered states afford communication with the dead. The Sufi mystic recounts inviting his master teacher to join him at the cemetery, to sit between the tombs “talking with the spirits who keep me company.” The master was overwhelmed by the experience. But then he blessed Ibn al-Arabi with a kiss and acknowledged that the conversation with the dead had been mutually worthwhile.

Christians refer to God as the Holy Ghost. Jesus had conversations with Satan and Moses and Elijah. From the beginning of Christianity, mystics have prayed to their saints. And in some Christian traditions, the celebration of the Holy Eucharist includes summoning the communion of saints to the table of the Lord. On All Saints’ Day, I have invited congregants to place pictures of their deceased loved ones on the altar as a material reminder that they join us there. Together we celebrate “The Hymn of the Universe,” not to make holy cookies for the righteous but for the sake of what Teilhard de Chardin called the healing of the “Divine Milieu”: the living, the dead, and the cosmos.

On a hot July day in Tempe, Arizona, someone broke into the outdoor columbarium in our parish courtyard and stole the ashes from two niches. The police had never heard of such a thing. They took a report, looked for fingerprints, and suggested we contact some local mortuaries for advice. Parishioners, who needed a logical explanation for such a heinous crime, surmised that the thieves took the ashes for the copper in the urns.

Privately, one person told me they believed that evil spirits stole the ashes. This parishioner remembered that two decades before I had arrived as pastor, a priest had seriously violated clerical ethics. Rumors about the reasons for the pastor’s indiscretions were numerous, but the consistency of the painful and strange stories always caused this storyteller to cringe with nausea. When the abuse came to light, the priest was immediately removed. A significant number of the congregation followed with a rapid exodus.

I consulted a colleague and friend who had experience with unhealthy church spirits. He taught me to write special prayers for the cleansing and blessing of the space around the perimeter of the church, the desecrated columbarium, the ancillary buildings, the sanctuary, and especially the chancel. My colleague said these prayers were necessary to expel any demonic forces, especially considering the grossly inappropriate acts of the priest from years past. In other words, we exorcized the space to drive out the unwanted demons.

Shortly after the ritual, the person who believed that evil spirits had stolen the ashes whispered to me how much “lighter” the space felt. But over the course of the next few years, on random occasions, someone would mention experiencing an “odd sensation,” typically in the sanctuary or around the columbarium. We repeated the ritual of cleansing as often as deemed necessary.

I have long wondered what made the spirits at the parish “unclean” in the first place and why they would return just to be cast out again. Jesus said that when one unclean spirit is cast out, it will wander in the desert looking for a place to rest. When it finds none, it will return home. When the spirit then finds the house clean, it will go and find seven other demons more evil than itself and return. Did our demon really bring its friends to our church?

Remembering my sister’s exorcism, I began to wonder: What if these spirits were not demons at all but the souls of those who had been abused by a wicked priest? Had I made the spirits of Tempe into enemies by exorcising them when all they desired was love?

I know a priest whose church is set in the middle of a cemetery. Every All Hallows’ Eve, he walks through the resting place of the dead and asks if any of the inhabitants would like to receive the Rite of Reconciliation—the ritual of being loved into the beloved. I imagined our church’s spirit wandering in the Arizona desert, recounting how it had been mistreated by the mean man or abused by the priest. Maybe it continues to return to church in an attempt to cleave to love, only to be cast out again and again. Instead of exorcism, I thought, I should have held a healing service. We should have extended the love that the spirits so desperately ached to experience.

I began to think of ghosts as souls yearning to be united with divine love. Julian of Norwich knew that all that is “ghostly and bodily” needs love, that all that is love is contrary to the fiend. When my sister speaks with my mother, I know they each stand in the presence of love, as my mother’s brother did when he appeared at her bedside. For all things shall be well in love that abides, forgives, sustains, and heals. All things—including the bodily living and the ghostly dead.