Prayers rising past the immanent frame

Charles Taylor helps me understand my church’s architecture—and my own struggles with faith.

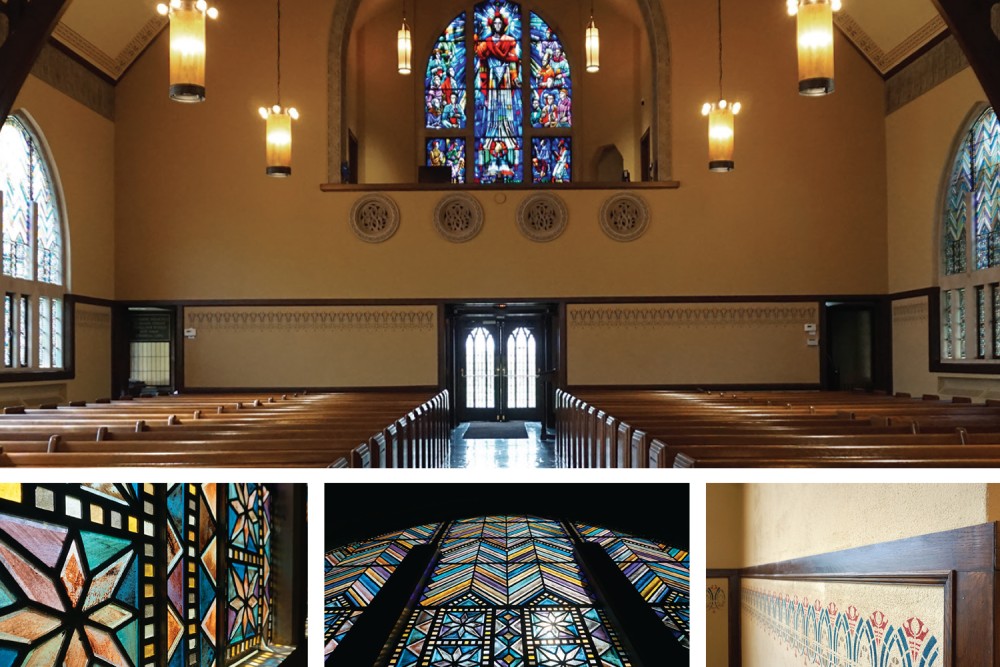

The sanctuary at First Congregational Church of Western Springs, in Illinois, was designed by Prairie School architect George Grant Elmslie and completed in 1929. (Century photos by Daniel Richardson)

I have served on the pastoral staff of First Congregational Church of Western Springs for more than a dozen years. In that time, I’ve heard my colleague Rich recount the origin of our sanctuary dozens of times. We intentionally regale every new member class with the story. The space itself is architecturally significant, as a placard by the entry doors notes: designed by the American Prairie School architect George Grant Elmslie, the building is on the National Register of Historic Places.

Sometimes I feel sheepish about our pride in our sanctuary and its impressive architect. (Did I mention that Elmslie worked with Frank Lloyd Wright and Louis Sullivan? No? Must have been an oversight.) But, as the church architect E. A. Sovik writes, “Beauty evokes in us the sense of the holy. So artists and priests are companions in every religion.” Or as Rich likes to say, beauty is a portal to the Divine.

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

Elmslie was an agnostic who was more interested in the paycheck than religious companionship. When the congregation first contacted the architect in the mid-1920s, they wanted a neo-Gothic structure. After all, the neo-Gothic Tribune Tower in nearby Chicago had recently been completed, and it had renewed the American appreciation for buttresses and gargoyles. Elmslie, however, despised neo-Gothic style. As he admonished the building committee in a letter preserved in our church archives, “Gothic was once truly great architecture, but neo-Gothic is a bloodless simulacrum of what was once great architecture.”

So the clever architect designed a sanctuary he knew the Congregationalists couldn’t afford. Once the indignity of the gaudy blueprints was out of the way, Elmslie designed a second version that borrowed a few less-offensive Gothic influences, such as a cruciform shape, but was dominated by his preferred Prairie style.

In addition to an earthy color scheme, organic ornamentation, and natural materials, the most distinctive aspect of the sanctuary is its horizontal emphasis. When he gets to this part of the story, Rich extends his arm toward the back of the room and invites the new members to notice how a stringcourse formed of wood and stone runs along the entire periphery of the space. Until the organ pipes were installed, the only object above the stringcourse was a very Prairie cross, decorated with birds and leaves.

Here Rich pauses dramatically and invites the group to remember a time they’ve entered a Gothic cathedral. “Where is your attention drawn?” he asks, sometimes unable to stop his hand from ascending in an obvious hint. Upward, of course. Vast Gothic cathedrals emphasize the transcendence of God, but Elmslie’s masterpiece invites us to direct our attention a little lower than the angels: to the gathered congregation. Perfect for a Congregational church that believes in collective wisdom, community discernment, and autonomous governance.

Integrating theological and ecclesial principles is not a bad way to wax poetic about church architecture, especially in light of our aforementioned tendency toward pride. Apparently this was a thing before the cornerstone was laid for the new sanctuary; according to the National Register of Historic Places documentation, the congregation aimed for a space that would “not only be efficient and an ornament to the village, but . . . a contribution to church architecture in America.” I deeply appreciate the beauty of the sanctuary, but I still find this ambition a bit fulsome.

It was only when I started reading Andrew Root’s Ministry in a Secular Age trilogy that I began to see the celebrated stringcourse with new eyes. The books riff on the philosophy of Charles Taylor, who lays out how the last 500 or so years have sent our culture reeling into unprecedented secularity.

Churches often get stuck thinking about secularity in insufficient terms. We think the issue is convincing people to spend their Sunday mornings in sanctuaries instead of doing the Wordle in bed or schlepping their kids to another travel hockey tournament. But Taylor observes a more radical shift: it’s not just a matter of religion losing ground to secular priorities. The “secular age” curbs our capacity to believe in God at all.

Quoting James K. A. Smith, Root explicates the fundamental architecture of late modern secularity. “The immanent frame is ‘a constructed social space that frames our lives entirely within a natural (rather than supernatural) order. It is the circumscribed space of the modern social imaginary that precludes transcendence.’” I cannot help but interpret that horizontal band of wood and stone as a visible symbol of the immanent frame, encasing my congregation in a disenchanted world.

I adore my congregation. It is made up of some of the dearest souls I’ve ever known, and I consider myself remarkably lucky to have been called here. I am unusually free to follow my pastoral instincts and creative whims; you should have seen the party they threw when I published a book, and when I decided a few years ago that I wanted to add “yoga instructor” to my ministry portfolio, they were like, OK, cool! So I speak this truth in deep and abiding love.

Several years ago, when our leadership engaged the services of a church consultant to lead an all-church survey in preparation for a strategic visioning process, many were startled by the results. We were off the charts in nearly every factor of congregational vitality: hospitality, morale, conflict management—you name it, we aced it. Except for one lone category, which we essentially failed: spiritual vitality.

Many rebuffed this feedback. Surely, the survey was flawed, its questions obviously meant for a more theologically conservative congregation. And maybe it was—but I’m not so sure. On my worst days, I fear we are playacting a nominal Christianity.

I can only say this because, even as an ordained pastor, I’ve personally spent years playacting a nominal Christianity. To be sure, I’ve wanted to believe. I’ve longed to encounter God and shake off my steadfast skepticism. But one of the reasons I get along so well as one of the pastors here is because I am swimming in the same secular sea. I am trapped under the same immanent frame.

For years my spiritual life—or lack thereof—was a source of shame and sorrow. Even while I thrived as a preacher and pastoral caregiver, I felt like a fraud. I wanted to believe in everything I proclaimed to be true about God, but I couldn’t force that desire to bloom into faithful fruition. I couldn’t even pray. I once scribbled these words in my journal:

I do not pray. I don’t know how to pray. I don’t like to close my eyes, clasp my hands, and start talking in my head toward God. Even when I am desperate, rarely do I mention anything to God. God and I are not on speaking terms. I’m like the quirky, solitary, yet totally productive worker in the cubicle on the third floor. Never actually talks to the boss, and the boss seldom thinks about him except to vaguely acknowledge gratitude that the worker is such a company man. I want to do the work of God on earth, to be part of the saints marching in—there just isn’t much for us to talk about in the meantime.

I really was a company man—wholly dedicated to serving the church, but inexplicably secular to my core.

Inexplicably secular, that is, until I was introduced to the integral question of the Taylorian project: “Why was it virtually impossible not to believe in God in, say, 1500 in our Western society, while in 2000 many of us find this not only easy, but even inescapable?” Learning how the contours of modernity had impaired my faith began to dislodge my shame. Maybe there wasn’t something fundamentally wrong with me after all? (Yes, I am an Enneagram 4.) Maybe it wasn’t our fault we flunked spiritual vitality? Just as the stringcourse was a visible reminder of the immanent frame, that third-floor cubicle I’d imagined struck me as an even more claustrophobic symbol of the same.

I am in a radically different place with my faith these days. I have been transformed, in the sense Root describes in The Congregation in a Secular Age: “Transformation, in the Christian tradition, comes from outside the self, relating to the self with an energy beyond the self. . . . Transformation is the invitation into grace.”

Perhaps it’s better to say I’m being transformed. A multitude of factors have contributed to this transformation: a pandemic collapse, a sabbatical restoration, an immersion in the pastoral theology of Eugene Peterson, mental health care, a growing intimacy with the Psalms, and a handful of providential friendships.

More than anything else, I would say that my transformation is a gift from God—but one that only became possible to receive when I had the language to name the architecture of secularity. In appreciating the cubicle of my personal faith and the stringcourse of my congregation, I was able to intentionally cultivate a conviction that these frames do not have to be closed. I think I’ve vacated the cubicle altogether, as abruptly as if a fire alarm demanded evacuation (or as abruptly as if a stay-at-home mandate forced exile). Still, faith can never escape fragilization. As ethicist Matthew Rose puts it, “Secularism means that our Christian experience is now shaped by a lurking uncertainty.”

It’s only fair to finish the story of First Congregational Church. Construction on the sanctuary was completed mere months before the Wall Street Crash of 1929. Suddenly, the congregation couldn’t afford their mortgage. By the mid-1930s, with a quarter of the nation unemployed, they’d uninstalled the telephone and slashed the pastor’s salary in half. (Here, Rich jokes that such a drastic action should only be taken in the most dire of circumstances.)

The congregation’s 1934 budget was a third of where they projected they would be, but they increased two line items: mission, because they knew they had more neighbors in need than ever before, and education, because they believed the Christian formation of their children was tantamount even in a season of scarcity. And so the story becomes not one about a cruciform building (albeit a magnificent one). It becomes a story of cruciform ministry, one that I trust is emblematic of who we are as a congregation, even in this secular age.

The stringcourse might be particularly stark on Tuesday evenings when we gather for those new member classes. But on Sunday mornings it is delightfully mitigated by light shining through jewel-toned columns of stained-glass windows. Light from light, true God from true God. On a recent Sunday, the sun cut at the right angle to color parishioners’ hair bright pink, blue, and gold.

Perhaps this is a perfect reminder that even when the eye is drawn to the gathered congregation, the Holy Spirit still dances within and among us, inviting us into grace. How beautiful, I thought. How beautiful.

This essay was made possible by the Relevance to Resonance: Exploring The Practices of Transcendence in Ministry and Congregational Life Lilly Endowment grant in association with Luther Seminary.