Mary’s special child and mine

I probably shouldn’t treat my own son like he’s the Messiah. Imagine the pressure.

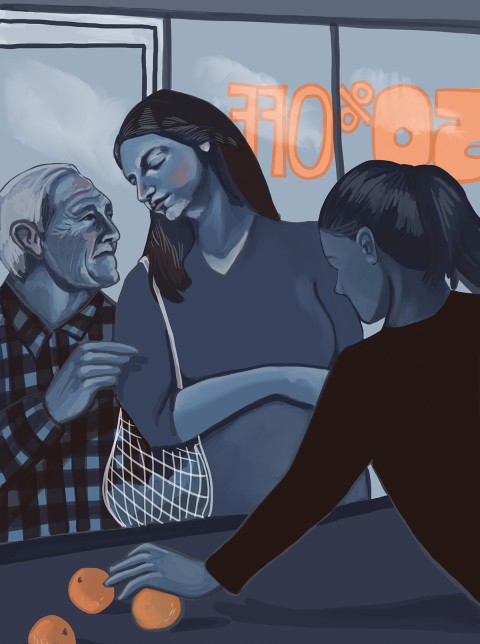

(Illustration by Martha Park)

While I stood in line at Dollarama, clutching a shower curtain to spread across our bed for my upcoming home birth, a man behind me asked, “How’s the baby doing?”

“Good.” I turned to face him. “Kicking a lot.”

“That’s a good sign!” he said in an accent I couldn’t identify. “Maybe he will be the Savior.”