Listen to the survivors

Some churches are starting the long process of reckoning with their role in the horrors of Indigenous boarding schools.

When the suspected unmarked graves of 215 Indigenous children were discovered last year on the grounds of the former Kamloops Indian Residential School in British Columbia, the news was met with widespread grief and outrage. All across North America, reckoning with the legacy of these boarding schools, which were often religious, has become a social movement—one led by survivors, their children and grandchildren, and tribal leaders.

“We are engaging in a collective moment here, the likes of which we have never seen before,” said Samuel Torres, deputy chief executive officer of the National Native American Boarding School Healing Coalition (NABS). The organization has been a focal point for advocacy, organization, and dialogue in the United States. “This is definitely a truth-telling moment that . . . has political and spiritual components to it.”

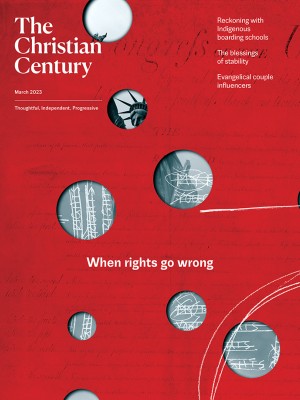

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

An enrolled member of the Osage Nation, Jimmy Beason is a professor in the Indigenous and Native Studies Department at Haskell Indian Nations University, itself a former boarding school in Lawrence, Kansas. Three of Beason’s grandparents attended these schools, though they never spoke about their experience. The point of the boarding schools, he says, was “cultural erasure. They were set up for the specific purpose of assimilating the minds and attitudes of Native children into a White American thought process in terms of promoting individualism, Christianity, private property ownership, nuclear families.” The goal was to break down traditional teachings and replace them with White identity and White understandings, said Beason.

A federal study released this spring identified 408 schools with federal support and more than 50 associated burial sites in the United States. NABS has also identified institutions that didn’t receive federal funds, including religious groups, which puts the number of known schools for Native children currently at 509, said Torres. “Christianizing” Indigenous children was an important part of this endeavor. Even federal schools were dominated by a culturally Protestant approach.

Historian Kathleen Holscher, who has studied Catholic missions, said that the “civilizing” project was primarily a Protestant one, but that as Catholics became increasingly integrated into the American religious landscape throughout the 20th century, they also allied themselves with the government’s goal of erasing Indigenous children’s culture and identity.

In June 2021, US Secretary of the Interior Deb Haaland, the first Native American to serve as a cabinet secretary, announced an initiative to investigate the history of institutions that she said had impacted generations of Indigenous families.

As the role the boarding schools played in American life has become public, Indigenous educators, tribal leaders, survivors, and others have become the public face of an American reckoning—whether they would have sought that role or not.

Maka Black Elk, executive director for truth and healing at Red Cloud Indian School in Pine Ridge, South Dakota, is one of those people.

At Red Cloud, community members follow a four-stage truth and healing process that is rooted in Indigenous scholarship, notably that of Maria Yellow Horse Braveheart at the University of New Mexico. That process has been adapted by other organizations as well.

The first stage is confrontation, in which an institution admits wrongdoing and a platform is created where survivors can share their stories. In stage two, survivors’ stories need to be processed and understood by their descendants and others who are not survivors. After that, survivors and descendants are asked to work out what symbolic or literal outcomes would help them. Finally, in the fourth stage, individuals and communities can start to establish changed relationships and construct a rebuilt community.

At the moment, Black Elk says, almost all institutions, including Red Cloud, are only in the early stages of confrontation and truth telling.

“We really have to think about what we need to be and do differently,” Black Elk said, but change is difficult and slow. Records are hard to obtain. In the case of Red Cloud, Jesuits kept the records. “Their perception of what they were doing probably wasn’t in line with what was happening,” Black Cloud said. Instead stories of abuse got passed down orally in families. Excavations at Red Cloud are underway to look for potential remains.

Broadly speaking, said Torres, “there is a significant volume of skepticism, because the way in which Indigenous peoples of these lands have been viewed, treated, and ultimately just perceived by Christian folks on these lands has been one of exploitation largely.” At the same time, he said, it’s necessary to “come to the table earnestly and in good faith,” recognizing that there is a tremendous diversity of practice—including some Christian practice—within Native communities. “It comes down to what each nation wants for its people.”

That diversity was reflected in the mixed reception of Pope Francis’s visit to Canada last year and his apology to Indigenous people there for the abuse they had suffered at Catholic hands. For its part, NABS responded with caution and a call for “actionable steps” that would be more significant than words.

“One has to be really, really cautious not to jump too fast to reconciliation. Truth telling has to happen before reconciliation,” Holscher said.

Churches and other religious institutions that perpetuated the cultural erasure of Native Americans owe Indigenous people much more than an apology, Beason said. “Churches have been complicit in historical tragedies that are affecting us today, [and they] still have a responsibility to remedy those atrocities. Concrete restitution, you know, no more just apologies.”

That being said, he also noted that a lot of Native Americans don’t want to be associated with Christian institutions because of this trauma, so building relationships can be difficult.

One group of Catholic sisters is attempting to find a way to tell the truth about their own organization. One day, Sr. Eileen McKenzie, the president of the Franciscan Sisters of Perpetual Adoration, received a call from a local historical journal asking her about the St. Mary’s Mission and boarding school in Odanah, Wisconsin. The school closed in 1969, and McKenzie recognized that she knew almost nothing about it. “I felt like that part of the history book was closed,” she said.

Searching the web after that telephone call, she found an article called “Indian Boarding Schools,” written by Native American journalist Mary Annette Pember. That article was life changing for her. She felt that the Holy Spirit had led her to a moment of recognition that “went deep. The big part of our work right now is confronting the truth. This part of the process is probably the hardest.”

Most of the sisters of the order were unaware of this history, and when McKenzie first brought it up with her community, “sisters were very disturbed by it in different ways,” she said. “It was unsettling, painful.” Some were frankly disbelieving. “We did great work there, didn’t we?” asked some. Learning about how damaging the boarding school experience was for many—and about both Native American history and the church’s complicity in colonialism—“kind of disrupted the story. You can’t escape it.”

McKenzie reached out to NABS and asked how they could connect. FSPA has since opened up its records to NABS’s work, as part of a movement to create a national database of former students and their whereabouts. Right now, said McKenzie, the sisters are working with local historic preservation offices and the bishop’s office in the Diocese of Superior, “trying to find out where the children are who have disappeared, the ones we can’t account for in our records.” Further efforts include opening up their archives to the Bad River Band tribal preservation historian, repatriating objects that belong to the Chippewa, and hosting journalist Pember as she explored their archives, said FSPA communications director Jane Comeau.

Even the most well-meaning researchers come up against the central difficulty that religious institutions are reluctant to confront the cruelty of the past. And even in the most meticulously kept records, the dead cannot speak. As the sisters attempt to be more transparent and accountable to a history that they are only now viewing in a different light, said McKenzie, they are facing the fact that “the government and the church’s complicity in the policy of erasure was pretty effective.” In processing this new way of looking at their history, the sisters have expressed a range of reactions, including defensiveness, determination to atone for past sins, and ambivalence about their role. Some are determined to move forward fast, and others are suggesting that they don’t know the whole story.

That range of emotions mirrors those in other religious communities, said McKenzie. “We’re all in the same boat. There’s no excuse not to listen to these stories. Other congregations need to do it; the church needs to do it.”

A lawyer and member of the Turtle Mountain Band of Chippewa Indians, Jerilyn DeCoteau has been an active participant in conversations with Christian groups. But she is pessimistic about whether the legacy of more than a millennium of Christian worldview can be overcome. The assumption that White Christian culture was superior was baked into every aspect of the life of these schools, she said. Those who ran the schools didn’t see the ways some of their core doctrines disregarded the rights of Indigenous people. “Christians,” she said, “are supposed to spread the word of God, their god. Proselytizing is basic to their belief, their faith. . . . This is a fundamental problem for Catholics’ ability or willingness to respect other people’s beliefs. I don’t see how they can be true to their faith and allow and respect other people. The two are not compatible.”

Ultimately the work of Indigenous communities and their tribal councils will determine the outcomes, which will likely vary.

Research done by the NABS and the federal government initiative now unfolding under Haaland’s leadership will illuminate the bigger picture of what happened at these boarding schools, said DeCoteau. Then it will be up to tribal communities and individual survivors to determine what will bring healing to their communities. That could include Indigenous language programs, revitalization projects, and welcoming home the bodies of students who died and were buried on institutional grounds, she said. (In some cases, this is happening already.) “It just has to unfold now.”

No Native American individual or family has been left untouched by the erasure of family, ceremony, language, and community, said Torres. Given the scale of generational trauma, the process of accountability and healing may take generations as well.

“There needs to be a commitment from our society to be able to restore that which was taken,” he said.