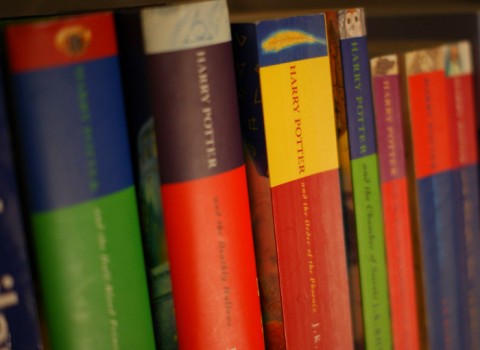

Harry Potter, holy writ

People read J. K. Rowling’s books as if they were scripture. What if they were?

A few years ago I wrote here about my student Vanessa Zoltan and her experiment with reading Jane Eyre as if it were a sacred text. She read and reread each chapter, prayed its prayers, wrestled with its difficulties. She often felt transformed by her reading, for once she began to treat Jane Eyre as sacred, she found herself approaching other parts of her life—relationships, conversations, encounters with strangers—as if they were also sacred.

There were times when she felt betrayed by the novel, as when the full horror of the imprisonment and death of the West Indian “madwoman in the attic,” Bertha Rochester, impressed itself on her through repeated reading. Loving Jane as she did, Vanessa was surprised to find the sacred heart of the novel in Bertha, a character who upended Vanessa’s expectations about her project, a character who made her feel not only challenged, but also read and interpreted. A sacred text, Vanessa learned, is not a perfect text, free from contradictions and outrages. A sacred text is a generative text, one that keeps reading and changing us.

Sacred texts also become sacred in community, and so Vanessa gathered a small group of Jane Eyre lovers and invited them into her practice, teaching them what she had learned. Fellow M.Div. student Casper ter Kuile joined in. Wouldn’t it be fun, he teased, to try this with a book that people actually read?