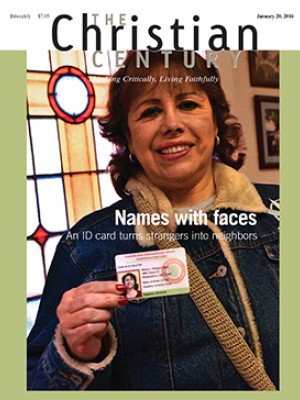

Names with faces: An ID card turns strangers into neighbors

I’m sitting at the back of a church hall full of people, and the only people facing me are the ones at the podium up front and a handful of toddlers perched on laps. One little girl has pigtails sticking straight up from her head; she smiles at me when we make eye contact.

The people gathered this morning are mostly immigrants, many undocumented. They are here to get a photo ID card distributed by FaithAction International House, an organization that serves and advocates for immigrants in Greensboro, North Carolina, where I live. FaithAction ID cards are recognized by our police department and by other local organizations and businesses. They provide a much-needed means of identification for people who aren’t able to access government-issued IDs.

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

I could get a FaithAction ID—everyone is eligible—but I don’t need one. I have a long line of documents authenticating my identification, going back to the day I was born. I’m rarely concerned about proving who I am. That’s not true for many people in this room, where the little girl has now escaped her mother’s reach and is wandering in the aisle.

When the speakers at the podium are done, the people in front of me remain, waiting for their turn to have their picture taken. I slip down the side toward the front and linger for a minute in the doorway, looking back at the faces in the crowded room. Each face tells a story.

On a sunny fall morning, I wait for David Fraccaro in the lobby of FaithAction’s building, a converted house in one of the oldest neighborhoods in Greensboro. The FaithAction executive director is an ordained minister in the United Church of Christ, and I run into him often at local clergy gatherings. As I take a seat in what was probably once the dining room, I see a collection of toys in the corner, an effort to make this a welcoming place for people who aren’t often welcomed and who often have to wait. A bulletin board is crowded with multilingual flyers for community events, along with one for FaithAction’s annual fund-raising event—not a dinner gala but a musical revue featuring artists, including Fraccaro himself.

The predominant narrative about immigration in our country, Fraccaro explains when we sit down to talk, is that immigrants are a problem to be solved, or helpless and in need of saving. He leans forward, underscoring his point; his passion for this work shows. “There isn’t a narrative that tells that [an immigrant] is an individual, a human person, with a story of his or her own.” That’s the story FaithAction wants to tell.

Many of the immigrants served by FaithAction are living in mixed-status families: while some members of the household have proper documentation, others don’t. This complicates access to everything from education to health care to social services. These families live with the constant threat of deportation, are usually near or below the poverty line, and are often learning a new language even as they navigate an unfamiliar culture.

The ID program is a response to this lack of documentation. The initiative grew out of a series of community dialogues between law enforcement and the immigrant community, organized by FaithAction and hosted by a number of local faith communities.

FaithAction staff and volunteers had noticed a disturbing trend among the immigrants who came to them for help: they were afraid to go to the police. Domestic violence victims, sorely in need of protection and assistance, were particularly fearful. “You can’t talk to them,” Fraccaro reports hearing from one client. “They’re like sharks out to get us.”

So FaithAction did what they do best: they brought people together to talk about it. First it was faith leaders, particularly from congregations with deep connections to the immigrant community. Then these faith leaders had conversations with police officers. This led in turn to a series of public dialogues held in congregations, often after a regular weekly service, at which police officers and immigrants were encouraged to talk directly to one another, to share stories about their experiences, and to discuss their fears and concerns. Over a year, FaithAction helped host six well-attended dialogue sessions.

Through these open conversations, misconceptions were cleared up. Immigrants learned that the police aren’t in charge of issuing drivers licenses and that they don’t work for Immigration and Customs Enforcement. Police officers learned to use language like residents instead of citizens. Fraccaro tells me that by the end of the dialogue series, the consistent message from officers was this: We are not here to enforce federal immigration law. We are here to serve and protect all residents. We need your help.

Slowly the narrative began to change. Immigrants stopped seeing police as sharks out to get them. Officers began to understand the fear immigrants live with. Officers listened to people’s stories and then began to share their own: some had immigrated themselves or had immigrants in their families. One officer told the gathered group that his mother had walked through the desert to get to the United States. Officers developed what Fraccaro calls a “professional vulnerability” that has increased their authority by evoking the respect of the people they serve.

“You could see it around the room,” he tells me, thinking back to those dialogues, now several years ago. “It was the power of the Holy Spirit, in that sacred space.” The police listened to the people, and the people felt safe.

|

There was one consistent theme that arose from these dialogues. The lack of identifying documentation wasn’t just a problem for the immigrants; it was a problem for the police, too. Officers who encountered someone without any ID had to leave the street, go into the precinct, and file a report. What would have been a routine traffic stop turned into a whole afternoon of paperwork, and it took the officer away from patrolling the streets.

What if, they wondered together, there was a way to provide undocumented immigrants with an ID card that the police could recognize and trust?

A private foundation donated the start-up costs of the ID program, including some basic equipment such as a camera and a printer. The first ID drive, held at one of the congregations that had hosted a dialogue session, was packed with 250 people.

From early on, the program had the support of the chief of police and city leaders. FaithAction staff and volunteers, along with law enforcement leadership, trained police officers to recognize and accept the FaithAction ID as a valid form of ID. At first, the ID cards were recognized only by the police. Soon, it became clear that people needed identification for all kinds of things. The success of the program within the police department convinced city leaders to accept the IDs as proof of residency to turn on water or to register kids for school. The library and the parks department began to recognize the ID as well.

The card also became much more than just a means of identification. FaithAction seeks to build stronger communities, not just provide assistance. So it arranged for ID cardholders to be eligible for discounts at certain local shops, museums, restaurants, even the community theater. Fraccaro says he encourages people who have access to other IDs to get the FaithAction card anyway and to take advantage of the discounts. It encourages the integration of places shared by the entire community, he explains.

On my way out after talking to Fraccaro, I stopped to chat for a minute with Dulce Ortiz, a former FaithAction client and now a staff member. She has used her ID to access health services for her family; it also served as supporting documentation so she could get her Mexican passport. She often uses her card for a discount at the local food co-op around the corner. (“We go there a lot for lunch,” she says with a grin.) When Ortiz tells me she’s used her card to get discounted admission to the Greensboro Children’s Museum, I think of the many afternoons I’ve spent there with my own children, and I can see what Fraccaro means when he talks about shared community spaces.

The ID card doesn’t just prove identity; it’s a way of turning strangers into neighbors. “We wouldn’t have gotten this partnership if we had named and shamed the police department,” Fraccaro says. “There’s a place for speaking truth to power”—he raises his fist as he says this—but this wasn’t it. The partnership was built by carefully tending relationships, and by the participation of faith communities that opened up their sacred space and made it possible for a dialogue to begin.

Since the ID program began in 2013, FaithAction has issued more than 3,000 IDs to people in Greensboro and neighboring Alamance County. The group has fielded calls from law enforcement agencies across the state and the country, and it hopes to inspire other communities to establish similar programs. Fraccaro notes that New York City instituted an immigrant ID program last year. “When was the last time Greensboro was ahead of New York on something?” he asks with a smile.

At an ID drive in August at the church across the street from the FaithAction house, Fraccaro welcomes people and gives a brief history of the program. I count 100 people, maybe more, seated in chairs in the church social hall. I’d pictured a line out the door, and I’m struck by the hospitality of simply having a place to sit in while we wait. Fraccaro pauses every few sentences for someone to translate into Spanish. “This means trust,” he says, holding up his own ID card, which he pulls out of his wallet. “It means we’re all welcome here.”

Along with the FaithAction staff and the clients here for IDs, there are a dozen or so representatives from community agencies, many of whom have set up booths at the back of the room for people to gather information or make a connection. Fraccaro calls them up to the front, and they each introduce themselves and their organization. Everything is translated, and many speakers start with the Spanish and translate for themselves. I’m particularly impressed by those who are clearly not fluent but have learned enough to convey their message; it’s a sign of respect for the people gathered here that both inspires and convicts me.

There are representatives from the school system and a variety of city agencies, as well as other local community groups. A firefighter stands up to remind people to check the batteries in their smoke alarms and offers to deliver new batteries if necessary. Making eye contact with several parents who are corralling young kids, he adds, “We’ll deliver them in our big red truck.”

It’s remarkable to see the number of people—city employees, law enforcement, community agency representatives—standing in front of this group of immigrants, many of whom may not have any documentation regarding their legal right to be here. Everyone is offering to help.

The ID program affirms and assumes the basic goodness of people. That’s what makes it so powerful: the assumption that each individual has an identity—a name, a face, a story, and inherent worth—and that we can work together to build a stronger community. In Greensboro, as in the nation, racial-ethnic diversity has increased dramatically over the past generation. “Will we fear one another as strangers?” asks Fraccaro. “Or embrace one another as neighbors?”

At the drive, Fraccaro is careful to explain what the card does and does not do, and each recipient has to sign a contract. “This is not a license to drive,” he says. It will not impact your immigration status or help you avoid prosecution if you break the law. It’s accepted only by the police department, not the sheriff’s office or the highway patrol.

Along with ten dollars, clients have to have some kind of photo ID to get the ID card. This at first seems counterintuitive to me—aren’t these people who have no documentation? But it makes sense: the program is built on trust, and FaithAction has to assure the police department and others who accept the card that the ID is accurate. An expired driver’s license, a passport, even an ID from another country will do, along with proof of address. Fraccaro gets stern at this point in his talk: “If anyone here is planning to use false information today, don’t do it,” he says. “It won’t do you any good, and it will hurt things for everybody else.”

A police officer comes to the microphone next and speaks primarily in Spanish. I’m lost, my rusty high school Spanish inadequate to the task. But I can tell from his body language, his smile, and the crowd’s reaction that this is a friendly exchange. There is laughter and gentle bantering back and forth. I learned later that this is one of the officers who was involved in the original dialogue series, and I can see how significant this has been in helping people understand that the police are here to help. De dónde eres? he asks at one point, and I understand that one. People raise their hands and answer: Cameroon, Honduras, Niger, Venezuela. They seem eager to tell him where they’re from, to offer up the name of their home country into this room full of people who have come from all over the world.

Clients were given a number when they came in; after the introductions, they’re called up a group at a time. Still there’s no line. They can sit while they wait or listen to the officer as he continues his dialogue-turned-stand-up-routine in Spanish or visit one of the several agency representatives.

One by one, the clients take a seat on the stage, the light shining on them. It’s clear that this card is more than a document that will save them some hassle with the police. As they have their picture taken, they are recognized as unique individuals—not just one big mass of people, not just a problem to be dealt with. A tall man with a cane carefully takes his cap off before the picture is snapped. A woman in a bright green dress sets her handbag next to her chair as she sits down. A mother feeds applesauce to her toddler as they wait. All of us slowly become neighbors.

When Fraccaro and I spoke in mid-September, I asked him what resistance the ID program had encountered. He gave a halfhearted grimace and a shrug—there’s always push back when you do the kind of work he does. There had been a few attempts to pass laws restricting the use of such IDs, but so far they’d died in committee.

That changed a few weeks later, when the North Carolina legislature went into overdrive in the last days of its session, pushing several bills through with little opportunity for public debate. House Bill 318, otherwise known as the Protect North Carolina Workers Act, passed easily. The bill seems designed to target undocumented immigrants. In addition to cutting food assistance for the unemployed, expanding the E-Verify program for employers, and banning sanctuary cities, HB318 limits the kinds of ID cards that government officials can accept. “It has little to do with protecting workers,” Fraccaro told me later, exasperated.

A number of law enforcement officials spoke out against the bill, and a late amendment removed a provision that would have prevented police from accepting IDs such as FaithAction’s. The Greensboro City Council spoke out against HB318 as well, voting overwhelmingly to oppose it; this did little to sway Governor Pat McCrory, who made a special trip to Greensboro to sign the bill into law. Under the new law, the city will no longer be able to accept the card as documentation for utilities or other services.

Fraccaro says this won’t stop FaithAction from continuing its work. Two days after the governor signed the bill, the church across the street from the FaithAction house is again filled with people eager to step in front of a camera and get an ID card. There are twice as many people this time, maybe more. Many have come from neighboring cities; for some, the new law means that consular IDs from their home countries are no longer valid, and they’re hoping their communities will begin accepting the FaithAction card.

Representatives from the police department and community organizations are here again too, and their words are even more poignant this time. A uniformed police officer and a city council member each say to the crowd that despite HB318, we wish you well, and we’re here to support you—because you are a part of our community. A representative from the library chooses her words carefully; it’s not entirely clear whether the new law views librarians as government officials. “Our mission,” she says, “is to share information, and we will continue to do so.” I fall a little more in love with libraries right then.

But it is a police captain who blows me away. He assures the crowd that the police will continue to accept the FaithAction ID. He takes the microphone and says, in no uncertain terms, “The Greensboro Police Department does not care about your immigration status.” I can’t quite imagine what this statement must sound like to someone who lives in fear of deportation.

Fraccaro likes to say that an ID card is just a piece of plastic until a community gives it value. At least here, this morning, our community has.