Innovation’s midwives

From atop its hillside setting, San Francisco Theological Seminary looks out over a stunning landscape of cresting hills and ancient trees. The school is located north of San Francisco, in San Anselmo, a city that somehow manages to balance “laid-back” and “tony.” The seminary has always lured students with its stunning geography. Now it’s also using the area’s rich resources—art, technology, and business—to create the Center for Innovation in Ministry.

Across the country, seminary graduates often complain that their degrees prepared them for congregations that existed 50 years ago and not for the church that we are birthing now. New pastors can feel unprepared for the richly innovative time in which they’re living.

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

Some graduates become unhinged. While they have learned to preach sermons from a pulpit, they may not be ready for the conversational expectations of social media culture. They meet the ordination requirements of Boomer-led denominations, yet when they enter the church they quickly realize that they need to attract younger generations. They’ve been trained to become full-time pastors but discover they need to supplement their incomes and help the church to have reasonable expectations of their time. They can preside over a funeral but know little about faithfully closing a congregation or starting a new one.

SFTS understands that the church is in the midst of this transformation, so it has launched the Center for Innovation in Ministry to help meet the emerging challenges of the church and to welcome change to its institutional culture.

Sherri Hausser, program manager for the center, explained that they are building a research and development laboratory in the midst of the seminary to create space for the birth of new ministries and to connect unlikely partners for the good of the church and the world.

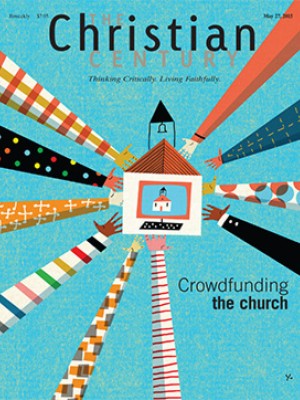

Hausser said the center is designed to be a midwife. With its feet anchored on institutional ground, the center will have its arms outstretched to embrace the new. “As structures fall away, what the church needs to remember is that we have the central story. We forget that new forms are being born,” Hausser said. “Many things want to be birthed. It’s our job to hold that space.” This midwife process takes place in the academic spheres of seminary classrooms, in professors’ writings, and in research libraries, but the center does not just want a think tank; it wants a “think, do, and be” tank.

For instance, the center hosts religious writers like Phyllis Tickle to talk about the ancient future church. But coordinators have also invited doers, including church planter Bruce Reyes-Chow and game designer Jane McDonigal.

The center leaders have invited the larger church to embrace the process of creating. In a session that I attended, church leaders and students worked with Smallify, a company that creates rapid innovation labs. We learned a speedy process of brainstorming and incubating ministry.

For an upcoming event, the center invited seven artists—preachers, musicians, composers, painters, and potters—who regularly hold workshops for people but never get a chance to collaborate with one another. They will work together behind closed doors for three days, then open the doors and invite the community in for an evening in the theater and a full day of workshops.

The center works to connect people with one another, stimulating conversation between academics, artists, politicians, and practitioners. Leaders understand that in the decades to come some churches will look the same while others will be radically different. The goal is to keep both kinds of communities working and learning together. Hausser sees her job as helping people to bump into each other more. “People think that they’re working alone,” she says, but the center has shown her that the Spirit is moving through a larger work.

I am hopeful for the center and have been watching it take shape for many years. Like many conversations on the future of the church, much of the work feels amorphous, like a lump of clay that is yet to be shaped into an object. Participants ask: “What will the center look like? What does the center have to do with the rest of the seminary? How can we find intersections between practitioners and faculty?”

The nebulous nature of the work does not seem to bother Hausser; she enjoys the tension between innovation and the institution. Her vantage point allows her to see how the Spirit is moving in this moment—through seminaries, the arts, new worshiping communities, businesses, and technology. “God is infinitely creative,” Hausser says. “There are more people working on the greater project than we realize.”