The body in motion

A woman walks into the Sanctuary of the Arts, a dance studio in Oakland, California, and does something that we rarely see in church. Stressed and exhausted, she responds to her internal longing by folding herself up on the floor in the corner of the worship space. She lays motionless throughout the service, because her body needs stillness.

And then something even more rare than that happens: the community appreciates that she honored the wisdom of her body.

About a year and a half ago, Jeffrey Cheifetz, a pastor in the Presbyterian Church (U.S.A.), and Amy Shoemaker, from the Disciples of Christ, decided to start something they had been talking about for years—a dancing church. Shoemaker was trained as a dancer but felt a calling to something beyond performance.

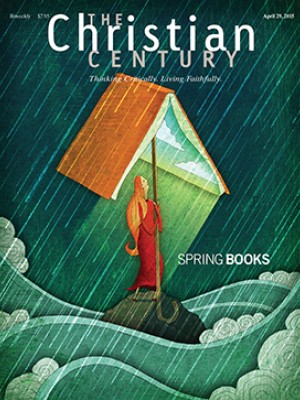

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

After seminary, Shoemaker expanded her focus on dance by teaching people to listen to the wisdom contained in their bodies. When Cheifetz asked her if she would like to start a new church, Shoemaker realized that she could draw on both her theological education and her dance experience.

Shoemaker and Cheifetz started the Sanctuary of the Arts aiming to explore creativity through paint, clay, music, storytelling, and movement. Though the church has traditionally been an important setting for the arts, including choral music, liturgical poetry, oratory, sacred architecture, and iconic painting, many art forms have been left out of worship, particularly when what is expressed is not aesthetically ideal or technically flawless. Sanctuary for the Arts allows for a more expansive inclusion of art.

Sanctuary of the Arts bases its worship service on improvisational movements that can be modified for different abilities and disabilities. The structure of the service is traditional even when the expressions are not.

The service begins with a call to worship, when people shake out their arms, legs, and voices. They bend over and roll up. They become a choir of stretches in order to get the blood flowing.

Then the community joins in an opening song, usually a simple call and response chant, sung a cappella or accompanied by a keyboard or drums. Often the worshipers learn a song that has been created by community members.

At Sanctuary for the Arts, scripture may be explored by comparing different translations. People sometimes read to one another. They put the text in conversation with modern authors like Thich Nhat Hanh and Denise Levertov. Sometimes a visual artist will visit to provide another kind of engagement with scripture.

The service engages texts through movement in various ways. For instance, on one Sunday each person read scripture verses on a piece of paper, meditated on the passage, highlighted phrases, and then circled one word from each phrase. Partners then drew the circled words on each other’s arms or legs with body paint, and then they danced in a circle with the words of scripture.

The response to the Word may take the form of a community prayer. A huge canvas is rolled out on which people can write or draw their prayers. Then Shoemaker uses decoupage glue to place translucent paper on top of the writing. The next time the community gathers, people write their prayers on the new surface. This allows them to see some prayers through the translucent layers, while others become obscured.

Worshipers use their bodies to clarify prayers, dancing on behalf of people, things, and events. They join in communion each time they gather, singing as they eat and drink together.

Cheifetz says Sanctuary for the Arts is made up of an eclectic group of people, diverse in age, ethnicity, sexual orientation, and religious or nonreligious background. It’s “a multifaith community, including some with no faith.”

Shoemaker uses the phrase “embodied wisdom” a lot, and I asked her to clarify what that means. She explained the difference between body data, body knowledge, and body wisdom.

Body data is information about how we feel. For instance, we might feel cold. Body knowledge is the pattern we discern in the collected data. We might feel cold in the mornings. Body wisdom refers to the choices we make that are rooted in the patterns of our experience. This wisdom emerges from listening to and trusting our own information about the body and aligning that with the common good. Body wisdom tells us that we need to grab a jacket in the mornings. Too often, she says, our spiritual lives are cut off from that embodied wisdom, leaving us fragmented.

I nod, because I know that I’m fractured myself. My religious experience remains in my head. Even my art is comfortable there, knocking about in those dark, internal spaces, creating pictures and evoking visions with words. The thought of movement and dance frightens me. I wonder how many people are like me—terrified of physical movement but knowing that they need it.

Cheifetz and Shoemaker remind me that we don’t have experiences separate from our bodies. “Much of our experience of the divine is beyond words,” Shoemaker says. “The arts help us to get to that place.”