Embrace & abandonment: A pastor and a poet talk about God

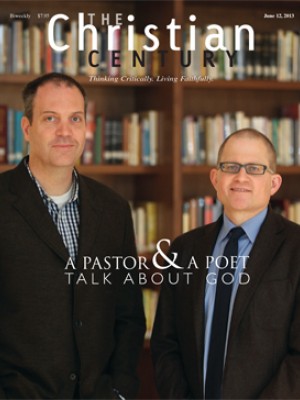

In the past few years the editors have gotten to know Christian Wiman, a poet, and Matt Fitzgerald, a pastor. Both have written for the Century. We recently learned that the two have often met to discuss faith and their different vocations.

Christian Wiman described it to us this way: “About eight years ago I began to meet every Friday afternoon with Matt Fitzgerald, who was the pastor at the church just around the corner from where my wife and I lived. I think that Matt, like anyone whose faith is healthy, actively craved instances in which that faith might be tested. So we argued for an hour every Friday, though that verb is completely wrong for the complex, respectful, difficult interactions we had. Nothing was ever settled. In fact Matt—I can say this now because we’ve become close friends—seemed to me mulishly orthodox at times, just as I seemed to him, I know, either boneheadedly literal when I focused on scripture or woozily mystical when I didn’t. Those conversations have continued and deepened over the years, and Matt and I thought there might be some benefit to sharing some of them.” We agreed.

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

Christian Wiman: Let me begin with a confession: I don’t believe in God. Let me hasten to add—like a drowning man gasping for a breath of air—I have faith.

It’s a semantic distinction with existential consequences. Belief has objects: the Bible is the word of God, Christ died to redeem our sins and rose on the third day, the devil has abandoned the tongues of serpents in favor of talk radio. Faith is intransitive (God is not an object): I live toward God, in hope of God, in dire need of God, but I do not live with God, at least not in the way that I imagine when I read the raptures of mystics, or the certainties of systematic theologians, or even the grounded “orthopraxis” of modern liberal Protestantism. I am drawn to all of these, which is why I mention them, but I stand outside of them too.

I don’t think I’m alone. During the last few years I have spent a good deal of time speaking to audiences around the country about matters of faith. It’s an odd existence at times, since I often find myself in the position of articulating a faith that I don’t fully feel. I think suddenly, piercingly of Dag Hammarskjöld’s remark: “When a 17-year-old speaks of [the meaning of life], he is ridiculous, because he has no idea of what he is talking about. Now, at the age of 47, I am ridiculous because my knowledge of exactly what I am putting down on paper does not stop me from doing so.”

I am 47! I don’t mean to suggest that I am lying in these instances. I am probably never more honest. There is something about speaking one’s faith that releases it (I don’t say “creates” it), gives it form and feeling that otherwise would have remained latent, dormant, unavailable. Faith is like art in this regard. “How can I know what I think until I see what I’ve said?” asked Ezra Pound (I have also heard this attributed to E. M. Forster). Over and over, before audiences both secular and religious, I find myself trying to be true to a faith whose truth is elusive, trying to articulate a peace and presence whose call seems to be absence and anxiety. And over and over I am moved by the number of people, both secular and religious, who respond to this note of crisis.

I’m lonely, then, but not alone. This suggests to me three things. First, the feeling that I am describing is widespread in our culture and cuts across all kinds of spiritual persuasions. Second, faith craves company, craves the catalyzing love of others in order to be faith (Christ is always stronger in our brother’s heart than in our own, as Dietrich Bonhoeffer said). And third, for all that we need these others, for all that we understand that God’s very nature is in relationship, there remains something intractable and insoluble at the center of ourselves, a rip in existence, a loneliness of the soul.

Is the answer mysticism or dogmatism, forgetting or embracing God, oblivion or heaven? Outside of art, which includes and reconciles all of these apparent antinomies, I’m never quite sure what to say. One thing I am pretty sure of, though, is that this loneliness is the key to God, or maybe better to say that God is both the affliction and the antidote. The condition is not nearly as modern as many people think. “Oh, that thou shouldst give dust a tongue / To cry to thee, / And then not hear it crying!” That’s the poet and priest George Herbert, over 400 years ago.

Is the spiritual/existential condition I describe familiar to you, Matt, both in your own life and in the life of culture as you encounter it? And second, if the condition is familiar, what does it mean for your life as a pastor, from the sermons you give to the pastoral care that you offer others?

Matt Fitzgerald: You’re right, we aren’t the first people to experience God as both embrace and abandonment, the slice and the stitches at the exact same time. The paradox is ancient. Jesus embodied it, and he quotes a writer much older than Herbert when he names it: “My God, my God why have you forsaken me?”

I think we expect our experience of God to be positive because God is good. I know that you are exploring what it means to wrestle with him—you’re not asking why you didn’t get the parking spot you needed—but one hopes that relating to a good God would be easy. And I agree, on most days, faith is anything but.

Yet we keep insisting that it ought to be otherwise. Actually, I think that kind of protest, the insistence that faith ought to be unalloyed joy, is worth celebrating. The problem arises when we insist that this is what faith actually is. There is an old hymn that I hate. It claims, “There are sweet, sweet expressions on each face, and I know they feel the presence of the Lord.” I remember singing this stanza one Sunday morning in worship and looking up to see distraught faces and grumpy faces. Yes, there were some sweet expressions. But others were distracted, uncertain, anxious. Who is to say that God wasn’t causing those looks and that self-satisfaction or gluttony weren’t causing the sweet ones?

We are not only at constant risk of projecting “the best” human attributes onto heaven and then mistaking them for the reality of God; we are also guilty of assuming that faith corresponds to a resulting impossible state of happiness.

I think this could be why you’ve evoked such gratitude for articulating a faith that has holes, dissatisfaction and anguish. You are tearing down an idol. It is liberating for people to hear that while faith is like water on parched lips, it is also sheer, unanswered longing. Particularly when the popular conception of Christianity assumes that faith demands certitude and promises cheeriness in return. We need to hear that actual faith is something altogether different. Many years I get a more enthusiastic response to the sermon on doubting Thomas than I do to the Easter sermon.

But Thomas didn’t doubt forever and my job won’t let me sit in the paradox for long, which is not to say that I believe what I preach each Sunday. I laughed out loud when I read that Dag Hammarskjöld quote. I never feel so ridiculous as when the assigned text calls me to proclaim the presence of God on a day when all I know is God’s absence. But I have to proclaim it whether I believe it or not. I don’t think a perpetually doubting preacher would last long, but ultimately the efficacy of my efforts doesn’t ride on the assuredness of my own faith. Augustine answered that question when arguing with the Donatists in the fourth century. And the logic of Martin Luther suggests that the transmission of God’s word is dependent upon grace, not the preacher’s belief. There are days when the best I can do is try to get a better sense of the Jesus I’m longing for. As Karl Barth quotes Paul Althaus, “I do not know whether I believe, but I know the one in whom I believe.”

It took me years to get to gratitude, but I am grateful that ministry calls me to surrender all of this perplexity to the story that reveals Christ. For in that act of submission my own faith gets much more concrete. Jesus says he is a “narrow gate.” I bump my head on the gate almost every time I approach it. I’ve scraped my face it on it. But every time I squeeze through I arrive at a broad and spacious place I could never find on my own.

It sounds as if speaking publicly about your Christianity is causing something similar to happen to you. This makes me wonder if it is your vocation as a poet that leaves you feeling so unsettled. I imagine that in order to articulate the truth in a given poem you have to feel that truth with everything you’ve got. I doubt that Philip Larkin wrote “Aubade” on a day when he was feeling optimistic about the possibility of resurrection. He believed in death wholeheartedly, and his faith in the grave comes shining through every syllable of the poem. Or at least it seems that way to me. Am I right about this? Does poetry call for an assuredness that faith cannot accommodate?

As for pastoral care, whenever I encounter the sort of misery that makes faith complicated I try to point the sufferer toward the cross and God’s own suffering. I once read that “pain stings the faithful twice.” First it hurts, and then we wonder why God allows it. So I use Jürgen Moltmann to urge my parishioners to imagine a completely impassive deity, one who is “only almighty” and nothing more. Moltmann says, “A god who is incapable of suffering cannot be involved. Our pain does not affect him. He cannot be shaken by anything. He cannot weep, for he has no tears. But the one who cannot suffer cannot love either. So the god who cannot suffer is also a loveless god. Is he a god at all? Is he not rather, then, a stone?” We might want a god who could prevent our agony. But the cross suggests that the God we have cries right alongside us. So I try to argue with my parishioners’ pain. I believe that the cross is the truth and that I’ve won the argument every time, but I don’t know if I’ve convinced a single soul.

CW: Oh, you have, my friend, believe me, you have. But I suspect we’re getting at the crux of our different callings. For instance, I would have said that religion calls for an assurance that poetry can’t accommodate. This is precisely why so many modern artists have renounced religion—it seems to require a fidelity to “truth” that precludes the volatile and anarchic experience of making art.

I’m drawing a distinction again between belief (religion) and faith, both because I think it’s a crucial one and because it’s hard for me to think of any great artist as faithless, even when he calls himself an atheist. Take Larkin, for instance, who once wrote that if he could construct a religion (not a faith, which man can’t create), he would make one that was like water, where “any-angled light / Would congregate endlessly.” Even the disturbing, death-obsessed poem “Aubade” manages, by formalizing a genuine despair, to neutralize it. Not permanently, by any means, but the poem is, as Robert Frost defined all poetry, “a momentary stay against confusion.” And the first step to being out of despair is to know concretely what it is.

T. S. Eliot once wrote (of Dante) that it is not the poet’s job to convince us of what he believes, but that he believes. We respond to his or her faith, though we may feel nothing for its object. This is the very opposite of Luther’s formulation, as you suggest, and the life of a poet would seem to be in this sense diametrically opposed to the life of the pastor. “If you do not believe in poetry, you cannot write it,” said Wallace Stevens. This is quite true in my experience. It is also true, though, that a poet, even a great one (perhaps especially a great one), may write only five or ten poems a year. That’s an altogether different order of experience from climbing up into a pulpit to preach every Sunday.

Or is it? I have long thought that there was something heroic about the act of being a pastor in this culture. The ones who have survived both secularism and the church’s own institutional sclerosis, I mean, the ones still preaching from their hearts at 50 and 60 and beyond. Marilynne Robinson’s novel Gilead gives a powerful presence to such a person and is a testament to the enduring power of the gospel message as it has come down in Protestantism. But it is perhaps sadly significant that she felt the story had to be set in the past.

Just the other day I was talking to a pastor in his early sixties, an old-school Barthian who told me, essentially, that the gig was up. When I related my experience of meeting so many spiritually starved people around the country and asked if he found the same to be true in Protestant churches, he laughed as if I’d made a joke. He said that liberal Protestantism was in its death throes, that he almost never encountered anyone who was on fire with faith. He said that modern churches filled a social role, like the Rotary Club or the Lions Club. This is not a cynical man. He’s still deeply engaged in his faith, constantly seeking out genuine encounters with other believers. These ideas weren’t novel to me, of course, but still I came away disheartened, mostly because—despite his laughter—it was so evident that he was disheartened.

Perhaps both of us should admit that the times are different. Like you, I cling to Christ’s words on the cross, however unlikely they are (that a tortured person would quote a poem, I mean). I want to see my own agony reflected in George Herbert’s lines. But things have changed. Herbert agonized over the fact—he felt it as a fact—that God was silent, not that he was a fiction. It is estimated that at the turn of the 18th century there were maybe two dozen people in America who did not believe in God (I get this from Roger Lundin’s book Emily Dickinson and the Art of Belief). Sixty-five years later, after the Civil War and after Darwin seemed to have destroyed both literal scripture and natural theology, Emily Dickinson could write:

Those—dying then,

Knew where they went—

They went to God’s Right Hand—

That Hand is amputated now

And God cannot be found—

A century and several wars later and where are we? Well, you mentioned Larkin. In his other great masterpiece, “Church Going,” a speaker wandering through one of the unkempt and empty churches in England wonders what happens “when even disbelief is gone.” Despair is one answer, though it often doesn’t even know itself as such. Baffled joy is another, which the poem also implies. Zadie Smith wrote recently in the New York Review of Books about the rarity of real joy and how one almost doesn’t want to have it because it so annihilates one’s pleasant everyday existence (Jan. 10). When I showed my wife the essay she said, “The reason she is baffled by her joy is that she will not let herself recognize the element of eternity in it, and so it burns her up.” A smart woman, my wife, who has brought me much joy.

In my experience every church nods to doubt but has little to say to despair. Churches speak of joy but make no room for its expression. Despair doesn’t even rise to the level of doubt. Joy probably can’t be accommodated by services so predictable that even the leaders have stopped paying attention. Despair is Christ on the cross. Joy is the Holy Spirit, disfiguring every form that purports to know God.

What might this look like? Probably it would look different all the time. If a preacher found herself filled with the void of God on a day when she was meant to praise God’s presence, why not just admit that? Why not throw away the sermon and spend that time on focused prayer, or poetry, or simply sitting in silence like Quakers? (“I used to think I wrote because there was something I wanted to say . . . but I know now I continue to write because I have not yet heard what I have been listening to,” writes the contemporary poet Mary Ruefle.) Perhaps what I’m asking is this: Is it more important to impress upon people the truth claims of Christianity or the living spirit of Christ?

MF: Don’t worry about the old Barthian! He wouldn’t be one if he didn’t find some pleasure in decrying the liberal mainline’s demise (while standing in its pulpit). Not that he’s wrong. I do think, though, that the true vitality of church is often hidden, or at least it isn’t displayed clearly on Sunday morning. The joy and despair you’re looking for tend to surface behind the scenes. Rowan Williams says that Christ “comes in stillness. He comes in dependency, even in weakness.” It is hard to fit such qualities in between the choir’s anthem and the preacher’s attempts at eloquence. But worship can prepare us for them.

Six months ago I was in a parishioner’s kitchen an hour or so after he died. His wife was in the sitting room with his body. Their teenaged daughter, a church friend and I were at the kitchen table. We tried to speak comfort to one another, but we’d run out of things to say. We sat in silence. To me it felt like we were waiting. But waiting for what? The funeral home was due to take away the body, but that would only make the pain worse.

Then the doorbell rang and a plumber stepped in. An hour earlier the hospice nurse had followed protocol and flushed all of the dead man’s medications down the drain. This broke the toilet. The plumber knew none of this. He just walked in to raw grief, a pastor out of words, a reeling family and the recently deceased right there in the living room. He could have run straight to the bathroom. But he didn’t.

He shook my hand, looked the teenaged daughter straight in the eyes and told the grieving widow that he knew what a good man her husband was. As he made his rounds something in the room turned. For a moment the pain broke and became something else. Or at least the pain was met by a power that promised it would not last forever. Grace comes in the most unlikely guise. Christ comes when we least expect him.

This scene took place toward the end of Advent, when the widow, her daughter, their friend and I had been in worship singing “O Come, O Come Emmanuel.” Those Sunday mornings weren’t remarkable, and during them my own religious mood wasn’t necessarily one of anticipation. But practicing anticipation on Sunday morning taught us to expect God to arrive “like a thief in the night.” Or a plumber at a deathbed.

To answer your question, I don’t think we can receive or even see the living spirit of Christ if the church hasn’t impressed the truth claims of Christianity upon us. In my experience such formation has to come first. Without it the object of our longing is “the ultimate vagueness,” as Stanley Hauerwas says. This is, of course, ultimately unsatisfying, like Zadie Smith’s momentarily intoxicating but ultimately baffling experience of joy.

This is one of the reasons I don’t want to tie my Sunday morning efforts directly to my own spirituality. If I did, worship wouldn’t “look different all the time.” It would look the same. It would look like me. Far better to follow the twists, turns and contradictory beauty of scripture. Moreover, the preacher who submits to scripture might find her or his words revealing God, while a reflection on my own religious feelings reveals nothing but my own religious feelings. God’s word comes “from above, not below!” as Barth is always thundering. I can’t dredge it up from within myself. The only thing inside of me is me. And while I’m as egotistical as the next talker who wants to wear a fancy robe and speak to 400 people at a time, I’ve learned the hard way that people don’t come to church to hear my self-excavation.

This could be why preaching is easier than poetry, or at least why preachers can be more prolific than poets. Armed with the Bible, a set of commentaries, a good work ethic and enough time to write, the average preacher can produce a decent sermon every week. Whether God shows up in the delivery is up to God, but the product should be passable. Or at least it will do its job, keep the story alive and point people toward the cross. Meanwhile, a poet has neither the content of scripture to draw upon nor the object of Christ to point toward. What do you have? And where does it come from? I don’t envy your calling.

You note the drastic decline of American faithfulness. I agree. The times are different. The church is different. But I don’t know if it is any worse. I am certainly not the first person to float this thesis, but there could be a blessing in our empty pews. The mainline has begun to evangelize. To be honest, this isn’t because we believe people need Jesus. It’s because we don’t want our churches to die! But in the churches I’ve served, some people come as a result of this work. Not because there is any cultural pressure to join us (quite the opposite) but because the visitors are aimless or desperate or grateful. In other words, they come because they need Jesus. This is going to change us.

The result could be an intense faith, one that is stronger, more potent. If the diluted liberalism I grew up on is a big glass of orange juice mixed with tap water, perhaps the future mainline will be a spoonful of frozen concentrate straight from the can. Maybe we’ll set the world’s teeth on edge or jar it with some ecclesiastical brain freeze. Perhaps we will become strange.

You have made a distinction between faith and belief in God. As you suggest, all great artists have faith. Bad artists also have it. Everyone does. You know Paul Tillich’s definition of faith as an expression of one’s “ultimate concern.” Everybody either learns or is born with an orientation toward some larger, wondrous other. For me (and this might sound unbearably sanctimonious) the important thing isn’t that longing, but its object. Which is to say that the important thing about Christianity isn’t our belief. The important thing is the God that we believe in. Christianity says that God loves us so deeply that he collapsed the distinction between earth and heaven, assumed our “common lot” and came to be with us. We are self-centered creatures, and therefore we spend a lot of time considering what God’s self-emptying means for us or does to us. The better course would be to simply respond, to reorient ourselves toward the one who loves us. To try to get to know God better.

Perhaps the “success” of American Christianity has dissuaded some people from doing this. When Christianity is everywhere it loses its pungency. Skeptics might suspect that our God isn’t much more interesting than the bland and seemingly universal response he has engendered. If this is true, I can see why artists would stay away. All one need do is compare a good secular rock song to its Christian variant to appreciate the death blow that contemporary piety can inflict on art. But perhaps the church’s increasing marginalization, the growing sense that anyone who looks for meaning in a crucified, “marginal Jew,” must have something wrong with her, could cause some poets to take a second look? I would love for this to happen. And I would love to listen to what takes place when what you refer to as the “volatile and anarchic” voice of art surrenders, or at least attunes itself, to the even wilder freedom of God.