Globalization circa 1578

I have always been fascinated by history’s byways and by startling encounters between peoples and cultures that we think of as totally separate from each other. Apart from challenging familiar assumptions, such moments make us contemplate the alternative worlds that might have emerged if matters had worked out slightly differently. In extreme cases, they force us to rethink our history altogether.

One of these truly odd intersections occurred in January 1614, when a strange-looking ship pulled into Acapulco, then the thriving imperial port of the Spanish-ruled realm of Mexico. The ship was a Japanese copy of a Spanish galleon, built by the lord of the Japanese city of Sendai in order to carry a mission to European powers and particularly to the Vatican.

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

As this last fact suggests, the mission operated in the strongly Catholic environment of the Pacific world of its time. A Spanish friar had supervised the construction of the ship, the San Juan Bautista (John the Baptist), and its captain, Hasekura Tsunenaga, was a Christian convert. Apart from seeking trade links with Europe, the lord of Sendai wanted to announce that he was happily open to receiving Christian evangelists: send us as many of the padres as you like! And that is why, in the age of Shakespeare, Japanese samurai were passing through Acapulco and Veracruz en route to Rome.

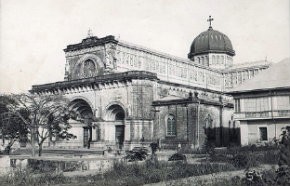

However strange the story may seem in retrospect, it was highly characteristic of this first great age of true globalization. Throughout history, various so-called world empires have arisen, but none really deserved the title. Whether Macedonian, Roman, Arab or Mongol, each regime in its day carved out a vast territory in Eurasia, but none really achieved a global, transoceanic scale. That distinction was left to the Spanish of the Counter-Reformation, who were driven to span the globe by the twin motives of gold and the glory of the Catholic Church. The once-daunting Pacific became a highway, not a barrier, and Christian missionaries led the way. If a single moment symbolizes the unification of the continents, it might be the creation in 1578 of the Philippine diocese of Manila—as a suffragan see of Mexico City!

For a century after that date, the trade route from Manila to Acapulco represented the central artery of European imperial power, as Mexican silver was traded for Asian spices. The route was the world’s most important axis of missionary expansion. By 1614, Spanish and Portuguese Catholics seemed set to convert much of their new Pacific empire. Beyond the Philippines, Jesuit priests were highly regarded at the Chinese court and were winning converts among the ambitious warlords and aristocrats of southern Japan. When the Japanese commander Toyotomi Hideyoshi invaded Korea in the 1590s, captain Hasekura was one of his faithful Catholic followers, who created the first lasting Christian presence in that peninsula.

As a result of these efforts, the Vatican became the unquestionable pioneer of a truly global diplomacy, with departments handling affairs in North and South America, in Africa and in the dazzlingly wealthy empires of East and South Asia. For a few decades, any objective assessment of the Christian world would judge the Catholic world to be vastly more important than those irrelevant Protestants clinging stubbornly to their bare lands in Northern Europe. Clearly, the future belonged to papal Rome and to a worldwide spiritual empire vaster than anything that pagan Rome had ever imagined.

Of course, it was not to be. Even as the San Juan Bautista was reaching Mexico, Japanese authorities back home were beginning a savage crackdown on Christianity, which would destroy the nascent church. While open to the faith, Japan’s rulers had no wish to end up as a submissive Spanish colony like the Philippines. In China and India, meanwhile, once-promising Catholic communities would be devastated by prolonged battles over inculturation and the use of native languages and concepts in the liturgy and in Bible translation. By 1700, the Catholic dream in Asia was fading fast, to the point that it features little if at all in later Protestant narratives of Christian expansion.

But we might still ask if those Catholic enterprises failed as completely as we might tend to think. Yes, Japan was wholly lost, but other parts of the old Iberian empires remained bastions of the Catholic Church. Today, the three countries claiming the largest Catholic populations—Brazil, Mexico and the Philippines—all trace their faith to those early imperial ventures. And if the old missions to other nations failed in their day, they would bear fruit in later centuries. South Korea today has a flourishing Christian presence, and China probably has more active Christians than any European nation. In the long view, perhaps those visionary Christians of 1614 did not fall too far short of what they hoped to achieve.