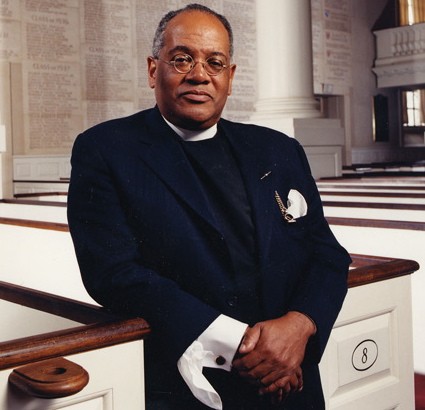

Harvard's preacher: Peter J. Gomes, 1942–2011

The guest preacher opened his sermon with a rather long explication of Augustine's contrast between blessings and consolations. It was probably the first time most of the listeners at Duke Chapel had heard of The City of God. The preacher then reflected on how he had grown to appreciate the blessing of human sexuality. He was reminded of a story about Queen Victoria, who on the night before her wedding supposedly asked her mother how to handle the challenge of marital relations. "My dear, just close your eyes, lie back, and think of England," reported the preacher.

Even the Duke football team—which, since it was "Football Sunday," was packed unwillingly into the front pews—listened intently at this point.

"Young men," said the preacher, looking down on the football players, "Enjoy the gift of sexuality. True, it can make you miserable; but it can also bring you great joy. Don't think that you invented this particular pleasure—surely even you have read the Book of Genesis."