Development woes: Shame and blame in the global economy

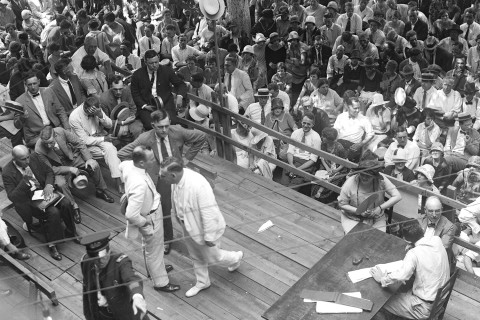

The protesters who came to Washington, D.C., in April to rally against the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund prophetically denounced global inequities and defended the cause of the poor. The fact that so much of the world is excluded from the benefits of the global economy is indeed “shameful and unacceptable,” to cite the words of United Nations Secretary General Kofi Annan in a speech to the world’s financial leaders.

The protesters in the streets of Washington did not hesitate to point out where they think the burden of that shame lies—with the Bank and the IMF, along with the World Trade Organization. According to the protesters, these institutions control the world’s economy and resources for the benefit of corporations and the wealthy.

In focusing on the sins of the Bank and IMF, however, the protesters avoided talking about what remains a fundamental, unavoidable challenge: creating the conditions for sustained economic growth in poor countries. Global inequities are not only a matter of rich people ripping off poor people. Daniel Finn of St. John’s University in Minnesota, who has done some of the most careful theological reflection on the global economy, notes that whatever injustices exist, people are poor largely because they lack the means and resources to be productive workers in the (increasingly global) market. For that reason, poor countries, besides needing to improve their education and health systems, need access to the world market, a fair and efficient government, and a stable economy that can attract capital investors. These latter conditions are, of course, precisely what the IMF and World Bank seek to create.

The IMF has been soundly criticized for, among other things, its “structural adjustment policies” which require poor nations, before receiving financial assistance, to reduce their deficits and cut government spending. In such cases, poor countries often end up slashing spending on health, education and welfare, thereby hurting the poorest of the poor and further undermining conditions for economic growth.

But it’s often the political leaders in developing countries who prefer to cut social spending rather than curtail the government’s corruption or military adventures. And they know that the IMF can always be blamed for the ensuing hardships. Zimbabwe, now sliding toward chaos under President Robert Mugabe, is a discouraging case in point. For years Mugabe’s inefficient, corrupt governance and his resistance to political reform have discouraged international donors and investors.

Intense public scrutiny of the World Bank and the IMF is healthy for those organizations and the people they seek to help. Such scrutiny should also lead to a greater understanding of the complex task they seek to perform.