The wilderness of a rural ministry circuit

I’m now a half-time “missional coach” to a six-church parish. I have many questions.

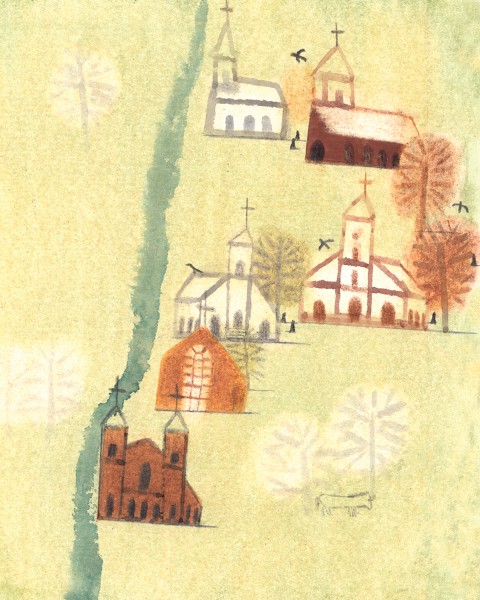

(Illustration by Laura Carlin)

When the bishop first broached the idea of my serving as a “missional coach” with a six-church parish in upstate New York, his expectations didn’t sound high. His assistant promised that if it wasn’t working out, I could give them a month’s notice. I drew a line on a map connecting the six different villages. It traced a question mark, which is perfect because all I have are questions.

At the first parish board meeting I attended, the bishop talked about how great I am. I definitely do not feel great. I can only offer ordinary things: relationship building, small groups, peeling carrots with the kitchen ladies, Bible study, Sunday worship. With only 20 hours a week, there’s hardly time for more.

Twice a month, I lead worship and preach at two of the churches. The schedule requires a mad dash from one to the next—no time to greet people after the first service before I get in the car, still wearing my vestments. And after decades of urban ministry, all this driving is new for me. It takes me an hour to get to any of the churches. But the Hudson Valley scenery is beautiful, and I try to get an idea of the economy as I drive by—farms, guns, a Wonder Bread outlet, construction materials. The largest buildings I’ve passed are a state prison and two Amazon warehouses.