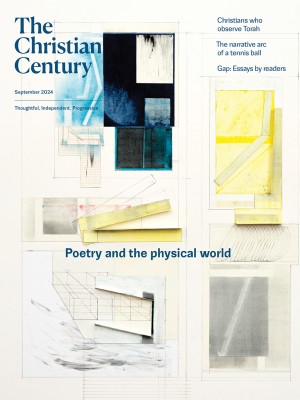

(Illustration by Nicholas Blechman)

The long, hot days of August are mostly behind us now, and here in Chicago we can expect another month or so of time in the garden before the first frost hits. I moved into a house—with a yard!—two summers ago, but the first summer was spent in a post-move exhausted haze, and last summer was spent on the road, so other than a few scraggy, half-hearted tomatoes, the garden part of it lay neglected.

I grew up in a house with a delineated vegetable garden and a compost pile we would rake leaves into, and I remember planting and picking veggies, cosmos and sunflowers higher than my head, sweet peas and beans vining up a trellis. Then we moved to Texas (forbiddingly hot), and I moved to New York (no outdoor space), Boston (more broken glass and rocks than usable space), and an apartment in Chicago (enough light for a houseplant garden, but no outdoor space). So now, this house and this summer represent the first time since childhood when I can see a full growing season out and tend to it myself. I’m not really a rookie, but I also, in a lot of ways, don’t really know what I’m doing.

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

The early days of putting in a garden are both hard work and heady—you’re weeding and watering and monitoring but also noticing new leaves and tendrils, finding new little sprouts, sweating over the prep work of soil amendment and bed planning and starting seeds. And then there’s a long, slow stretch when your seeds are sprouting, doing what they’re meant to do: unfurling, storing up sunlight and water and nutrients enough to produce sugars or proteins in the form of flowers and seeds, following their biological imperative. You can’t rush them, and after all the fussing and setting things in place, you’re left to just watch.

After the active, dirt-under-the-fingernails weeks of prepping and planting, it feels like throwing on the brakes. The first three or four leaves are exciting; after that it becomes hard to measure whether the corn stalks really are getting bigger, if the marigolds are taking. You see your seedlings, and the deadline of that first frost, and you try to do the math about how many tomatoes or beans or whatever you can expect to get before everything dies back for the season. It’s a lot of fretting and a good amount of maintenance, but the middle point of a season sometimes feels helpless and slow.

And so it goes with life. It’s been a big few years in my house—in everyone’s house, really, if you count surviving the worst of a pandemic and trying to find what a new normal might look like. Beyond that, my husband and I have each just finished big projects—mine which defined the latter half of my 20s, his the culmination of a job he’s had since his teens—and now we are sitting in the long aftermath of these endeavors, tired from the work and waiting to see how it bears fruit. We’re puttering, maintaining, tweaking things here and there, but there’s also a sense of both of us at loose ends, the slow sluggishness of midsummer hitting. It’s not quite time to start thinking about the next season, to talk about new plans in anything but the most abstract terms, but the bulk of this season is over. I think we might call it a time of rest.

It’s not the full rest of deep winter—there’s plenty to do in a garden between planting and harvesting time—but that work is the daily maintenance work of staying alive, keeping things tidy, warding off bad habits and the like. If you’ve been used to building, to thinking about things in the big picture, this kind of work can feel small. Big things may still be happening, but they’re often outside your field of vision, seemingly slow or insignificant or invisible until they’re not. In any case, it’s out of your hands.

This is a hard lesson to learn. If I care so deeply about having a ripe squash, grown in my own garden from a seed that I planted, one would think that I would be able to ensure that outcome, that by wanting it badly enough I could bring it about. Instead, I’ve spent most of the summer trying to outwit pill bugs, who seemed intent on devouring many of the things in my garden as they came up. I also ended up building an ad hoc trellis, as the three sisters system I thought would help support beans ended up with bean vines not so much running up corn stalks for support as rapidly outpacing them and tangling up in each other. Early in the spring, I mistook a poison hemlock for a fern I half-remembered planting in the fall and waited for it to get hip-high before donning full protective gear to pull it out, taproot and all, only to find out that it had nearly choked a bleeding heart plant that I had chosen because it reminded me of the first garden I kept as a child. Challenges that seem small can be devastating; new plans and supports need to be put in place; you let things go awhile down the wrong road. It may not feel exciting, but it’s important work to stay on top of those things.

And now it’s nearly September, and all that everyday work is bearing fruit. I’m able to put meals on the table that I oversaw from seed to dish; I can snack on the plants growing in my garden. It feels, again, like new things are happening, also outside my control but now visible, embodied and clear. It may be that in the bigger scheme of things, my household is not quite yet in a season where our work becomes visible. But we can keep doing it and wait until the day we can see the fruits of our labor.