Days of wanting

My family didn’t want to go to America at all; we left Vietnam on pain of death.

Century illustration (Source images: Getty)

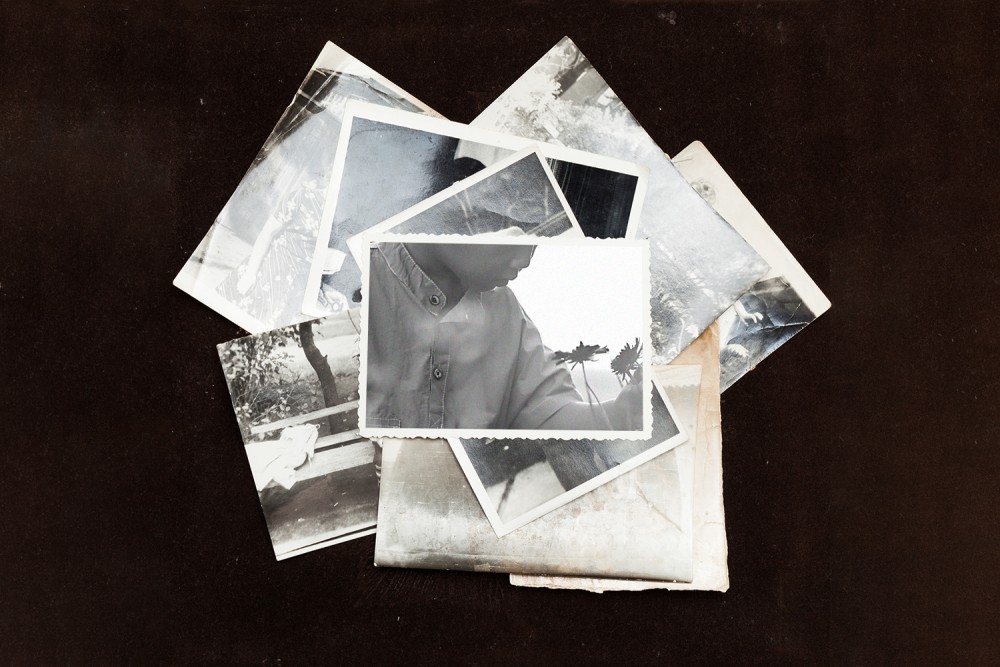

Shortly after arriving in America as a war refugee in 1975, my brother David was hit and killed by a car. I was five and he was six. It was my oldest brother Thierry’s birthday, and the rest of the family was busy making preparations for the party. David and I decided to pick some flowers across the street. He was in front of me, just barely ahead. I don’t know if the driver who hit him never saw him or just couldn’t stop in time, but my next memories are David’s body on the street and people screaming and running around. Emergency services arrived, and I recall being excited by the sirens and the big, interesting vehicles, the sounds and the thrill of it all processed through the mind of a five-year-old lacking a working concept of death. I guess I am grateful that I don’t remember much more.

This is my first memory. It’s not that nothing else happened before that point; this was just my mind’s way of marking a beginning. The beginning of an American life.

We had come to America at the end of the American war in Vietnam. My family was from the aristocratic North, meaning we were wealthy, landed, and elite. It also meant we were hated by the Communists, and when they took control of the North it was time for us to go, which we did—first to the central mountainous area where I was born and then south to Saigon. America would lose 60,000 soldiers to this long, bloody war; Vietnam would lose more than 3 million people, most of them civilians. In the spring of 1975, when it became obvious that America could not win the war, the US government enacted legislation that granted political asylum to 10,000 “Vietnamese friends of America”; in less than a month, 140,000 came. It was an act of extraordinary generosity.

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

My family made it out, but not all of us. My dad was away on a business trip on the day we were evacuated out of Saigon, and Mom had to decide whether to wait for him or lose our only opportunity. We left without my father.

We arrived in America with nothing, but we were better off than those who never made it over. Mom struggled raising the four of us on her own; she, like her mother before her, had been raised by nannies and had little idea what she was doing. She has sometimes said that David’s life was characterized by a lingering sadness, even before his death. I often wonder if that’s just the sense she has of children. We moved a lot, 14 times before high school, as Mom cycled between jobs, new dreams, lost jobs, deflated dreams, over and over again.

I was picked on a lot because I was Asian. No matter where we lived or in what kind of neighborhood, White kids, Hispanic kids, sometimes even other Asian kids picked on me—people I knew, strangers on the street, even friends. The slurs seemed a permanent feature of my life and identity. Chink. Jap. Gook. Nip. Though the kids knew all these words, their only notion of Asian was Chinese or Japanese. They definitely couldn’t imagine Asians as Americans. As Wittgenstein said, “The limit of your language is the limit of your world.”

My brother Thierry taught me to fight, and that I did, early and often. I remember one time, some kids were messing with me, calling me Bruce Lee and that kind of thing. So I fought them. The irony escaped me.

That time of my life, epitomized by David’s death, I refer to as “days of wanting,” following Psalm 23’s “I shall not want.” It was a lot of wanting in those days. Wanting for money. Wanting for stability and security. I wanted friends. I wanted to belong, to feel at home someplace, to be validated for whoever I was.

I definitely wanted a girlfriend. In second grade I met Jennifer Pillsbury, a classic beauty if ever there was one, and from then on it was one long string of rejections all the way up until Carrie Cheung agreed to date me—in 12th grade. She’s been Carrie Tran now for 25 years.

Unlike the stereotypical Asian American kid who excels in school, I barely got by, consistently struggling with discipline, regularly shaming my poor mother with “needs improvement” marks for behavior. In contrast to some Asian families, mine did not come to America because we wanted to get a good education. My family didn’t want to come to America at all; we came on pain of death. Survival drove us, not good grades.

In my senior year of high school I began going to church at the Chinese Baptist Church of Orange County, though I was not Chinese, not Christian, and definitely not Baptist. I’d like to say I went to CBCOC because I found God there, but mostly I found a place where it was OK to be Asian American. It was the social validation that caught my attention, and God through God’s church became for me the author of that validation.

None of these things, unfortunately for those of us who want the meaning of things to shine off the pale surface of life, bears meaning in itself. Rather, they all find meaning in that event marked in our liturgy as a Friday, a Saturday, and a Sunday during which our Lord was crucified, buried, and resurrected, an event which explodes our every attempt at and every desire for meaning. It is here, this beginning and end to our days of wanting and homelessness and lost brothers and found identities, that we will find our end in the One who has no end.