I May Destroy You takes us on a quest for wholeness

As Arabella struggles to remember the night she was assaulted, other memories emerge as well.

In the penultimate episode of Michaela Coel’s brilliant, riveting HBO drama I May Destroy You, the lead character, Arabella, finally has a breakthrough as she plots out the memoir she’s been trying to write all season. She stands back from her bedroom wall papered in Post-it notes.

“I thought you were writing about consent,” her writing coach says.

“I thought so too,” she remarks. In that moment she realizes, and we realize with her, that while I May Destroy You is a story about rape and consent in the social media age, it is about a lot more, including Arabella’s search for wholeness.

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

Coel wrote all 12 episodes, directed most of them, and stars as Arabella, a Black British writer and social media influencer with the precarious success of the social media age: she is famous enough to be recognized on the streets of London but still lives paycheck to paycheck in a small flat. After self-publishing a memoir on Twitter, she gets a real book contract, with a looming deadline and the writer’s block that comes with knowing she is supposed to have something important to say. Hoping to shake off some nerves, she goes out with friends, her drink is spiked, and she is raped while semiconscious.

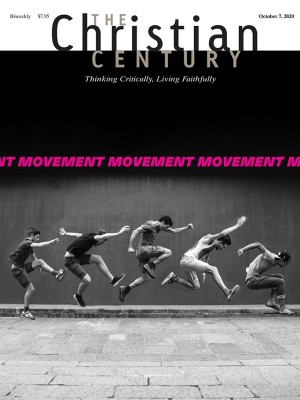

This happens in the first episode. The rest of the show deals with the aftermath of her attack, an event she cannot remember clearly. Unused to seeing herself as a victim, Arabella is not sure how to respond. She undertakes a rigorous program of self-care and creative expression, seeking out pottery and dance classes. She joins a support group for victims of sexual assault. She discovers feminism and a new connection to her identity as a woman. She becomes an avenging social media angel, bashing the toxic privileges of White masculinity and absorbing the grief and rage of thousands of her supporters. Her closest friends, Terry (Weruche Opia) and Kwame (Paapa Essiedu), are her safe haven, even though their friendship is tested by Arabella’s crusade for vengeance.

As she grows increasingly virulent in her attack on all attackers, she begins to see lack of consent everywhere she looks. Is hooking up with a stranger on a dating app under false pretenses a situation with lack of consent? Is pressuring a friend to have sex with someone they like a form of assault? Where is the line between lack of respect and lack of consent? Initially these questions are a form of self-protection as Arabella retreats into an increasingly black-and-white reality, even to the point of lashing out at those closest to her. But as she struggles to understand what has happened to her, her search for truth and righteousness turn inward.

In no way does the show suggest that rape victims have more moral work to do than rapists do. But it does suggest that healing for Arabella is not possible if her process stops with rage and indignation. Her quest is not just for justice—which is rarely granted rape victims, as Arabella learns in her process with the police—but for wholeness. This is deeply ethical work that transforms her self-understanding and her closest relationships.

Despite these very serious themes, the show is surprisingly funny, delicately poignant, and so visually gorgeous you can’t look away. Arabella and her friends exude freewheeling glamor and wittiness in their creative and personal freedom. But they are also young adults moving from a carefree—and often careless—life to the work of caring for each other. As Arabella struggles to remember what happened to her on the night of her assault, other memories from her life come flooding to the surface: memories of her father’s infidelity, her own callousness with previous romantic partners or friends, choices to protect people who hurt her or hurt people who tried to protect her. As her therapist gently explains, integrity means accepting that some of the darkness you want to protect yourself from is also inside you.

Shortly after her writing breakthrough, Arabella confesses that she knows a secret Terry has been desperately hiding, one that hurts Arabella deeply. Their eyes meet, they are both on the verge of tears, and they reaffirm their friendship. We know the Arabella we met ten episodes earlier would not have been able to offer this kind of forgiveness nor been able to receive Terry’s vulnerability. This is a hard-won ethics of care.

Standing in front of the Post-it notes, realizing that this story is about far more than the modern rules of consent, her writing coach says, “I don’t understand it.”

“I do,” Arabella replies. She is writing the very show that we are watching.

A version of this article appears in the print edition under the title “Becoming whole.”