Take & Read: American religious history

The Last Puritans: Mainline Protestants and the Power of the Past, by Margaret Bendroth (University of North Carolina Press, 258 pp., $27.95 paperback). This smartly conceived, gracefully written work weaves four under-studied stories into one. The first is a fairly straightforward history of the Congregationalists (who later became part of the United Church of Christ), especially in the 19th and 20th centuries. The second forms a study of how religious practice primarily takes place not in denominational headquarters or in doctrinal wrangling by convention delegates but in the daily life of local congregations. The third constitutes a contribution to the relatively sparse academic literature on the growth of mainline denominations. The fourth is an imaginative exploration of how the memory of tradition—of Plymouth Rock, of First Church on the Village Green, and similar icons—has served as a perennial touchstone of self-definition, with both steadying and divisive results.

The Other Catholics: Remaking America’s Largest Religion, by Julie Byrne (Columbia University Press, 432 pp., $29.95). Liberal independent Catholics not recognized by the Vatican number something like a million adherents scattered across thousands of meeting sites. They are united by commitments to apostolic succession, seven sacraments, and reverence for saints. But they also display a continually shifting array of unexpected emphases, often—though not always—including women’s ordination, gay marriage, radical social justice, sacramental inclusiveness, liturgical innovation, and (Byrne quips) concerns about “how much woo-woo was too woo-woo.” Reviewers have called this book brilliant, landmark, vivid, captivating, and (my favorite) rock solid. Drawing on deep research in archives as well as surveys, interviews, and ten years of field research and participant observations, the book is as important for the self-reflexive methods it reveals as for the remarkable story it tells.

The Columbia Sourcebook of Mormons in the United States, edited by Terryl L. Givens and Reid L. Neilson (Columbia University Press, 480 pp., $90.00). In proportion to their numbers, Mormons may enjoy the richest store of historical texts, both primary and secondary. The latter include survey overviews and dozens of excellent monographs. This collection of documents, edited by two of the ablest and most prolific of Mormon historians, provides the most comprehensive sourcebook available. The documents run from the 1830s to the present, embracing a variety of genres and perspectives. The editors’ elegant introductions to each of the eight chapters (theology, scattering, gathering, politics, ethnicity, sexuality, education, and practice) alone are worth the volume’s hefty price. They balance materials that exhibit the enduring power of institutional authority with ones that reflect the persistence of variety, resistance, and outright dissidence among rank-and-file members. It’s a treasure.

Dispensational Modernism, by B. M. Pietsch (Oxford University Press, 272 pp., $74.00). This book offers a stunning reconstruction of the intellectual roots of fundamentalism. Between 1880 and 1920, Pietsch argues, American religion found itself dramatically reshaped by converging waves of social and cultural change. One of the most enduring products of that convergence was an eschatological system commonly called “dispensational premillennialism.” Pietsch calls it dispensational modernism because it was simultaneously premodern and modern. Growing from trends in quantification, taxonomy, and technology as well as religion, it flourished in institutional networks such as Moody Bible Institute and in the writings of the autodidactic Bible teacher C. I. Scofield, whose Scofield Reference Bible, published by Oxford University Press in 1909, was a perennial best seller. Historians may or may not agree with Pietsch’s arguments, but they cannot afford to go around them.

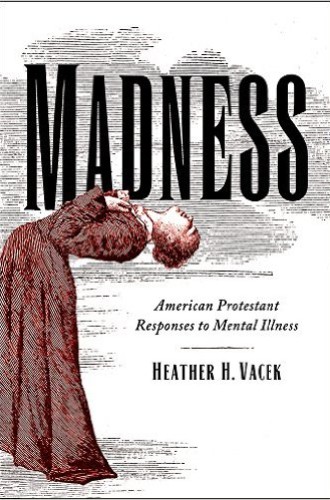

Madness: American Protestant Responses to Mental Illness, by Heather H. Vacek (Baylor University Press, 283 pp., $39.95). This timely and deeply moving study has garnered wide media attention. It shows how American Protestants have addressed and, more often, failed to address mental illness in their congregations. They have been quick to offer pastoral care for physical ailments but strangely reluctant to offer it for the equally pervasive and persistent problem of mental infirmities. The reasons are multiple, including the steady medicalization of treatments, theological prejudices about mental maladies as retribution for sin, and characteristically American notions of self-help entrepreneurialism. The first five chapters examine representative figures across American religious history: Cotton Mather, Benjamin Rush, Dorothea Dix, Anton Boisen, and Karl Menninger. The final chapter brings the story home, challenging Protestants to examine their unsteady history of dealing with mental illness. (See review "Medicine for madness.")