Medicine for madness

I relate to physical sickness more easily than mental illness. So does our culture.

As someone with a bone disorder leading to injury, surgery, and disability, I’m intimately acquainted with what Susan Sontag called “the kingdom of the sick.” When I meet fellow citizens of that kingdom—other people with my disorder or a friend with rheumatoid arthritis—our common experiences forge an immediate connection.

The kingdom of the mentally ill has some terrain in common with the kingdom of the sick. I have friends, for example, with whom I share the burden of taking daily medication—for them an antidepressant, for me opioid pain relief. In both cases it’s necessary for daily functioning and also widely stigmatized in a culture that likes to believe that with the right all-natural diet or physical practices we can avoid Big Pharma’s wily clutches.

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

But the kingdom of the mentally ill lies in a poorly mapped corner, a foreign landscape I struggle to understand. I have a childhood friend who has cycled in and out of psychiatric hospitals for more than two decades. Every few months she starts calling, sometimes several times a day, to tell me what simple thing she needs (money, a place to stay, a job, a lawyer, her ex-boyfriend’s love). I can relate to a condition that leads to loss of control, stigma, isolation, and pain. But I struggle to relate to a condition that alters someone’s reality so deeply that she doesn’t perceive herself as sick.

There’s a similar disconnect between the history of physical illness and that of mental illness. Siddhartha Mukherjee’s award-winning narratives, The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of Cancer and The Gene, have a clear momentum. Early efforts to understand cancer or genetics may have fumbled; mistaken notions may even have held sway for decades. But over time, understanding increased in measurable ways and led to real advances in knowledge and treatment.

The history of mental illness, in contrast, reveals repeated cycles more than a linear movement. Understandings of mental illness as rooted in the body and/or brain give way to understandings of mental illness as rooted in psychosocial circumstance, and then revert. Mentally ill people have benefited from more effective medications, the shutting down of institutions where inhumane conditions and barbaric treatments were commonplace, and greater awareness of how frequently conditions such as depression affect our neighbors. But we’re also struggling to find therapeutic options for people discharged from institutions without adequate community care in place, constrained by a medical system that favors cheap medication over therapy, and stymied by rising rates of disorders such as autism. These dilemmas are at least partially rooted in the fact that it’s not clear what causes mental illness—measurable bodily processes, life circumstances, or both.

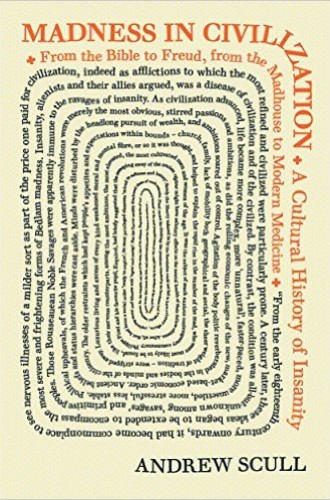

Andrew Scull, who teaches sociology and science studies at the University of California, San Diego, presents a comprehensive history of mental illness in his hefty but engaging volume. Scull demonstrates how early traditions, including Hippocratic, Galenic, Islamic, and traditional Chinese medicine, located insanity at least partly in the body. Many of these traditions were also surprisingly holistic, recognizing a social component of mental illness for both the afflicted and their families. Moving on from the ancient world, Scull takes readers on a brisk but thorough tour of the next centuries, from the medieval preoccupation with sin as the fundamental cause of all illness to the first hospitals (which were meant more for travelers, orphans, and the destitute than for sick people). A few early hospitals kept small wings for “the insane,” who didn’t get much in the way of treatment. But until the 18th century most mentally ill people were cared for at home.

At that time a “new geography of madness” emerged, with mentally ill people housed in asylums overseen by “mad doctors” and “alienists” who adopted the latest theories about causes and treatments. Mental illness was attributed to the pressures of civilization (e.g., the “English malady” or “nervousness” affected those whose well-bred but delicate constitutions buckled under the weight of an increasingly complex civilization) or, amid the eugenics movement of the late 19th and early 20th centuries, to inborn degeneration. Scull covers Freud and the rise of talk therapy, which rooted mental illness in symbol and meaning rather than body or brain, and the horrific treatments (including lobotomy and injections of malarial blood and insulin to induce fever and coma) employed on shell-shocked soldiers and others in the first half of the 20th century. He ends with our current psychiatric system, noting that “pills have replaced talk as the dominant response to disturbances of cognition, emotion and behavior.”

Mental health benefited from a few key advancements, such as connecting the syphilis bacterium with general paralysis of the insane (GPI)—the dementia and neurological impairments of untreated syphilis, which affected about 20 percent of men admitted to European and American asylums in the 19th century. But, “above all” and throughout history, “madness remains remarkably mysterious and hard to comprehend.” Another common feature of every era is that mentally ill people are mistreated, marginalized, and especially prone to misery. Scull notes that “the incidence of serious illness and mortality in [the mentally ill] population has accelerated” in recent years. He laments that the Gadarene demoniac from whom Jesus cast out a legion of demons “would scarcely be the last occasion when insanity was seen as an affront to civilized existence and associated with nakedness, with chains and fetters, and with the movement of the madman to the very margins of society.”

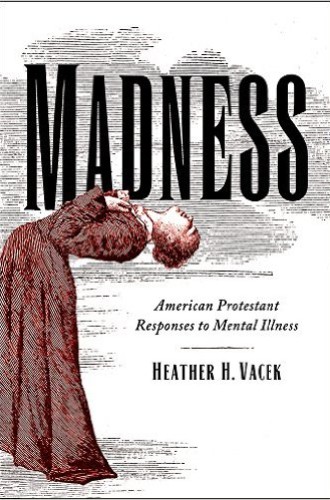

Heather H. Vacek provides a more detailed history of several of the figures covered in Scull’s book, including medical reformer Benjamin Rush, advocate Dorothea Dix, and psychiatrist Karl Menninger, as well as preacher Cotton Mather and pastor Anton Boisen. Each of them “responded to mental affliction with a sense of moral obligation and Christian duty, and all, implicitly or explicitly, claimed theological authority as they defined and addressed suffering.” Vacek, who teaches church history at Pittsburgh Theological Seminary, also examines historical contexts to expose the “pattern of concealment and inattention” typical of both Christian and cultural engagement with mental illness.

Vacek focuses on how her subjects construct relationships between medicine, theology, and Christian practice. Puritan Cotton Mather, for example, believed that all illnesses were connected to God’s will and human sin, yet “offered no condemnation of those afflicted with mental illness” and embraced medical science alongside theology as a tool to understand and treat illness. Benjamin Rush, a Revolution-era physician and “the father of American psychology,” saw mental illness as primarily a medical problem to be treated by doctors, but he also believed that Christians “had a responsibility to address it through medical innovation and advocacy.” Dorothea Dix “aligned fully with the optimism and hopefulness of the Unitarian movement” in believing that Christians are responsible for using their intellects to identify and remedy social problems. By advocating for state-funded asylums, Dix “pioneered Protestant advocacy for institutional reform.”

Anton Boisen was a clergyman who, confined for a time to an asylum, found a system “far different from the idyllic haven imagined by Dix in the prior century.” Believing that many mental illnesses “reflected acute spiritual trouble” that clergy were not trained to address, Boisen instituted clinical pastoral education, a program in which seminary students served in asylums and reflected theologically on their work there. Seminaries still require CPE today, though it more often takes place in hospitals.

Vacek’s final case study is of Presybterian Karl Menninger, who with his brother founded one of America’s best-known psychiatric clinics in Topeka. Menninger “drew a distinct line between sin and illness,” believed that clergy had a mandate to use the pulpit to encourage moral and mental health, and helped bring psychology and theology together in the field of pastoral counseling.

Following a series of thorough if somewhat dry case studies, Vacek presents an impassioned and convicting argument for a more robust Christian response to the suffering of mentally ill people. American Protestants, Vacek argues, have largely given over care of mentally ill people to the medical system, focusing on other causes. She calls Christians to reclaim Christian hospitality, which goes beyond coffee hour to draw “together guests and hosts into relationships of mutuality,” and to question our cultural insistence “that humanity is good only when useful or productive.” Proposing four steps involved in true hospitality—welcome, compassion, incorporation, and patience—Vacek offers examples of what these practices might look like in a congregation.

While the world offers different scripts, Christians remember that where suffering exists—especially where suffering exists—Christ remains in relationship with us. When the world deems those with mental illness [or, we might add, refugees, Muslims, black men, or police officers] as frightening, unproductive, unwelcome, and “other,” Christians embrace them as suffering, frustrated, welcome, and “just like us.” Being damned by association should be an expected part of Christian witness.

Scull and Vacek have given us far more than engaging, readable history. Within their rigorous accounts lies a humane call to pay attention to lives that have been hidden, demonized, and stigmatized.