Reckoning with racism

The opening line of Ken Follett’s Pillars of the Earth might be one of the most chilling ever written: “The boys came early for the hanging.”

The current political context is forcing Americans to discuss race, and churchpeople have some serious reckoning to do. Not only did the church turn a blind eye to racism, but congregations would often let out early on days there was to be a lynching in the town square so parishioners could get a good seat for the festivities. The church came early to the hanging.

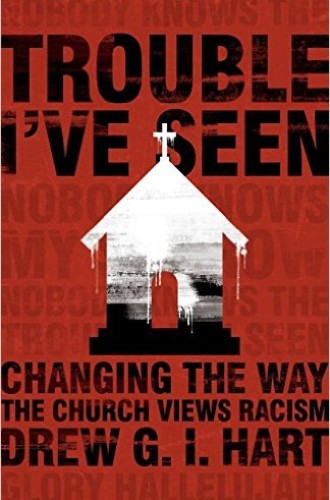

Pastor, activist, and scholar Drew Hart calls readers to investigate how, throughout American history and today, the church not only condones but also contributes to antiblack racism and white supremacy. Why does the church participate in modern-day lynching, or at most turn a blind eye, rather than protesting as our faith would dictate?

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

Hart writes from his own experiences in a mixed-race elementary school, a white suburban high school, a Christian college, and as a pastor in Pennsylvania. Racialization plays out in various ways in each of these settings. In the first and last chapters he shares experiences black men in his family have had with law enforcement.

He also brings to bear, concisely but exhaustively, the history of how race was formed in the United States. “Whiteness” emerged in contrast to distinct European immigrant identities. Irish, Jewish, Italian, and Portuguese people were not initially considered white. Hart examines how these immigrants opted into a white identity to gain access to jobs, housing and better neighborhoods. It gave them access to juries of people who saw them as peers. Adopting whiteness cost them their culture, ancestral ties, and some of their humanity, but it gave them the power of being the norm, with all the privileges that affords.

Hart demonstrates how America’s culture of antiblackness is grounded in a deeper and more invisible culture of white supremacy. White supremacy is manifest not only in the ways that individuals benefit from white privilege, but also the cultural and institutional construction of whiteness as normative and superior. Hart calls readers to notice how “centering whiteness” creates a culture that exploits and destroys black lives and all lives of color. He also reveals how respectability politics—the notion that behaving like middle-class white people can save people of color—harms communities of color and keeps white supremacy in place. Trouble I’ve Seen is not oriented solely toward the white Christian community: it invites people of color to engage in the work of liberation as well.

Hart uses scripture throughout the book and points to Jesus’ own marginality, the threat of Jesus’ existence to the Roman Empire, and the ways in which Jesus honored women and other people on the margins.

Hart occasionally tends toward the prescriptive. But his recommendations for individuals and congregations in the final chapter are concrete and significant. His theological framework in the last section of the book is beautiful in its claim that this work liberates all people to live more deeply into God’s vision for us as individuals and as a community. And at the center of this framework is Jesus.

Hart sees Jesus as a poor Middle Eastern man who lived his whole life in an outpost of the Roman Empire, who was shaped by oppression and raised to overcome it. Ignoring this true Jesus, Hart argues, is directly connected to our nation’s legacy of slavery, genocide, violence toward women, and xenophobia. “We must reorient our lives to make the true Jesus the center of our lives. The church must decentralize the white male figure’s preeminence. Despite how people often hear this language in dominant culture, decentralizing white male prestige is not an attack on white men. At its heart, it is the opposite: it is a humanizing project” (emphasis added).

The Black Lives Matter movement started with a love letter that cofounder Alicia Garza wrote to her community on Facebook after George Zimmerman was found not guilty of the murder of Trayvon Martin. She closed her note with this statement: “Black people. I love you. I love us. Our lives matter.” To Hart’s point about centering whiteness, there is something tragic in the fact that so many white Americans, including white progressive churches, are offended or threatened by a statement of love. “Black Lives Matter” affirms that even though we are under attack, even though the world around us does not acknowledge our worth, we have value.

Jesus, who was human as well as divine, watched his own faithful brothers’ and sisters’ humanity being constantly denigrated by the Empire that controlled their lives, their resources, and their governance. All too frequently we forget that when Jesus speaks of the dignity and worth of the people in his midst, he speaks primarily of people with little power or agency. Because we forget that truth, we don’t see that the message that Black Lives Matter is as consistent with Jesus’ teachings as the notion that a Samaritan had worth or that a woman usually expected to do cleaning and cater to guests had the right to study alongside the men gathered at Jesus’ feet.

White America’s fear of the Black Lives Matter movement is just one example of why Hart’s book is such a necessary challenge to the church. Without such confrontation, the church will continue, sometimes without even noticing, to come early to the hanging. By doing so, we participate, again and again, in the crucifixion.