Poetic nothingness

Flannery O’Connor once commented in a conversation about the mystic philosopher Simone Weil: “I would like to write a comic novel about a woman—and what could be more comical or terrible than an angular intellectual proud woman approaching God inch by inch grinding her teeth?” Later, however, O’Connor admitted: “My heroine already is, and is Hulga.”

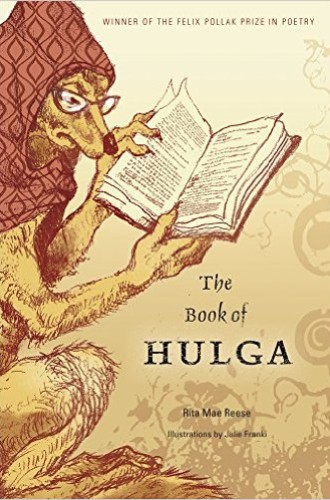

The Hulga to whom O’Connor refers is the protagonist of her short story about the odd workings of God’s grace, “Good Country People.” Hulga is also the center of Rita Mae Reese’s new collection of poems, which won the Felix Pollak Prize in Poetry from the University of Wisconsin Press.

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

To fully understand Reese’s work, familiarity with O’Connor is helpful, if not necessary. Although Reese provides notes about O’Connor and Weil at the end of the book, I found myself having to reread “Good Country People” and to shamelessly Google the names and incidents in O’Connor’s life cited in particular poems. Some effort, therefore, is necessary for the reader to navigate through these often allusive poems. However, the poems reward the persistent reader.

The central confrontation in Reese’s poetry is with nothingness, an elusive concept that takes on many forms. (O’Connor’s Hulga begins “Good Country People” as an atheist and is brought—perhaps—to faith through the satanic Bible salesman Manley Pointer, who steals the crippled Hulga’s wooden leg and brashly claims, “I been believing in nothing ever since I was born.”) In “The Given Lines,” the speaker claims, “Hell is nothing, God is nothing & we / are the nothing lost between.” However, the poem ends (as does “Good Country People”) with some hope of transcendence and life. This hope is experienced through the apt metaphor of digging, here presented with a startling flash of color: “Her heart, never still, digs its red hole, / forcing roots into the absence.”

Making meaning out of suffering and loss, one of poetry’s most fundamental aims, suffuses this collection. “The Given Lines” is one of Reese’s sonnets, which begin and end with lines by Weil. They ask the same deep questions that people of faith ask: How do we make sense of the seeming randomness of life, in which “we / don’t get to choose which part of ourselves / we’ll lose, or even to know what it is we’ve lost”? These are poems about the pains that wrack the human body: Hulga’s missing leg and her grief over her dead father, O’Connor’s pain from lupus.

Hulga is O’Connor, or rather the restless, angry part of O’Connor, the “bloody fist knocking on sleeping doors,” that prompts O’Connor to put her energies into writing in order to avoid falling into an abyss of nihilism prompted by mortality. God is “blank” in many of these poems, but God is also present in small but essential epiphanies, such as the realization that “there’s an unnumb heaven waiting for us / & that this pain is going to open the door” and “All children know, or should, / the sudden turns love can take.”

The Book of Hulga suggests that the way to God’s grace is through the mortifications and humiliations of the body, which both imprisons us (“One guard, one prisoner, / one cell—all Hulga”) and enables us to experience God sensually. We find such experience of God both through the physical world and, for the Catholic O’Connor, through the Eucharist: “Hulga can smell the Holy Ghost, / hear Jesus, taste God.” We are, for Hulga and presumably for Reese, “animals creeping forth / seeking their meat from God.” Through our very embodiment in “bony hillbilly hips,” we possess the means to approach God in prayer and to experience God as the dark “pond flooding the world.”

The best of Reese’s poems speak to sorrow and its survival. Reese ingeniously uses forms—short poems, long poems, short lines, long lines, punctuation, and lack of punctuation—to explore philosophical and theological questions. The book includes magnificent illustrations by artist Julie Franki that complement Reese’s searing poems. I found most effective those poems that require only a passing familiarity with O’Connor’s work: those poems in which Reese provides the reader with the needed context. The gorgeous “Welcome to Milledgeville” (O’Connor’s hometown) describes loneliness with heart-stopping images and concludes: “sometimes all you can hear / is the beating of wings.” The glorious “Flannery, Are You Grieving?” is in conversation with Gerard Manley Hopkins’s poem about mortality, “Spring and Fall.”

Reese’s webpage contains further resources on O’Connor, Weil, and philosophy, including this quotation from Thomas Merton: “At the center of our being is a point of nothingness which is untouched by sin and illusion, a point of pure truth, a point or spark, which belongs entirely to God.” Reese’s poems invite the reader to plunge into this nothingness, which is, by its very definition, all.