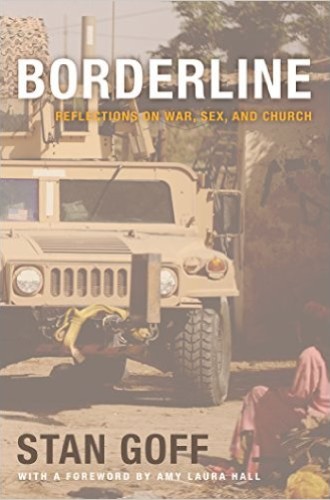

Borderline, by Stan Goff

The news media have recently been ablaze with stories of police brutality, campus rape, military conflict, and mass murder. Such violence is sometimes attributed to race or religion, at other times to alcohol or mental illness. In an eclectic set of essays, Borderline: Reflections on War, Sex, and Church, Stan Goff urges us to see a single thread running through virtually all such stories: masculinity. Moreover, he finds Christianity undeniably complicit in the cultural norms that encourage and reward male violence.

Such a critique is not new. Feminists have been decrying violent masculinity for a century, while for millennia Christian pacifists and witnesses have heaped shame upon kings, popes, and soldiers. What makes Goff’s argument remarkable is the way feminism, Christian pacifism, and sophisticated theological analysis have been pulled together by a career military officer turned antiwar activist who also happens to be a refreshingly accessible writer. “My engagement with feminism led me into the church, and war led me to feminism,” he writes. “There are probably few people who narrate their conversion to Christianity in that way.” Such startling incongruity demands our attention.

Goff argues that “masculinity constructed as domination, in war and in relation to women, is really just one story . . . of manliness, . . . [and] this very construction has steered the church away from the story in the Gospels.” To demonstrate this point, he presents “a rough genealogy of church-and-war alongside church-and-sex, in which the reader can discern how often, and often terribly, the church has allowed itself to be pulled away from the example and the teachings of Jesus of Nazareth.”