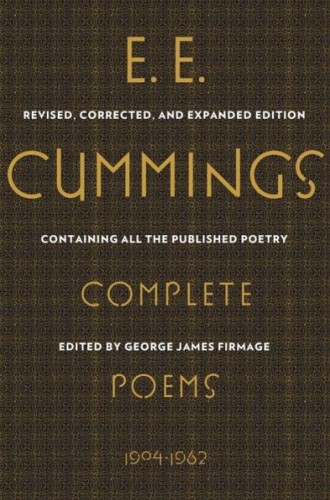

E. E. Cummings: Complete Poems, 1904–1962 and The Collected Poems of James Laughlin

Unlike many well-known poets, E. E. Cummings and James Laughlin didn’t write with metaphysical or philosophical ambition. But that doesn’t mean their poetry doesn’t matter.

Cummings wrote verse that is often praised for qualities that philosophically ambitious poets would be loath to display: childlike simplicity and whimsy. His 1958 collection, 95 Poems, included in Complete Poems, is full of such wonders. For example, #16 begins: “in time of daffodils (who know / the goal of living is to grow) / forgetting why remember how / in time of lilacs who proclaim / the aim of waking is to dream.” What look to be typos in a Cummings poem usually are not, and those that are have been “corrected” in this beautiful new reprint edition by the people at Liveright.

The poems in Cummings’s 1963 volume, 73 Poems, also lack titles, so an index of titles would be both impossible and unnecessary. Even the index of first lines, which is standard in collected editions, looks ridiculous. First lines include “a-” and “a gr,” as well as “as” and “b.” It seems almost silly, but readers will want to be able to look up a familiar poem. And such a method is all the more striking when we encounter first lines such as this one: “unlove’s the heavenless hell and homeless home,” from #91 of 95 Poems.