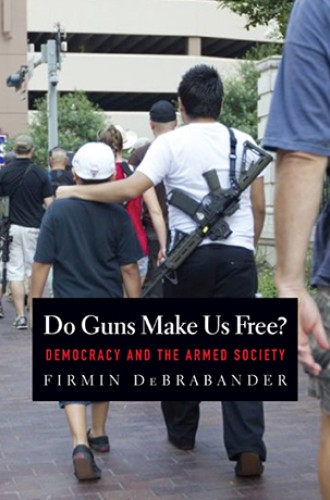

Deadly illusion

Firmin DeBrabander, a philosophy teacher at Maryland Institute College of Art, has written a judicious exposition of the crisis of guns in our society. He pays particular attention to the ideology, claims, and consequences of the work of the National Rifle Association. To the question of his title—Do guns make us free?—he issues a firm and persuasive no. Guns do not make us free. Gun culture as it has emerged in U.S. society is antithetical to a democratic society because democracy cannot function in a culture of fear in which freedom of expression is intimidated.

Attention to the NRA means attention to the work of Wayne LaPierre, its chief spokesperson. DeBrabander gives LaPierre a good deal of air time, exhibiting the absurdity and skewed ideological foundations of the NRA.

Because DeBrabander is a philosopher, it is no surprise that his most interesting and important contributions are in the chapters where he looks behind the present shrill discussions to more elemental considerations. In chapter 2 he takes up the thought of Thomas Hobbes and John Locke. Hobbes concluded that we live in a “state of nature” that is wild, undisciplined, dangerous, and brutal—a war of all against all. Locke proposed instead that there is and can be a civil society that depends on respect for individual rights and individual property, which are sacrosanct and of ultimate importance.

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

The gun lobby appeals to Locke, arguing that guns are both private property that must be protected and the means of protection for all other private property. Thus they recruit Locke to support the gun culture and its claims for unregulated private gun ownership. DeBrabander turns Locke against such an argument. Locke insisted that commitment to civil society requires curbing the passion for life in a state of nature—so curbing private protection is essential for civil society. For Locke, we cannot have some members of civil society operating as if they were in a state of nature. The ludicrousness of such privatized action amid civil society becomes evident when we consider the Stand Your Ground laws that give warrant for private violence.

Even more compelling is chapter 3, which focuses on Machiavelli. DeBrabander asks: Given that guns are so dangerous and destructive, why do the governing forces support such violent permissiveness and do nothing to curb it? He finds an answer in the work of Machiavelli, who long ago observed that the prince can evoke loyalty from subjects by permitting them to keep arms and therefore feel empowered. Feeling so empowered, they gladly ally with the force and authority of the prince. Conversely, if denied their own arms, they will perceive themselves as the enemies of the prince.

The prince, moreover, may readily allow private arms because they pose no serious threat to his overwhelming force and authority. Private arms, Machiavelli understood, are a kind of palliative that ensures tacit support for the prince. Guns may indeed create danger and pose a threat to other citizens, but they are not significant enough to challenge the secure role of the prince. Implicit in this insight is the recognition that the gun lobby’s mantra that guns are a check on tyranny is a first-rate illusion, one that the prince not only can tolerate, but has a stake in fostering.

Around these shrewd insights from Locke and Machiavelli, DeBrabander builds a case about the illusionary power of the gun lobby. He observes that the gun lobby’s ideology is designed to generate deep and amorphous fear, which in turn makes guns a supposedly necessary resource for safety. The message from the nightly news that violent crime is rampant and at your door is supported by popular cop shows, in which crime is promptly countered and decisively resolved by force.

Such displays of violence, which make one feel fearful and then feel safe, are far removed from the real thing. On offer is an abstract violence that is staged, dramatized, and remote from the actual social reality of violence, which is not neat, clean, and unambiguous. As a result, DeBrabander concludes, “Gun ownership is primarily the interest of those Americans most remote from violence—rural and suburban middle-class whites.” When social chaos is displayed often enough, guns are believed to be required in response. The outcome of such an illusionary context is the creation of a society of danger—a world where the argument of the NRA rings true.

DeBrabander breaks through such narcotized thinking: “Who wants to live in such a world? And why must we think such a world is inevitable?” The gun lobby creates a world in which its solution (more guns!) is credible, but only if the fear is sustained and continually escalated. Thus voices for an open society are compromised and increasingly restricted, kept under surveillance, or silenced. The trust essential for democracy is diminished, and we settle for retributive justice and militarization of the police.

At bottom, the appeal of gun-mongering is fed by a sense of political impotence and helplessness. Of course, gun possession is not a real act of political empowerment; rather, it is an illusion in the drift toward fascism, in which constructed fear keeps people immobilized and withdrawn into private zones of security and therefore cut off from serious participatory democracy.

This is a compelling argument. But of course it depends on reasonable discussion, the very discussion that is impossible when we are seduced into a bubble of illusionary fear. There is no doubt that the argument of this book is of urgent importance. But the way from it to political action will be hard, long, and slow. The cycle of fear, illusion, and more fear is deathly. This book is a bold witness against that deadly cycle.