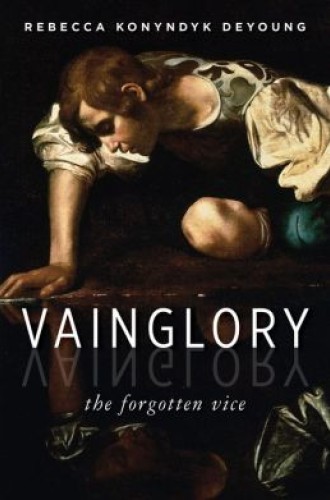

Vainglory, by Rebecca Konyndyk DeYoung

A friend tells me that there are two kinds of people in the world: those who post on Facebook and those who don’t. She and I are of the rarely posting ilk, and we can craft an expert and smug analysis of those who share all. See my good marriage, they boast. See my happy hour. See my long run. We can also build scathing critiques of the digital mechanisms that make others’ approval so immediate and quantifiable, and of the new grammar that enables our addiction to approval: Like. Comment. Share.

There’s a third kind of person in the world, of course: folks like my husband who use no social media at all, and thus retain the ultimate bragging rights of the unbragging. But Rebecca Konyndyk DeYoung would say that my friend and I, and even my husband, are as much at risk of vainglory—excessive attachment to others’ approval—as those who broadcast their eggs Benedict on Instagram.

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

As a Christian moral philosopher working in the classical tradition, DeYoung trains her eye less on easy targets like selfie culture and more on the reader’s soul. Vainglory is about all of us, she says, not just those who post photos of their children’s latest honor-roll report cards. Having investigated the seven deadly sins in her previous book, Glittering Vices, DeYoung now probes more deeply this most social and Christian of vices, which stalks the virtue-seeking person as much or more than one who has no longing to be good. Plumbing the works of the Desert Fathers, Augustine, and Aquinas, DeYoung suggests that this vintage vice deserves our attention not because it is particular to our time but because it is not.

Vainglory is considered a “capital vice” in classical Christian thought: it is the source, or taproot, of other vices. It appeared on Evagrius of Pontus’s list of eight vices in the fourth century, DeYoung says, but then it disappeared down some corridor of history, leaving only seven deadly sins on the well-known list. For modern Christians who assume that pride and vainglory are fungible terms, DeYoung offers Aquinas’s helpful distinction: the prideful person wants to be superior to someone else, while the vainglorious person wants everyone else to know it.

DeYoung attends to definitions with a philosopher’s eye for the architecture of an argument. She carefully demarcates the difference between prideful and fearful varieties of vainglory.

The prideful form takes pleasure in the accolades received for an actual virtue or success; DeYoung calls it “the sinful pattern of people who show off their glory-worthy selves.” This type often begins as the unself-conscious pursuit of excellence and over time devolves into glory seeking. Fear-based vainglory, on the other hand, is “not a show-off vice for excellence, but a cover-up maneuver for its acutely felt absence.”

For the general reader, this distinction is a helpful one, as is DeYoung’s discussion of vainglory’s “offspring vices,” including boasting, hypocrisy, and the “presumption of novelties”—which she suggests is medieval-speak for my teenager’s longing for an iPhone 6. But at times DeYoung’s careful definitional and analytical labors, which classify all versions and hybrids and varieties and cases, may stretch a little long for readers. Her fidelity to the classical tradition’s taxonomy of vices may baffle readers unfamiliar with it, and in the midsection of the book she risks losing readers unschooled in the tradition. For many readers, DeYoung’s chapter on vainglory in Glittering Vices would be sufficient coverage.

On the whole, however, she renders ancient Christian thought accessible and relevant to contemporary readers, using examples from popular culture and from her classroom at Calvin College to construct a lovely inquiry into this understudied but potent vice.

DeYoung claims that vainglory is not necessarily more totalizing now than it was in previous eras; thus the bulk of her book focuses on its personal, timeless forms. By narrating the sometimes humorous confessions of vainglory by fourth-century monks—including the one caught by a friend preaching a magnificent sermon to invisible congregants—she argues that nothing is new under the sun. Vainglory is ultimately a “problem of the heart,” DeYoung claims, and it was as problematic for ancient hearts as it is for ours.

Vice and virtue are hard to quantify, in both individuals and cultures. I’m certain that many of my status-updating friends are far less vainglorious than I, and it’s impossible to say whether Evagrius and his monastic peers were more or less vainglorious than me and mine.

But any study of vainglory in the 21st century should investigate this inescapable fact: the devices we cradle all day long are uniquely tricked-out vehicles for the vice. What Nicholas Carr calls “the shallows” of digital culture enables and nurtures vainglory in a way that Evagrius’s culture didn’t. DeYoung’s penetrating monocle, so carefully trained on the classical tradition, treats as peripheral spiritually significant questions that many readers face as we choose which parts of ourselves to broadcast. Vainglory might have been forgotten as a vice because it fell off the list of deadly sins; then again, it might be forgotten because it has been liked and favorited and retweeted right into the air we breathe.

Of her seven chapters, DeYoung’s strongest is her last, in which she takes up the fascinating question of whether vainglory can be considered a vice in the secular realm, considering that its definition is theological at root. If vainglory is essentially about stealing glory from God and hoarding it for ourselves, then it is unintelligible as a vice outside the house of faith.

This idea may explain why DeYoung’s project flows against the current of recent attempts to redeem vainglory’s adjacent concepts, narcissism and pride. In The Americanization of Narcissism, historian Elizabeth Lunbeck attempts to rescue a healthy narcissism from the clutches of cultural critics. And pride regularly gets spiffed up from selfish conceit into healthy self-acceptance, as seen most recently in singer Meghan Trainor’s shimmying booty pride.

Vainglory may seem to be a prime candidate for such a vice-to-virtue makeover, given that the second half of the word means goodness made visible. In its purest form, human glory is having one’s gifts or labors acknowledged by others. DeYoung’s book will help pastors envision how a Christian community can create a “culture of grateful dependence and shared goodness,” thus affirming its members in ways that allow them to “glory well” rather than tempt them toward vainglory. But she takes care to distinguish between the healthy glow of mutual affirmation and attentiveness, on the one hand, and a diseased ego need for approval, on the other.

An author who was a journalist or cultural critic may have found a way to call vainglory good. But DeYoung isn’t rehabilitating vice; she’s reminding us that God can redeem us from it. If glory is a gift, vainglory is a tarnished gift. DeYoung writes that the surest ways to stave off vainglory include silence and solitude, in which we have no audience for whom to perform. Such disciplines help us “realign our habits of thought and desire in the direction of seeking acknowledgment and affirmation from God first and foremost.”

In the end, whether you view vainglory as a problem of the heart or a problem of culture—or both—matters less than whether you consider it a vice or a virtue in disguise. DeYoung provides vigorous theological backing, rooted in ancient tradition, for calling a vice a vice. In so doing, she gives virtue-seeking people the language to name and the spiritual practices to resist all the vain things that charm us most—including our very selves.