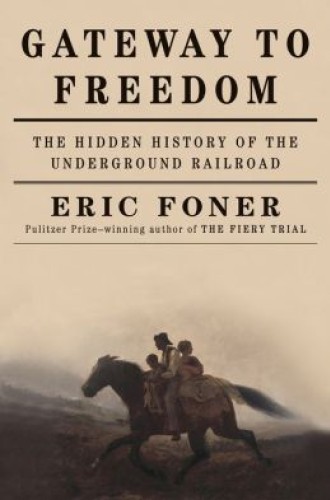

Gateway to Freedom, by Eric Foner

Demons harassed novelist Harriet Beecher Stowe. At least that’s how one artist of the 1850s caricatured the author of Uncle Tom’s Cabin. In that visual assault on the “little woman” who Abraham Lincoln supposedly said “wrote the book that made this great war,” an army of devils have invaded the world to put an end to her wickedness. One grabs her left hand. Another stabs her rear end with a pitchfork. Yet another latches onto her body from behind, while serpents coil around her feet. Behind Stowe is a large cavern labeled with the words “Under Ground Railway.” It is unclear whether the devils are pulling her from the darkness or endeavoring to shove her into it.

By the middle of the 1850s, when Stowe’s novel rocked the United States, the Underground Railroad was a whispered dream among people called slaves and a feared possibility to people called masters. It was discussed in newspapers and magazines. Some politicians berated it; others applauded it. There was even a popular song named after it. Eric Foner resurrects the history of the Underground Railroad, its powerful place in New York City, and how it helped Stowe and others bring about the titanic war that ended chattel slavery.

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

The institution of slavery had vexed the nation since its political and military inception in the 1770s. From the 1830s to the 1850s, the rising number of enslaved runaways and the escalated activities of abolitionists drove a wedge into American society. Free northern African Americans and their white allies opposed slavery in law and practice, and some of them participated in what they called “practical abolition,” which meant secrecy, illegality, and danger. Working with and for the Underground Railroad meant meeting in the streets to protest the recapture of alleged runaways, and it meant hiding people and the documentation of their movements.

Foner positions New York City as a key terminal on the Underground Railroad and emphasizes the heroism of a handful of individuals there. He weaves together the long history of slavery and resistance in the United States and the social ruptures slavery wrought in New York, a city economically tied to cotton production. Foner underscores how operatives for the Underground Railroad participated in a wide array of antislavery activities. These included not only hiding and shuttling individuals, but also defending fugitives in court, tirelessly raising funds for the campaign, and publishing accounts of fugitives’ experiences.

The heart and soul of Gateway to Freedom is an account book kept by Sydney Howard Gay, the editor of an antislavery newspaper. Gay recorded short accounts of more than 200 runaways a few years after the publication of Stowe’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin. Some short and some long, the accounts detail the ages of runaways, their work lives, and their methods of escape. In one, he listed Harriet Tubman as “Captain Harriet Tubman.”

Most readers of American history are probably familiar with Foner. Author of the most popular undergraduate textbook on U.S. history, he has taught at Columbia University for more than 40 years. For his scholarship on the 19th century he has won just about every prize an author can, including a Pulitzer for his work on Abraham Lincoln. A few years ago Foner hit the Comedy Central daily double as a guest on both The Daily Show with Jon Stewart and The Colbert Report. In this book he is again the model narrative historian, matching erudite analysis with graceful prose.

The book represents the high point of traditional history, but it also displays the frustrating limits of the genre. By reducing the complex past to prose on the page and by imposing narrative order on the dramatic commotions of lived experiences, Foner misses opportunities to uncover more about the Underground Railroad and to make meaning of the archives he adores.

For instance, he teases readers about the process of locating and working with the archival sources that make this book possible. Gay’s account book of shepherding people to freedom leaves Foner searching for the right metaphor. He writes that analyzing the Railroad is akin to solving “a jigsaw puzzle” where many of the “pieces have been irretrievably lost.” It feels like a “gripping detective story where the evidence is murky and incomplete.”

But Foner reveals very little about the evidence and how he got to it—or how it got to him. He puts thousands of words into analysis of the words within the archives, but the drama of the documents remains flat. Why is this only a history of people? What about Gay’s account book itself? How large was it? Did Gay use pencil or ink? Where was it hidden? When was it found? How did it get into the special collections at Columbia University? Foner approaches sources from the past as texts to be mined, but those sources are also something to be mined as material artifacts in their own right.

The form of the book also exposes the limits of traditional prose. Other than a few maps preceding its main text, it offers no images. The people, the places, and the tantalizing archival sources are presented only as textual characters. Gateway to Freedom perpetuates the sense that visual imagery, material artifacts, and other physical pieces of the world are for museums and heritage tours but not for articles and books. As a reader in the digital age, I wanted to click on the maps. I wanted to toggle through them, zoom in and out. For the archival sources, I wanted hyperlinks to see where I could find them, to be able to read the narratives and the newspapers. While traditionally published historical books rarely offer such material, there is no reason for it to be neglected or hidden.

Foner has written a beautiful albeit traditional book. It is perhaps the task of another generation of historians to tell how the fugitive shards of the past make their way to us.