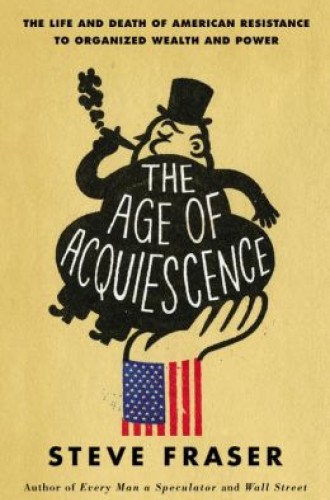

The Age of Acquiescence, by Steve Fraser

It has become commonplace to refer to the last quarter of the 19th century and the last quarter of the 20th (and beyond) as two Gilded Ages, using the phrase Mark Twain and Charles Dudley Warner coined in 1873 to describe their era of growing economic inequality and the domination of putatively democratic politics by a plutocracy.

There is much to commend the analogy, even beyond comparable statistics on the wealth and income of the richest 1 percent of the population and similar struggles to survive at the bottom of the social hierarchy. Thomas Piketty’s best-selling anatomy of the inequalities inherent in capitalism, Capital in the Twenty-First Century (2014), has its ancestors in Henry George’s Progress and Poverty (1879), Edward Bellamy’s Looking Backward (1888), and Henry Demarest Lloyd’s Wealth Against Commonwealth (1894). The rhetoric of the turn-of-the-century People’s Party would have been right at home had it been shouted in the fall of 2011 from the megaphones of the Occupy Wall Street movement in New York’s Zuccotti Park:

We meet in the midst of a nation brought to the verge of moral, political, and material ruin. . . . Our homes are covered with mortgages; labor impoverished; and the land concentrating in the hands of the capitalists. . . . The fruits of the toil of millions are boldly stolen to build up colossal fortunes for the few, unprecedented in the history of mankind; and the possessors of these, in turn, despise the republic and endanger liberty.