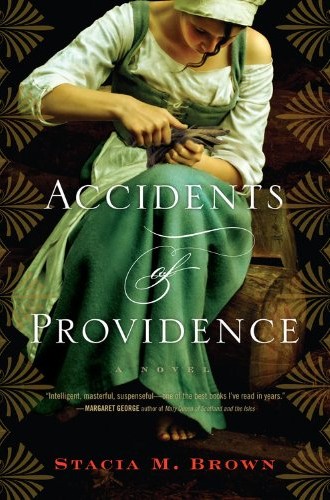

Accidents of Providence, by Stacia M. Brown

In a piece written a couple of years ago for the New York Times, Paul Elie laments the absence of serious engagement with the Christian faith in contemporary American fiction. Christianity, he argues, may appear as a cultural artifact; as a curious, ironic, or possibly toxic backdrop to the real action of a story; as something that a novel’s characters experience when they are growing up; or occasionally as an unexpected intrusion into otherwise secular lives. But that is all. Elie scans the literary horizon and wonders what happened to the O’Connors, Percys, and Updikes of the world, those writers “who can dramatize belief the way it feels in your experience, at once a fact on the ground and a sponsor of the uncanny, an account of our predicament that still and all has the old power to persuade.”

Elie should read Stacia Brown’s debut novel, Accidents of Providence. Brown, who has a Ph.D. in historical theology from Emory University, displays that unusual combination of exceptional literary talent and theological acumen that Elie finds wanting in American letters. Short-listed for the 2014 Townsend Prize, the novel is a work of historical fiction set in London during the turbulent period of the English civil wars. At once a romance, a murder mystery, and a theological parable, Accidents of Providence is a profound meditation on the nature of love and friendship, the active presence of God in the world, and the unavoidable spiritual tensions that arise between law and grace, necessity and possibility, self-sacrifice and self-preservation, and ultimately cross and resurrection when people try to live out their Christian convictions amid the complexities and ambiguities of human history.

The novel opens in November 1649 following the victory of the Puritan-dominated parliament over the Anglican-supported monarchy, the execution of Charles I, and the dissolution of the House of Lords. The parliamentary army fashions itself as the champion of the people but has suppressed the Levellers, a democratic movement composed largely of religious dissenters agitating for popular sovereignty, equality, voting rights, and religious tolerance.