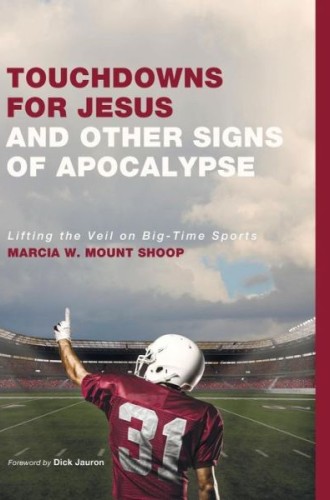

Touchdowns for Jesus and Other Signs of Apocalypse, by Marcia W. Mount Shoop

After Notre Dame upset Army in 1924, Grantland Rice penned one of the most enduring football tropes in American sports journalism. He used a biblical image—the four horsemen of the apocalypse—to emphasize the terminating power of the Fighting Irish backfield. Wreaking metaphorical famine, pestilence, destruction, and death on their gridiron opponents, they then led their team to an undefeated season.

Marcia Mount Shoop realigns football with apocalyptic thought by using the theological concept of “the unveiling of truth” to analyze the systemic dysfunction of professional football and of the near-professional football programs at major universities. She pursues this theological critique because, as she observes, sports “capture our imagination and elicit our deepest emotional outpourings much more than any religion does.”

Acknowledging that references to apocalypticism suggest a cosmic cataclysm, complete destruction, and final judgment, Mount Shoop nonetheless identifies the core of apocalyptic not with the end of the world but with its power to disclose distortions, defeat evil, and introduce radical change. She also understands that sports can provide vitality, strengthen community, and inspire transformation. An apocalyptic analysis exposes the demonic tendency of big-time football to perpetuate systemic sexism, racism, and classism, and it helps to restore the potential of sports to provide redemption by revealing people’s true identity. In light of the current domestic violence and child abuse cases involving National Football League players Ray Rice, Adrian Peterson, and Greg Hardy, her critique is all the more pertinent.