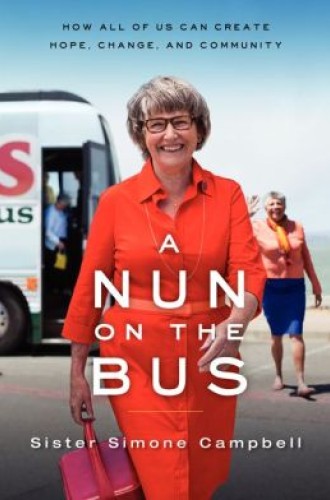

Pope on the bus?

A couple years ago I attended a large gathering where a Catholic sister, a well-known advocate on behalf of the poor, was present. Coming up behind her, I said, “Sister, you give me hope for the Catholic Church.” Without turning around she quipped, “I can tell you are not a bishop.”

Exactly two weeks after that event, the Vatican’s Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith formally censured the Leadership Conference of Women Religious for, among other alleged offenses, “disagree[ing] with or challeng[ing] positions taken by the Bishops, who are the Church’s authentic teachers of faith and morals.” The CDF’s document stated:

While there has been a great deal of work on the part of LCWR promoting issues of social justice in harmony with the Church’s social doctrine, it is silent on the right to life from conception to natural death, a question that is part of the lively public debate about abortion and euthanasia in the United States. Further, issues of crucial importance to the life of Church and society, such as the Church’s Biblical view of family life and human sexuality, are not part of the LCWR agenda in a way that promotes Church teaching.