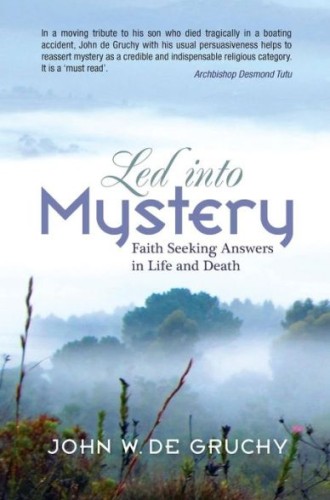

Led into Mystery, by John W. de Gruchy

When a life-splintering phone call stops the world and drains the sky of all its light, how can comforting words be anything but confabulation, anything but fantasy and illusion?

In Led into Mystery, John W. de Gruchy addresses this question from the standpoint of his own grief as well as his theological sophistication. A South African well known for Bonhoeffer scholarship and for work on restorative justice and Christian humanism, de Gruchy reveals that his eldest son, Steve, himself a husband, father, and theologian, “tragically died in a river accident” early in 2010. The father writes that on first seeing where his son’s still unrecovered body had disappeared beneath the water, he was “inconsolable. I do not know how long I sat there and wept.”

The story is wrenching. Any heart—not least a pastor’s—quakes to hear it. And it tosses up, besides our sympathy, a cloud of anxiety and doubt. Such a loss could put anyone on the doorstep of despair.

De Gruchy intends his book for people who have hovered between faith and doubt. Knowing that human insecurities beget comforting illusions, he wants to offer an account of Christian hope that has both biblical and scientific integrity. He disavows fundamentalism yet affirms the substance (as he sees it) of the Bible story. He detects blinkered arrogance in some versions of scientific orthodoxy, but still aligns himself with the scientific spirit and the consensus that has sprung from it.

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

The book’s title pinpoints its unifying theme. Faith leads us into mystery. When deeply considered, our scientific investigations as well as our hopes give rise to awe, wonder, and humility, and to dissatisfaction with the premise that everything can be explained.

The New Testament’s accounts of Jesus and of the postresurrection flourishing of the church underscore the real plausibility, de Gruchy argues, of our dreams for human betterment and for reunion with those we lose to death. Grief may sharpen such intimations of transcendence, but the truly alert cannot escape modernity’s doubt, its suspicion that the human story bends toward brute nothingness, toward an ending that lacks all consolation. If we are at once honest and fully alive, we are caught in mystery. De Gruchy quotes Einstein’s remark that the person who is a “stranger” to mystery is “as good as dead: his eyes are closed.”

De Gruchy believes that he is offering a description of the way things are. Secular arrogance and self-satisfaction are as misbegotten as the arrogance and self-satisfaction of religious fundamentalism. Nothing we know entails a reduction of all things to heartless chance. And arresting human experiences—he mentions a nonreligious calligrapher friend who makes an illuminated Bible for St. John’s Abbey in Minnesota—do sometimes pull the subjects of those experiences into communion with something deeper than the ordinary. The Bible writers, themselves fully in touch with questions raised by suffering, offer stories that call forth “the recurring ‘nevertheless’ of faith, hope and love.” Though their witness may derive from fear and disappointment, it may also point to grace. Unless you stipulate, against all the signals of mystery, that the world is a closed system admitting of nothing so new as resurrection, the possibility of underlying grace seems plausible enough for fully responsible religious faith.

The occasion for de Gruchy’s writing of this book was not only grief but also hope—his hope in the face of his son’s death. De Gruchy remarks that during the struggle against apartheid, the problem behind church division on the matter was eschatology. Many Christians in South Africa had forgotten that Christian hope is about more than deliverance from death; it is about God’s justice on earth as in heaven. True Christian hope is resistance against a present that no one—certainly no one who attends mindfully to scripture—can accept; it is, in Jürgen Moltmann’s words, refusal to “put up with reality as it is.” A responsible faith thus involves responsible hope. It says yes to this life and this earth, yes to full-hearted engagement with the problems and possibilities of today.

All of this belongs to the “ultimate concern” that true faith embraces. Underscoring that faith is a way of life, de Gruchy reminds readers that it is “not the acceptance of a doctrine, but a commitment to God . . . and all that this implies.” He might better have said that faith is not mere acceptance of doctrine. His own book shows how doctrines, or teachings, are premises for action and aspiration. And whether they go wrong or—as in this beautiful book—go right makes an enormous difference.