Playing God, by Andy Crouch

Playing God is the exercise of power, and power is good. Power is a gift, a means of peacemaking, a God-sanctioned key to human flourishing.

This is the striking claim advanced in Andy Crouch’s insightful and engaging book Playing God. Crouch, the executive editor of Christianity Today, presents here an evangelical take on the Christian social ethic, offering criticism as well as affirmation of the movement in which he now plays a leading role. His argument says yes to power—he declares that the idea that Jesus “gave up” power is dead wrong—but he also addresses “idolatrous power,” the distortion that seizes advantage over others by means that can descend into brutality.

Lord Acton said that power “tends to corrupt, and absolute power corrupts absolutely.” Crouch demurs, not dismissing the point altogether but saying that human well-being depends on generous employment of power. Distorted power is corrupt and corrupting, but not all power is distorted. True power is creative ability in the service of “comprehensive flourishing”; it is power exerted in the spirit of Christ, the “trustworthy image” of God. A focus on the “dark underbelly of domination” in human relationships may shed important light, but power can be redemptive, too. True power is creation, not compulsion. Instead of making winners and losers, it creates room “for more power”—more opportunity, that is, for more people to build abundance and blessedness on earth. Power as aggression is deadly; power that bears the image of God is life-giving.

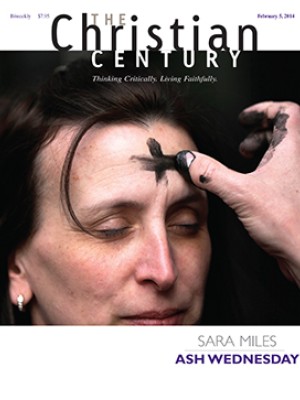

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

Crouch wants readers to realize that responsibility before God requires passionate embrace of power. Neglect of power—whether because of disinterest, laziness or cynicism—is a spurning of the divine call. If God’s ultimate end is shalom, comprehensive human flourishing, then those who bear God’s image must throw off passivity and engage the joys and pains of creative effort on behalf of human betterment.

Here Crouch’s criticism of his own evangelical tradition comes into play. When telling the Christian story, evangelicals too often begin with the Fall and end with Satan being cast into the lake of fire. But this abbreviates the story and reduces the good news to escaping from the world. A “divine skyhook” takes the place of divine empowerment for renewal and creativity.

One of the book’s major sections is on institutions and creative power. Crouch explains that institutions organize human activity and enhance our capacity to get things done; they “create and distribute power” and are thus “essential.” At the cross Christ disarmed those institutions (“principalities and powers,” “rulers and authorities”) that pervert and exploit, but the point was to clear the way for better institutions. In making this case, Crouch sees another reason to criticize evangelicalism, which has too often focused on personal relationships without attending sufficiently to institutional or structural renewal.

Christians, Crouch contends, should embrace true power and use it as effectively as possible for God’s purposes. We must be “trustees,” vigorously guarding against cynicism and abuse of power, eager to take part in the renewal of institutional life, inside our churches and outside of them.

Crouch applies this way of thinking about embrace of power to a discussion of how Christians might deal constructively with issues like abortion and excessive incarceration rates. He defends evangelism even as he urges work for justice and peace. He also acknowledges the link between Christian teaching about power and questions of warfare and the military. But in this case he holds back. He mentions the debate between the Augustinian and Anabaptist traditions with respect to the use of force, only to say that because this territory is so “well-traveled,” he will not “retrace” it now. But a book on the Christian use of power certainly ought to weigh in on violence.

Overall, however, readers will find plenty of insight and inspiration here. As a journalist, Crouch places high value on clarity of style and usefulness for everyday life. He brings in stories from his personal life and from popular culture that sustain interest and shed important light. And he illuminates his theme through multipage explorations of key biblical passages, which will be helpful to readers with preaching responsibilities. Crouch’s evangelical perspective bears provocatively on a conversation pertinent to everyone.