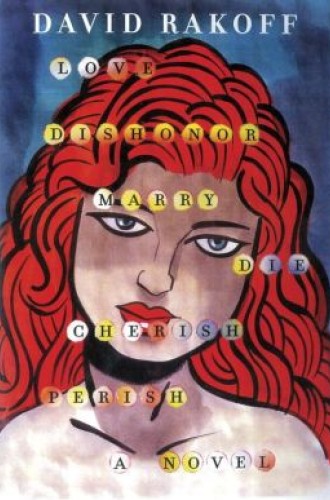

Love, Dishonor, Marry, Die, Cherish, Perish, by David Rakoff

There are a number of ways in which this novel by David Rakoff could be written off as cliché. (Read “a novel by” aloud. The phrase completes the rhyme and rhythm—anapestic tetrameter—of the six-word title.) First, and most obviously, the entire posthumously published novel is written in rhyming couplets—a style used without irony these days only in greeting cards and pop lyrics. Second, and less obviously, a vision of a woman’s beauty stands at the novel’s thematic center. But Rakoff was master enough of his craft that his rhymes lapse into doggerel only when he chose: in a character’s tacky wedding toast, for example. His characters manage to be archetypes that are plausibly, endearingly human.

Those already familiar with Rakoff’s work—his three volumes of essays, Fraud, Don’t Get Too Comfortable and Half Empty, as well as his contributions to the radio program This American Life—will recognize his distinctive wit, his melancholy and his belief in the redemptive power of kindness. In the final chapter of Half Empty, he recounts some of the things that friends said to him when he was diagnosed with the sarcoma that eventually killed him (including “an unedited, ‘Oh my God, that’s so depressing’”). He said that even in such awkward moments, “people are really trying their best. Just like being happy and sad, you will find yourself on both sides of the equation many times over your lifetime, either saying or hearing the wrong thing. Let’s all give each other a pass, shall we?”

This gentleness pervades the novel, which spans a century of American life in vivid if brief episodes (the entire book, including artist and designer Chip Kidd’s marvelous illustrations, is fewer than 130 pages) in which characters are linked to each other and either fortified or nearly destroyed by acts of kindness or cruelty. Where they are nearly destroyed, they are restored and redeemed—or at least consoled—by beauty.