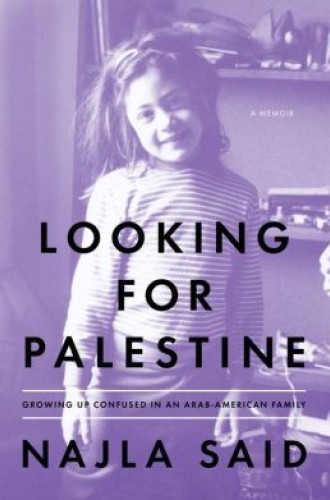

Looking for Palestine, by Najla Said

Najla Said has had every reason to be confused. She explains in the opening lines of her memoir: “I am a Palestinian-Lebanese-American Christian woman, but I grew up as a Jew in New York City. I began my life, however, as a WASP.”

Najla Said is the daughter of the famous literary critic Edward Said, whose book Orientalism contributed in the 1970s and 1980s to changing the way we think about, talk about and claim identity in American society. Edward Said noted that Western society, literature, culture and politics have tended to make vast generalizations about the East, viewing a mysterious and exotic but dehumanized “Orient” through its own warped lens. In part because of Said’s work, Americans started to say “Chinese-American” or “Arab-American” instead of “Oriental.” We started to rethink the melting-pot premise of previous generations and to grapple in greater depth with what it means to be a diverse society.

But the nuances of Orientalism did not make Najla’s struggle for identity any easier. Religion was one of many sticking points for her in forming a coherent identity. Najla’s parents were both secular humanists with little interest in religious labeling. Najla, however, was baptized an Episcopalian as a baby. When she asked her mother why, she explained, “Your grandmother insisted. . . . I agreed so she wouldn’t get upset. It was only water on your head, so I didn’t mind.”