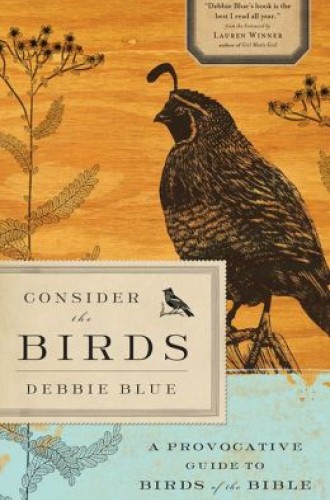

Consider the Birds, by Debbie Blue

Like Lauren Winner, who admits in the foreword to Consider the Birds that she is “not really interested in birds at all,” I’m not especially enamored of feathered creatures. It’s not that I revile them, but I have perhaps been shat upon once too many times. I am, however, a fan of Debbie Blue, one of the founding pastors of House of Mercy in St. Paul, Minnesota. Blue’s first two books, Sensual Orthodoxy (homiletics) and From Stone to Living Word (hermeneutics), are on my short list of books I consider life changing. Which is to say I’ll read whatever the good Reverend Blue wishes to write about. Vultures and sparrows and quail? So be it.

Consider the Birds is, as the subtitle promises, a provocative guide to birds of the Bible. And it is excellent: observant, exhaustive and often extremely funny. One passage begins with an exaltation of the beauty of birds. “You couldn’t make up the peacock,” Blue gushes. “If you were going to create a wonderland, of course you would put bright colors that fly into the sky. They are like abstract paintings that sing. And lay eggs.” In her next breath she presents a bird of a different feather:

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

New World vultures projectile-vomit into the face of anything that startles them. They eat excrement (especially human) and dead bodies. They defecate over their own legs. Most vultures are bald. This allows them to stick their entire heads inside a carcass without feathers to foul with blood and rotting flesh. A turkey vulture has very large and obvious nostrils. It is possible to see through from one side of its head to the other. This is not pretty. It’s weird and scary.

I repent of my indifference: birds are utterly fascinating.

Blue conveys a remarkable amount of information about avian life forms. Did you know that ostrich thighs are eerily similar to human legs? That a griffon vulture once collided with a commercial airliner at an altitude of 37,900 feet? That sparrows are the bullies of the bird world, reviled by most serious birders on account of their tendency to kill bluebirds and steal their shelter? I did not. Neither did I know many of the religious, historical and literary allusions to birds that Blue weaves into her essays. The multiplicity of bird species and the multivalence of birds in human culture afforded Blue a vast amount of material with which to work. And although the ten birds she highlights—pigeons, pelicans, quail, vultures, eagles, ostriches, sparrows, roosters, hens and ravens—are indeed “of the Bible,” Blue did not merely pluck the hen and its sister species from the pages of scripture and craft vaguely spiritual essays about them. Biblical theology and interpretation are every bit as central to the book as the birds themselves.

Yet Consider the Birds is not fundamentally about the Bible or about birds. It is about us. It is fitting that one might consider humanity when purportedly considering the birds: Jesus pointed to the ravens to illuminate something about people—namely, the depth of our insecurity—and to remind us how much more God cares for and loves us. The book is rich with observations about human behavior and culture. This excellent work of theological ornithology is even more compelling as a work of theological anthropology.

In the chapter about ostriches, Blue riffs on the biblical scholar Abigail Pelham’s thesis that the book of Job is not a tragedy, as commonly presumed, but a comedy. As his luxe and self-important life is upended, Job becomes a “companion of ostriches”—a laughable fool. Blue and Pelham laugh not at Job’s fall from glory but at the “incessant narcissism at the heart of the human condition.” Blue ponders:

For all our bluster and all our desire for grandiosity and significance, we are in fact animals: large-brained primates with a tragic-comic capacity for a sometimes overwrought self-consciousness. . . . We think we are kings or queens, masters of the universe or at least our own destiny. We forget that a foot may crush us, or that the wind may knock us down. We are not in control.

Job’s demise removes him from what he believed to be his rightful place at the top of the world—or rather, the center of the universe. God’s humbling speech from the whirlwind, according to Blue, is essentially God saying, “Look, stop focusing on yourself for a minute—look at it all. It’s so beautiful and mysterious and complex—and bigger than you, way bigger than you.” As for the ostrich—so often maligned as stupid and laughable—Blue points out the presumption in mocking a species that has been around far longer than our own.

It becomes clear that our appraisals of birds reveal more about us than about them. Why do we dislike pigeons but glorify doves, which are actually pigeons? Why do we obsess over the brute power of the eagle, slapping them on our national flags and tattooing them on our biceps? Why do men—and far more rarely women—enjoy watching roosters tear one another’s eyes out in cockfighting rings throughout the world? Blue’s assessment of humankind (both as individuals and as cultures) is depressing. We despise vulnerability, in ourselves and others. We are wracked by anxiety and prone to competition. Like the raven we are ravenous, often more driven by our appetites for food, sex and attention than guided by our better angels. Viewed from the perspective of our feathered friends, we are an invasive and murderous species. We destroy their habitats. We raise them in inhumane conditions for cheap protein. And sometimes we simply shoot them for fun.

Blue’s theological anthropology might be depressing, but it is also refreshingly biblical. All the terrible things we do are right there in the text. Yet just as Blue deftly coaxes the reader to imagine the redemption of the ugly and unlovable vulture, we can believe that even ugly and unlovable humanity can be redeemed by the God who made and loves us all.