Israel’s Protestant friends

On a warm summer day in Bay City, Michigan, my mother summoned me from a neighborhood baseball game to the front door of the forlorn parsonage on South DeWitt Street. “This is it,” she said urgently. It was June 1967, and Israel had just taken the ancient city of Jerusalem, including the Wailing Wall. My father, an evangelical minister, preached on the book of Revelation more than any other text, especially in his Sunday evening sermons, so I understood the stakes. If the Six-Day War did indeed signal the end-times, as my mother fervently believed, Jesus would return to collect the faithful in an event we called the Rapture, and the apocalyptic prophecies outlined in Revelation would unfold in rapid succession.

Although my mother now denies the incident (and I here duly record her dissent), the exchange is seared in my memory. Even at 12 years old, I understood the significance of Israel to the end-times. The formation of the state of Israel in 1948 had been a direct fulfillment of biblical prophecy, and Israel’s military success in 1967 made Israeli borders almost coterminous to those on the maps in the back of my King James Bible.

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

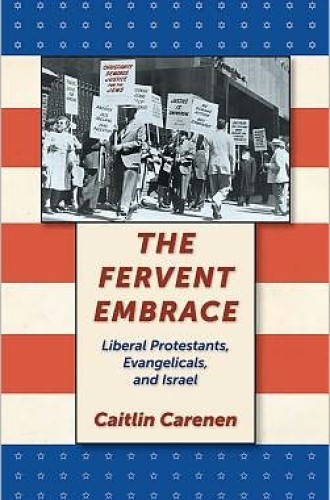

The Six-Day War, as Caitlin Carenen argues in The Fervent Embrace: Liberal Protestants, Evangelicals, and Israel, represented a turning point in American Protestant views of Israel. Before World War II, Americans were largely indifferent to the plight of Jews; editors of the Christian Century even encouraged Jews to celebrate Christmas. But the horrors of the Holocaust prompted a rethinking on the part of both mainline and evangelical Protestants. The former, motivated by humanitarian concerns, lobbied the government for sympathetic policies toward the Jews. When Israel declared itself a state on May 14, 1948, President Harry Truman extended diplomatic recognition within minutes.

In the middle decades of the 20th century, several organizations battled one another for the hearts and minds of liberal Protestants. The American Christian Palestine Committee and Christians Concerned for Israel lined up with Zionism, while the American Friends of the Middle East expressed concern for the Arab refugees and criticized Israel’s expansion into Palestinian territory. The doctrine at issue was supersessionism, the idea that the church had inherited the promises made to ancient Israel, a conviction that liberal Protestants eventually abandoned. At the same time, the government of Israel cultivated the good will of American Protestants by inviting religious leaders to visit—and paying their expenses.

Although such efforts initially paid off, mainline Protestants began to cool in their attitudes toward Israel, given the cumulative effects of “illegal settlements on the West Bank and Gaza, the continuing plight of refugees, and the cause of Palestinian statehood.” The Six-Day War confirmed their worst fears about Israel’s imperial ambitions.

On the opposite side of the Protestant spectrum, evangelicals began to emerge as Israel’s best friend—somewhat, I imagine, to the puzzlement of Israelis themselves. Although mainline Protestants had backed away from missionary efforts to the Jews (a continuation of a trend begun by the Hocking Report of 1932), evangelicals began to display more interest in evangelizing the Jews because of their understanding that the conversion of Jews to Christianity was an essential precondition for the unfolding of biblical prophecies. The best friends of Israel, paradoxically, were anti-Semitic from the perspective of Judaism.

Marc Tanenbaum of the American Jewish Committee was one of many Jewish leaders to notice the shift. “The evangelical community is the largest and fastest growing block [sic] of pro-Israeli, pro-Jewish sentiment in this country,” he said. “Since the 1967 War, the Jewish community has felt abandoned by Protestants, by groups clustered around the National Council of Churches.” Improbably, and at cross-purposes with Judaism itself, evangelicals had rushed in to fill the vacuum.

This realignment, Carenen points out, roughly tracked American popular sentiment. Mainline Protestant leaders’ apparent sympathy with the Palestinians further alienated them from the views of the majority of Americans—57 percent during the 1980s—who supported Israel. By the end of the 1980s, Carenen writes, “the Christian Zionist ideology represented mainstream American Protestantism,” and when Menachem Begin bombed an Iraqi nuclear reactor in 1981, she claims that the Israeli prime minister’s first phone call to the United States was to Jerry Falwell, not Ronald Reagan. The National Council of Churches condemned the attack.

Carenen tells this complex story of shifting Protestant allegiances evenhandedly and, more often than not, with clarity, though it is easy at times to get lost in the various acronyms. She is especially thorough in her survey of mainline Protestants. But her contention that U.S. support for Israel was one of the central concerns animating the religious right in the late 1970s is less persuasive. “Willing to ignore Carter’s outspoken faith in favor of hard-right Israeli interests,” Carenen writes, “Falwell urged his followers to support Ronald Reagan’s campaign.” Yes, Falwell listed support for Israel among the founding principles of the Moral Majority, along with traditional marriage, a strong defense and opposition to abortion, but none of those issues served as the catalyst for the religious right.

They did reflect popular evangelical concerns, however, and therein lies the genius of evangelicalism and the religious right—a willingness to invoke popular sentiments for theological or political ends. But evangelicals did so at a price. As Carenen points out, they “undertook their own theological innovations through a deemphasis on end-of-times eschatology to focus more on the command to bless Israel in order to garner blessings for the United States.”

For their part, the defenders of Israel were willing to accept support from any quarter, even though it made for strange bedfellows. As Lenny Ben-David, formerly associated with the Israeli embassy in Washington, once declared, “until I see Jesus coming over the hill, I am in favor of all the friends Israel can get.”