The zombie war

Christ promised a resurrection of the dead. I’m not sure this is what he had in mind.” So marvels one of the characters in The Walking Dead, a zombie-apocalypse survival story on AMC which recently began its third season (seasons one and two are available on Netflix). The show has drawn raves for its facility with horror, its explorations of leadership and its unexpected twists on a familiar genre.

Zombies are by now standard entertainment. Dawn of the Dead (2004) parodied zombies by showing them walking aimlessly through shopping malls accompanied by Muzak: “zombies r us.” Shaun of the Dead (also 2004—a big year for the undead) skewered hipsters by portraying them arguing in deadpan over which vinyl records to hurl uselessly at the monsters. In 28 Days Later zombies move terrifyingly fast. Max Brooks’s 2006 novel World War Z: An Oral History of the Zombie War is set to become a blockbuster movie starring Brad Pitt.

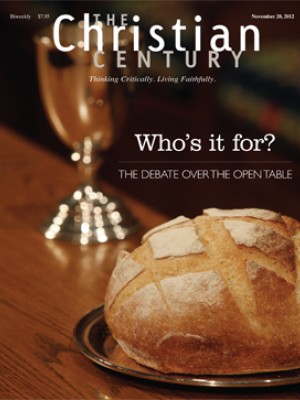

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

TWD is good enough to have drawn 10.9 million viewers for its season three premiere—the most ever for a basic cable drama telecast (or so claims its Wikipedia page). In a breakoff series called Talking Dead, guests including celebrity fans break down the just-viewed episodes like retired football stars dissecting plays in the NFL. The zombie apocalypse may not be upon us, but the undead are gobbling up the TV channels.

Season one opens with Rick Grimes (played by a Brit, Andrew Lincoln, with a perfect Georgia drawl) as a small town cop who awakes from a coma. During his slumber the world was taken over by flesh-eating undead hordes. His family is gone, piles of bodies surround the hospital, and military paraphernalia is stacked in the streets. Locked inside the hospital cafeteria are moaning, long-fingered zombies known as “walkers.” Rick heads for Atlanta and the Centers for Disease Control. Improbably, he meets up with his wife, Lori, and son and his best friend, Shane Walsh. Assuming that Rick is dead, Lori (Sarah Wayne Callies) and Shane (Jon Bernthal) have shacked up. Rick and Shane joust not only over Lori, but over who’s in charge and who best can keep the others safe. They and a dozen or so others form the nucleus of a group that tries to survive the walkers, scrounging for food, fuel, shelter and ammunition.

The walkers are the real stars of the show. They’re also terrifying as they swarm and bite and tear at the protagonists. Anyone bitten dies and rises to become one of them. This is all usual zombie fare. What’s new here is the theme of facing loved ones who have become one of the undead. Do you shoot them and let them die for real? Or is it more compassionate to let them alone, maybe in hopes of finding a cure?

The show is especially concerned with the fate of children. One episode opens with Grimes approaching a child from behind, reassuring her, “Little girl, it’s OK, I’m a police officer.” When she turns around, she is missing half a face. He scowls and shoots her. No music accompanies the scene, and it is shot in sepia tones, befitting the graphic comic that inspired it. A major concern is the fate of Grimes’s son, Carl. As the show develops, people start being resurrected without being bitten. “We all have it,” Grimes surmises—it being the zombie virus.

The relationships between the apocalypse survivors are the focus of this slightly soapy (she said what? To whom?!) series. Moments of tenderness, friendship and even love break out. The characters battle their own racism and sexism as they try to determine how to make decisions in a world gone to hell. In this new world, the racist bow hunter with tracking skills is suddenly really helpful; the African-American hipster from Atlanta, while far more sympathetic as a person, not so much. The bleeding heart 1960s liberal who can fix an RV: helpful. The civil rights lawyer: not at all (until she learns to shoot).

One problem with zombie stories is there’s no way for them to end well. TWD seems headed somewhere dark, with visions of a prison hinted at in the conclusion to season two (imagine a world in which the inside of a maximum security facility is desirable).

What do we make of these walkers? Do they conjure up those church members who are not-alive and not-dead, moaning for the flesh of their pastors? Or clergy who’ve lost the light of a calling and are already rotting?

Whatever else zombies are, they’re a parody of Christian hope for the resurrection of the body. In her book Stiff: The Curious Lives of Human Cadavers, Mary Roach describes dead bodies as not so much terrifying as sad—they were once animated and squishy and alive, but not any more. Zombies remind us that the weirdest, wildest Christian hope is that our bodies will be reanimated one day—and become as alive as Jesus on Easter morn.