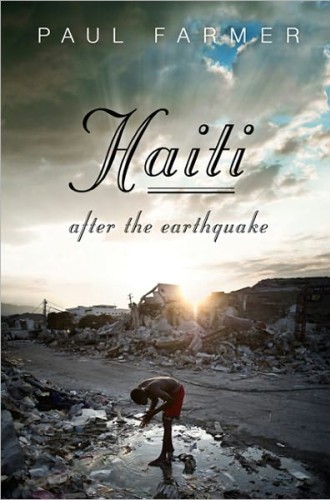

Aftershocks

Paul Farmer has a keen sense of the widespread tendency to portray Haitians as helpless victims. That is well evident in this poignant chronicle of the year that began with the January 12, 2010, earthquake and ended with commemorations in Haiti marking the event—which were often sad, empty affairs. It seemed at that time as if an opportunity had been lost and Haiti was once again falling into old patterns, and as if the world was already neglecting a country that a year earlier had received an outpouring of international compassion, what Farmer calls "a tsunami of generosity."

Farmer, a Harvard professor and a physician with longtime experience in Haiti, is UN deputy special envoy for Haiti under former president Bill Clinton (he admits he is not as comfortable in the public spotlight as his "indefatigable" boss). He writes that most of the ceremonies of the January 12, 2011, anniversary "went by in a haze." He recalls not feeling particularly "prayerful" and reports that he retreated to a Haitian friend's home in Port-au-Prince "to contemplate the year quietly and alone."

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

It is telling that Farmer, a cofounder of the respected humanitarian organization Partners in Health, uses the word haze because much of this world-weary book—part memoir, part useful (if somewhat dispassionate) explanation of the complexities of humanitarian work in Haiti—has the somber, funereal tone of someone still traumatized. I don't mean that as a criticism. It's hard not to admire Farmer, who works at the highest international policy levels; commutes between Port-au-Prince, New York, Boston and his home in Rwanda; and does his best to see that humanitarian assistance does right by Haiti while he mourns Haitian and non-Haitian colleagues and friends who perished in the quake.

The shock of the earthquake for someone who has spent years trying to improve the quality of Haiti's health-care system registers early in the book, in a somber but beautifully penned passage in which Farmer recalls landing in Port-au-Prince soon after the quake. He says that he "never arrived with a heavier heart than on that day":

As soon as we opened the door, it hit us: a charnel-house stench filled the air of the windswept runway. I knew this smell but never imagined I would encounter it in an open space. Now it hung over the city like a filthy, clinging garment—the stench of a battlefield without the violence or din of war. Except for airplanes and helicopters, there was silence.

Farmer laments that the Haitian people have long been "excluded from any meaningful discussion of their fate"—a dynamic that seems to be continuing among international policy makers since the quake. (Farmer praises Secretary of State Hillary Clinton as a notable exception.) Haitians grieve "the inability of state and non-state providers to provide basic succor to those in great need, in spite of the large presence of humanitarians and NGOs," Farmer writes. "These sentiments—these complaints—have been the constant companions of almost everyone working in Haiti to deliver such services."

The expression of such frustration betrays a physical and psychical exhaustion that eventually catches up with many Haitian and non-Haitian humanitarian workers. Farmer writes of savoring the hopeful moment of a hospital groundbreaking, only—"as ever in Haiti"—to have the moment "crowded out by anxiety and even dread: anxiety, for many of us, about how we were going to run such a hospital once it was built, and dread because a new epidemic, long feared, was about to hit Haiti." (Farmer is referring to a cholera epidemic that slowed recovery efforts in late 2010 and is still doing great harm.)

Yet Farmer's exhaustion might also be due to something else, and Farmer hints at it once or twice. Perhaps he is not fully comfortable in, or suited to, the role of policy insider.

Haiti after the Earthquake is as good an introductory book as any to the complexities of Haiti. It contains a nimble explanation of the historical roots of Haiti's troubles, as well as supplemental contributions by colleagues and friends such as the Haitian-American novelist Edwidge Danticat. But with its "insider asides" it sometimes seems like too careful and cautious a book. I missed some of Farmer's old fire, displayed in The Uses of Haiti, in which he takes on pernicious U.S. policies toward Haiti, including those implemented while Bill Clinton was president, and in Pathologies of Power, his eloquent affirmation of medical ethics and human rights.

Farmer has not given up on Haiti or the idea that Haitians need to control their own destiny. He makes clear that a key factor in Haiti's success will be fashioning a state that provides things like a functioning health system. After all, he writes, "what institutions confer the right to health care? Not NGOs, universities, or patients and their families; not aid agencies or the UN. The government confers rights." Farmer soundly quotes Franklin D. Roosevelt on this score: "Public health . . . is a responsibility of the state as [is] the duty to promote general welfare. The state educates its children. Why not keep them well?"

One thing is clear above all, Farmer argues: "Until the basic needs of the Haitian majority are met—food and shelter, education and health care, jobs that promote dignity—there will be scant peace in Haiti. This was true before the quake, and it remains so after."