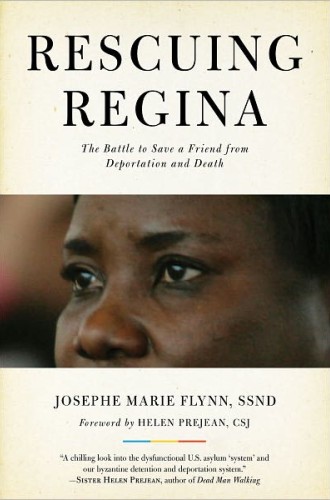

Rescuing Regina, by Josephe Marie Flynn

This book should be made into a movie. As a book, the story has several strikes against it. The central character is not well known outside Milwaukee. The author, a 70-year-old nun, has written no other books. The cover is not sexy. And, heaven help us, it's a book about social justice and human rights—topics that market-driven book publishers rarely touch. Be honest: would you buy a book whose subtitle is The Battle to Save a Friend from Deportation and Death?

On the other hand, how would you feel about going to see a legal thriller that features political chaos, rape, torture and daring escapes, as well as a tender romance, miraculous interventions and really cute children? And suppose this story has a David-and-Goliath theme, in which the (incidentally gorgeous female) protagonist and her friends come up against brutal African rulers and hostile American bureaucrats—and win? Imagine this movie scene:

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

A quiet street in a humble Milwaukee neighborhood. Late March, 6:30 in the evening, dusk. Patches of dirty snow dot the yards. Families have turned on their lights; some have drawn their shades. Zoom in on one tiny bungalow, where three armed men wearing police vests are pounding on the front door.

The door opens a crack and two of the men push their way in. The man who stays outside hears shouting, banging, children crying. He looks at his watch. A woman screams. Soon the two men reappear, bringing a woman in pajamas and slippers with them. Children continue to wail as the men and the woman get into an unmarked car and drive away.

The woman is Regina—young, beautiful, Congolese. In her homeland in the early 1990s, she responded to her country's political unrest by working with a prodemocracy group. In 1994, just a few weeks after her marriage to another activist, David Bakala, soldiers disrupted a meeting where she was speaking, tied her up, viciously beat and kicked her, raped her and then marched her to a women's prison. For three months she lived with three other women in a small windowless room.

Once released, Regina was afraid to return home. She feared that David would reject her: in their culture, rape brings dishonor not on the rapist but on the woman and her family. David, however, welcomed her back, and she resumed her political work. And then, nine months after the gang rape, she was raped again. Friends persuaded her that if she stayed in Congo, she would surely be killed. Without telling David, Regina procured a false passport, put a few personal items in a duffle bag and entrusted herself to a fisherman who propelled her through fog and rapids down the Congo River. It was the first stage of her journey to America—home of democracy, land of the free.

But being an asylum seeker in the United States was less promising than she anticipated. Never mind the gratuitous strip search she underwent upon landing at JFK Airport in New York City. The more serious problem was the U.S. immigration system's approach to "the huddled masses yearning to breathe free":

Put Regina, a non-English-speaking rape survivor fearing for her life, into a complex immigration process involving an adversarial, one-time-only hearing with a judge who has life-or-death authority over her. Start with well-meaning advice from people who don't know the system. Toss in a student translator, an overworked lawyer (make that three, none of whom listened to her story nor checked translations), a shrewd government attorney, and a flustered courtroom translator. Give her no preparation, which of course will kick her into posttraumatic stress. Then call her a liar.

Year after year, Regina persisted. In 1997 she was miraculously reunited with David, who had been captured, imprisoned, tortured, condemned to death—then suddenly spirited out of Congo, with strict orders never to return. He too applied for asylum, and he too ran into difficulties. But by 2000 the two of them thought they were here to stay. Now parents of a baby daughter, they moved from North Carolina to Milwaukee, joined a parish, found work, bought a house, made friends, had a son.

And then on March 22, 2005, with no warning, comes the knock on the door, an unauthorized search, threats, bullying—and Regina is whisked off to an American jail, her children's screams ringing in her ears.

If Rescuing Regina were a movie, it could court adolescent males by featuring explosions, battles, ghoulish torture and harrowing chase scenes. Or it could attract art-film buffs as a psychological study of two strong, intelligent, good people breaking down as they undergo persecution, posttraumatic stress disorder and America's Kafkaesque immigration system. But for broader appeal, it might focus on the two-year-long effort of a determined nun and a tenacious lawyer, backed by thousands of concerned Milwaukee citizens—Democrats and Republicans together—to save Regina from certain deportation and death. On the one hand, a courtroom drama, seemingly insuperable obstacles, the power of the state. On the other, courage, persistence, the power of love—and enough suspense to keep you on the edge of your chair from beginning to end.

But Rescuing Regina is a book, not a movie, and that gives the author space to inform as well as entertain. Sister Josephe Marie Flynn had no interest in political activism until she met Regina and began learning what happens to people who seek asylum in the U.S. She learned, for example, that on any given day in 2005 the U.S. was holding 22,000 immigrant detainees (the figure for 2010 was over 33,000). Most of these prisoners, like Regina, are not criminals. Many are torn from their children. None are given the legal rights available to any U.S. citizen and required by international law, and many will be murdered if they are returned to their home countries. Yet they continue to be locked up in private, for-profit prisons "with no enforceable national standards" and operators who are "eager to maximize income and minimize costs." Despite allegations of "sexual abuse, physical violence, medical neglect and mismanagement" in these prisons, lucrative government contracts continue to be awarded to them.

With no movie in sight, you'll need to read the book to find out what happened once Sister Josephe began working for Regina's release. Fortunately it reads like a novel even as it raises troubling questions of social justice.