The Long Goodbye, by Meghan O’Rourke

The Long Goodbye is poet Meghan O'Rourke's account of her mother's colorectal cancer and the year of mourning that followed her death. I read the book the first time through as a companion—O'Rourke's experience is eerily like my own. The second time through, I read it thinking of the church—what we in the church might take from this exploration of dying, death and bereavement. It is a book the church should read.

O'Rourke's description of the emotional topography of caregiving is brave and truthful. There is plenty of straightforward filial love here, but there is also frustration, anger and jealousy of the hospital nurses to whom her mother was so consistently kind. O'Rourke also considers her own relationship with mortality. She was made mortal by her mother's dying. She came to realize something about her own finitude—but what she mostly realized is that she cannot fully grasp her own eventual death. This is one of the odd fruits of a parent's death, a spouse's death: you are given "the knowledge that we die." You want to reshape your life around that awareness, but you can't, not consistently. You are now mortal, but only sporadically so. Pondering La Rochefoucauld's injunction that death, like the sun, is not to be looked at directly, O'Rourke puts the matter plainly: "Mother, I am confronting yours, here, as I write. But I have not come to terms with my own."

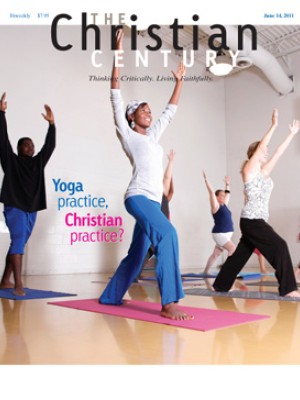

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

O'Rourke also offers great insight into mourning. Our society, she notes, has forgotten how to mourn and how to respond to mourners. In the days after her mother's death, O'Rourke "felt the lack of rituals to shape and support my loss. . . . I did not know what I was supposed to do, nor, it seemed, did my friends and colleagues." O'Rourke and her family are not religious, yet they would not likely have encountered more robust ritual had they been devout Christians. The church sometimes ritualizes burial well, but we pay less attention to what often precedes death (long-term illness) and what follows it (bereavement).

Throughout her bereavement, O'Rourke longed for something do to with her grief:

I kept thinking, "I just want somewhere to put my grief." I was imagining a vessel for it: a long, shallow, wooden bowl, irregularly shaped. I had the sense that if I could chant, or rend my clothes, or tear my hair, I could, in effect, create that vessel in the world.

But there was no ritual, and "without ritual, the only way to share a loss was to talk about it." Talk, of course, is awkward, and often beside the point. No one--neither the mourner nor the mourner's friends—knows quite what to say. (As O'Rourke's father observed, acquaintances ask, "How are you?" The words are well intentioned, but they "shouldn't always be taken for an actual inquiry.") Which is precisely why we need ritual. Ritual gives us a script.

O'Rourke reminds us that in previous eras, mourners were sustained by a robust protocol: laying out the dead at home, donning mourning jewelry, observing a calendar of bereavement that meant a mourner wasn't expected to socialize with her usual gusto. Now those protocols are gone, abandoned in the interest of helping people get over their loss efficiently. When, five days after her mother's death, O'Rourke was rudely pushed by a man on the subway, she wanted mourning clothes. Had she been clad in a black dress and a black veil, the man would have known she was bereaved, and he would have treated her more gently.

We should read O'Rourke for her insights into emotion and ritual, and we should read The Long Goodbye for the melancholy enjoyment of O'Rourke's prose. Reading it is like reading a memoir by Patricia Hampl: you know you are in the hands of someone whose first words are poems. When O'Rourke's mother, newly diagnosed with a tumor, said that the doctors "don't know what it means," O'Rourke felt "hopeful, as if the tumor were something that could be interpreted, like a passage in Shakespeare." And here is O'Rourke recalling the day her father dressed up and attended his grandmother's funeral: "I thought he looked like a figurine of himself." Consistently, O'Rourke pays a poet's attention to words: "Unmothered is not a word in my dictionary, but I often find myself thinking it should be. The real word most like it . . . is unmoored." The book is filled with sentences like that, sentences that stop you with their economy and emotional heft. The last three sentences of The Long Goodbye are especially unforgettable. Their rhythm will replay in your head long after you close the book. I won't quote them—you will just have to read them yourself, and don't skip ahead and peek.