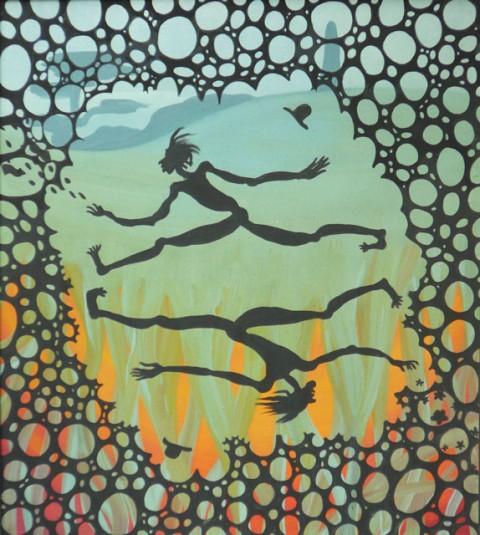

All is vanity

When Don Meredith, the Dallas Cowboys quarterback who became a well-known commentator on Monday Night Football, died last year, an obituary ended its account of what seems to have been an enviably full and varied life by quoting a comment he made to Sports Illustrated: "My deepest fear is that one day I'm going to find out that this is all there is to life, and it won't be enough."

Meredith voiced a sentiment sounded again and again by a biblical character known only by his title, Qoheleth (hereafter, Q), a man whose quoted words make up most of the book of Ecclesiastes (hereafter, E). He is a man who has undertaken to find out what there is to life, and whether—in the form of wealth, pleasure or the pursuit of wisdom—it will be enough. The question, in other words, "What is the point of it all?" or "What does it all add up to?"

"I applied my mind to seek and to search out by wisdom all that is done under heaven," he writes, and concludes, "It is an unhappy business that God has given to humankind to be busy with" (1:13). Repeatedly, after some specific experience or observation, he concludes, "this also is vanity [hevel]." So he frames the results of his search with the question (1:3), "What do people gain [Hebrew yitron; Greek perisseia] from all the toil ['amal] at which they toil under the sun?"—where yitron, like perisseia, means "surplus," something above and beyond mere subsistence as the fruit of one's efforts. Despite his acknowledgment of life's good things, and even occasions of genuine joy, this opening question seems to imply a negative answer. For in 2:11 he asserts, "I considered all that my hands had done and the toil ['amal] I had spent in doing it, and again, all was vanity [hevel] and a chasing after wind, and there was nothing to be gained [literally, "there was no yitron"] under the sun." What does it all add up to? "Vanity of vanities, says Qoheleth, vanity of vanities! All is vanity" (1:2; 12:8).