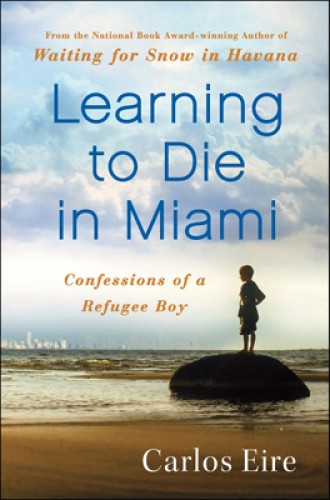

Learning to Die in Miami, by Carlos Eire

Carlos Eire, having won the National Book Award in 2003 with his first memoir, Waiting for Snow in Havana, must have felt author's anxiety as he approached the blank screen a second time. After fearing what he calls the Void all his life, he did what all great writers do—he turned light on it and made it an integral part of his story. "Learning to die" became his phrase for how he was transformed through multiple "deaths" from age 11 to age 60.

The dedication of the book begins, "to the Infant Jesus of Prague, fellow exile," and immediately we enter the territory of the stranger and pilgrim. Eire's parents sent him out of Cuba in 1962, along with his brother Tony, as part of a cold war operation called Pedro Pan, in which 14,000 children were airlifted to Miami to free them from Fidel Castro and communism. Little Carlos carried a single book, a brown leather copy of Thomas à Kempis's The Imitation of Christ. The book plays an important role in his story, first as a totem of his own past life, then as an indecipherable mystery and later as an agent of regeneration. But this is no sweet religious-tract memoir. This is the story of a fighter, someone whose central drama pits life against death, Presence against absence and hope against despair. "Dukes up" is one of his favorite phrases.

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

Eire pulls us into a story about death and submission through concrete detail. The first chapter starts with a loathsome chicken sandwich that nuns have prepared to welcome the Cuban children to America. Carlos had never touched chicken meat because chicken flesh seemed revolting, like that of reptiles. He now has entered a new culture both reptilian and resplendent. But he has to enter it alone. He feels dead: "To be utterly alone, forever, and to be painfully aware of one's eternal loneliness, this Hell, at least my Hell, the one I entered that morning for the first of many times."

Eire names this kind of death the Void, a feeling of inescapable loneliness that dogs him all his life. Like a shell-shocked soldier or a crime victim, a child taken away from parents at an early age will replay that trauma throughout life. Yet this story is not a victim's story. Carlos gains agency in many ways through ingenuity, relationships with teachers and friends and, above all, a sense of humor. He feels the shame many immigrants feel, especially those with aristocratic backgrounds. In Cuba before Castro, his parents were members of the elite.

Even as a boy, Eire viewed the players in his story with a twinkle in his eye. He excelled especially at two forms of humor—name calling and pop-culture allusions. He seldom referred to his native land as Cuba. Rather, he made up labels like Castrolandia and hurled a different capitalized epithet at Castro and Kennedy every time he wanted to blame them for something new. Unable to detect accents in a new language, Carlos listened very carefully to his role models on TV—Andy Griffith and the Beverly Hillbillies.

Looking back at his parents from America, Carlos renamed them also. His father became Louis XVI for his quixotic tastes in religion and for his ineffectual regency. His mother, naturally, became Marie Antoinette. As he recounts his move from the home of a loving, well-to-do Jewish family to a hellhole where six or so foster children lived under a small roof provided by a terrifying couple, Eire manages an amazing feat. He depicts the graphic horror of living in a cockroach- and rat-invested hovel while poking fun at the terrorist-surrogate parents, whom he calls Lucy and Ricardo in an ironic comparison to the stars of I Love Lucy. Carlos and Tony eventually moved to their uncle's home, then set up a Chicago home with their mother after she managed to leave Cuba. The story of their hardships always contains a halo of humor, which was an excellent coping mechanism for Carlos at the time and is now a way to relieve tension for the reader.

One reason humor works so well in accounts of spiritual journeys is that it connects more to grace than to works. Eire could have used the same facts of his life to construct a Horatio Alger tale of hard work leading to the American dream. He doesn't, even though the dream is there, and he points out that his mother works as hard as any Calvinist. In one section, Eire even derides himself and all his high scholastic achievements because he hasn't yet found the pearl of great price, his true self. Most of all, he hasn't yet found a way beat the Void—though his brown book contains great advice: "He who knows best how to suffer will enjoy the greater peace, because he is the conqueror of himself, the master of the world, a friend of Christ, and an heir of heaven."

Images of grace abound in Learning to Die in Miami. Chief among them are snow and various kinds of trees. To a young boy raised in the tropical Catholic Church, snow looks and feels like the host held up by the priest, then dissolving on the tongue. Trees—palms, oaks, evergreens—represent grace also, a more solid form; Eire finds Druid-like divine comfort in them.

Eire has crafted this book beautifully. Each chapter could exist as an essay in its own right, beginning with a memory—often a concrete image like a sandwich or a sprinkler or a car—and moving into narrative, flash forward, touching on the theme of death in some new way, and coming to a profoundly satisfying conclusion, which almost always consists of a repeated phrase that either first appeared at the beginning of the chapter or was tucked unobtrusively somewhere in the middle, to await its curtain call at the end. This is autobiography as poetry in motion in time and space. This is childhood memoir integrated into the entire story of a life, much richer than pure reminiscences of growing up long ago.

One chapter, "Beyond Number," consists of a Whitman-like catalog of 13-year-old Carlos's happinesses and attachments, which are heightened ecstasies because he already has intimations, from reading The Imitation of Christ, that they are not permanent and that he will need to let them go. And then it happens:

Before I can do anything, in a flash, a Presence fills the room, and expands it to the size of the entire universe. Light streams in. The Void crashes into this Presence, and evaporates, instantly, in the blinding glow. The force of the impact throws me off balance, physically, and hurls me to the ground, on my knees, right there, by my uncle's chair, under Protestant Jesus, sweet Midwestern Christ, ever so human and infinite and present. As I gaze at him, the goddamned Void hisses and spits and sputters and vanishes.

The last chapters of the book rise to pure lyricism, swooping over the last 48 years, picking up bits and pieces of memory. Fragments from deaths of the past blow into the book's ending like a blast off Lake Michigan.

This is a winsome book but not an easy one. If you want a good story, you'll find it here. But the best rewards of reading require both grace and struggle, following the author's own brilliant path.