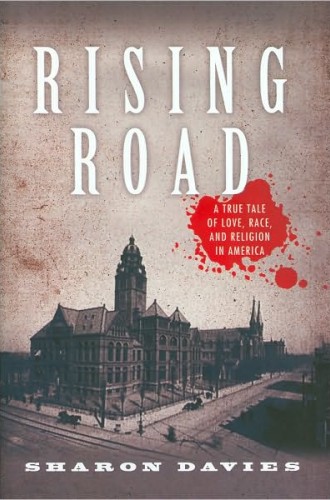

Murder at the rectory

In the summer of 1921, a Methodist minister fatally shot the most prominent Catholic priest in Birmingham, Alabama, on his rectory porch in broad daylight.

The motive was obvious. That day, Father James Coyle had performed the wedding of Edwin Stephenson's 18-year-old daughter, Ruth, to Pedro Gussman, a Catholic Puerto Rican laborer more than two decades her senior. After killing Coyle, Stephenson promptly walked from the rectory to the nearby courthouse and confessed to the crime.

Sharon Davies skillfully traces how an open-and-shut murder case unraveled. That the outcome seemed foreordained did not inhibit Davies from writing a gripping trial history.

Davies makes vivid the pervasive anti-Catholicism of the early 20th-century American South. Some readers will be familiar with earlier instances of anti-Catholic violence, such as the 1834 burning of a Massachusetts convent and the 1844 Philadelphia "Bible riots." Davies demonstrates that vicious and potentially violent anti-Catholicism persisted in parts of the United States for another century. Alabama legislators passed a law in 1919 that empowered authorities to search convents without obtaining a warrant in order to make sure that Catholics were not kidnapping Protestant girls and turning them into nuns. In Birmingham, a Baptist minister who was an avowed opponent of "Romanism" declared that the Catholic Church was training a private army to "make America Catholic."

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

The anti-Catholicism did not go uncontested. Many Alabamans, including the governor, criticized the not-guilty verdict in the Stephenson case and wanted to dissociate their state from charges of religious bigotry. Still, Edwin Stephenson shared the anti-Catholic fears of many Alabama Protestants. He was a minister (technically, a "local deacon") of the northern Methodist Episcopal Church. Known as the "Marrying Parson," he made a living in Birmingham by soliciting business from eloping couples at the county courthouse. The anti-Catholic animus of Stephenson and his wife, Mary, were probably heightened by their home's location near Coyle's St. Paul's Church. Racial and religious bigotry were part of the air Ruth breathed as a child; one year, she decided to wear her father's Ku Klux Klan robes as a Halloween costume. Enjoying a boom in membership that peaked in the mid-1920s, the Klan targeted not only African Americans but also any other perceived threats to white Protestant nationhood.

The family's proximity to St. Paul's piqued Ruth's curiosity about the objects of her father's hatred. She occasionally slipped into the church and, over the years, became acquainted with some of its parishioners. Shortly after her 18th birthday, Ruth was baptized a Catholic. She converted despite her parents' strenuous attempts to extinguish her interest in Catholicism. According to Ruth, her father beat her, locked her in her room and considered consigning her to an insane asylum.

Perhaps to declare her autonomy from her parents, Ruth married Pedro Gussman, an occasional acquaintance, several months later. In Alabama, it was against the law for a white person to marry a "Negro or any descendent of a Negro," but there were no legal barriers to Ruth's marriage because the law regarded Gussman as white. Still, in the eyes of many "old-stock" Americans, Puerto Ricans (and Mexicans, Italians and Jews) occupied an ambiguous racial middle ground.

A few hours after Father Coyle performed the ceremony, Stephenson shot him. Stephenson absurdly claimed that he had fired in self-defense after the priest had gone inside the rectory to fetch a weapon and had threatened him. Despite his apparently flimsy claims, Stephenson's lawyers served him well. The leading light of the defense team was Hugo Black, a future member of both the Klan and the Supreme Court. (Black later joined the 1967 Loving v. Virginia decision overturning state bans on interracial marriage, but in 1921 he did not hesitate to raise the specter of race.) "There are twenty mulattoes for every Negro in Porto Rico," Black told the jury in his closing arguments, overtly appealing to fears of interracial marriage. It took the jury four hours to find Stephenson not guilty.

What remains unexplained and perhaps unknowable is exactly why those 12 jurors—apparently all Protestants—acquitted Stephenson. Did they all loathe Catholics? Did they regard Gussman as black? Inexplicable as it seems, did they find Stephenson's claim that he fired in self-defense credible enough to cast reasonable doubt on the prosecution's allegations? Most likely the jurors shared the belief of much of the state's press: that men possessed an inherent right to defend their homes from unwanted foreign influences, be they racial or religious. Since the jurors kept their reflections to themselves, though, we will never know exactly why Stephenson was set free.

Rising Road provides us with lessons for our own time. Muslims in the United States today face many of the same obstacles that Catholics faced in the 20th century—ignorance of their religion, suspicion of disloyalty and violence, and fear that their growing numbers might destabilize American society. The fact that the United States mostly transcended the bigotry faced by Birmingham Catholics in the 1920s, however, provides reason for long-term optimism.

Many of us, moreover, have faced or will face a situation akin to the dilemma encountered by Edwin and Mary Stephenson. Davies writes that they wanted Ruth, their only child, "to share their loves and convictions, as well as their hates and fears." Whatever our religious beliefs and affiliation, and no matter how much we profess tolerance for our children's choices, we want and expect them to embrace our own brand of religiosity.

To an even larger extent than a century ago, the United States is a nation of religious switchers, in which adults frequently change denominations and in which a large percentage of children depart from their parents' religion. How many mainline Protestant parents have reacted with befuddlement or even disdain when their children claim to have found their salvation through evangelical ministries like Young Life and Campus Crusade? How many Protestants of any denomination could generate good will toward a new in-law if their son or daughter married a Mormon? Unless their children join or marry into a cult or organization that places them in immediate danger, a mixture of patience, curiosity and love will surely do the most for the parents' relationship with them and provide the best testimony of the parents' own beliefs. The question of religious tolerance is often most important within the family.