Russian heart

The opening lines of Dostoevsky's Notes from the Underground (1864) can hardly be described as inviting: "I am a sick man. . . . I am a spiteful man. I am an unattractive man. I believe my liver is diseased." Yet generations of readers have been engaged by the writer's exquisite self-awareness, his extreme ambivalences and his complex understanding of life in a dysfunctional society. The book is a touchstone in literary history, social theory, existentialism and theories of neurosis. In a prefatory footnote, Dostoevsky made the bold claim that, though his narrator is imaginary, "it is clear that such persons as the writer of these notes not only may, but positively must, exist in our society, when we consider the circumstances in the midst of which our society is formed."

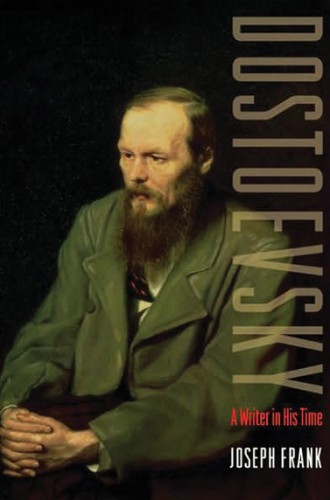

From his earliest works to his consummate achievement, The Brothers Karamazov (1881), Dostoevsky set a new standard for psychological verisimilitude that, as Joseph Frank points out, inspired many writers, perhaps most notably James Joyce, to experiment with ways of getting at truths we often hide, even from ourselves, and at the root causes of psychological and social disorders. Freud considered him the greatest of all novelists.

This one-volume edition of the remarkable five-volume biography Frank completed in 2002 reviews Dostoevsky's psychological, political and spiritual life. Frank points out that most biographers have focused on Dostoevsky's eventful personal life—especially his unjust imprisonment and near-execution in Siberia—and neglected to take sufficient account of the political and intellectual currents that shaped his work. "Indeed, one way of defining Dostoevsky's originality is to see in it [his] ability to integrate the personal with the major social-political and cultural issues of his day."