A review of The Seven Pillars of Creation

Creation has long been a neglected child in biblical-theological studies; it is ground often left to creationists and naysayers. Only in recent years has the Bible's creation theology been addressed in a major way, not least because of the impact of the environmental movement. Alongside this theological shift as been an increasing pace of advancement in scientific understandings of the world. How to relate theology and science has often been a matter of contention in both church and society. This study by William Brown, professor of Old Testament at Columbia Theological Seminary, is an important and positive contribution to an ongoing conversation.

Brown's own scholarship has been a significant factor in these developments. His 1999 book on the biblical theology of creation, The Ethos of the Cosmos: The Genesis of Moral Imagination in the Bible, charted new directions, including explorations of the relationship of ethics and cosmology. His new book continues that study from a somewhat different angle of vision, explicitly integrating biblical and scientific viewpoints. The result is a learned treatment of creation that sets a very high standard for the next generation of scholars probing this theme.

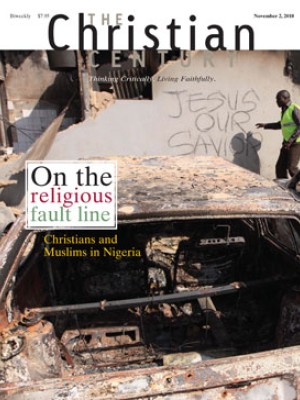

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

The book's title is drawn from the seven pillars of creation in the Old Testament (see Prov. 9:1), each of which adds a distinctive contribution to the manifold nature of creation: the two accounts of creation in Genesis 1-3; Job 38-41; Psalm 104; Proverbs 8:22-31; and excerpts from Ecclesiastes and Isaiah 40-55. These pillars cannot be homogenized into a single, comprehensive account; they are testimony to divergent biblical views of creation.

Brown begins with a thoughtful introduction that addresses issues of biblical authority and hermeneutics and offers a sampling of ancient Near Eastern literature. The book incorporates Brown's own translation of each text, 60 pages of notes and an extensive bibliography.

Brown's purpose is cross-disciplinary: "to explore how to read what the Bible says about creation" in conversation with science. His writing is inviting to nonexperts, which include this reviewer, who yearn to know more about engaging biblical faith and science in constructive rather than confrontational ways. He understands that "though the terrain between science and biblical faith may be filled with intriguing connections awaiting exploration, it is also riddled with disjunctions or collisions, claims made by the biblical text about the world that conflict with the findings of science." Both, however, "lead to opportunities for fresh dialogue and for appropriating the ancient creation traditions." For example, "evolution adds a developmental depth and open-endedness to what the Bible's creation traditions say about nature, including ourselves."

Each chapter is shaped by three interrelated steps: Brown elucidates the text's perspective on creation (the world of the text and the world behind it); associates the text's perspective on creation with the perspective of science (the world of the reader informed by science); and, returning to the text, appropriates the text in relation to science and science in relation to the text ("a hermeneutical feedback loop," not a "hermeneutic of harmonization"). In this last step Brown takes up particular passages and rereads them in dialogue with science. One reviewer commented that reading Brown's book is like reading with the journal Science in one hand and the Bible in the other.

Brown's study of Genesis 1-3 is the most thoroughgoing of his textual treatments. He treats the two creation accounts as separate pillars, and his discussion has strong theological emphases. This reader wonders what insights would have emerged had he treated the two accounts as one; canonically, it could be argued that such a combined account is a single pillar of creation—or a third one altogether.

In the first Genesis account, royal images for God are present, but they are not strong; "Nowhere does God dominate or conquer." God is presented as "thoroughly interactive" with already existing creatures. The language of sovereignty is used, but the descriptors do not correspond to common definitions of that word. Contrary to common opinion, the first chapter of Genesis presents "a skewed symmetry." This observation provides one of many links to scientific understandings: "Perfect symmetry makes for a lifeless universe. Variation, by contrast, constitutes the story of cosmic evolution as it does the Genesis story of creation." Or, chaos theory "finds an ancient precedent in Genesis as an essential, constructive part of creation's evolving order." The "days" of creation, on the other hand, cannot be so readily linked with scientific perspectives.

Regarding the second Genesis account, Brown offers numerous valuable insights: the tree from which the humans ate was the tree of the knowledge of "good and bad" (a helpful translation); God's responses in 3:14-19 are consequences that reflect the author's time (they are not punishments); in eating of the tree the humans lost not immortality itself but the chance to gain immortality (3:22); the creative process in both Genesis and the scientific record is messy; suffering is not solely an effect of the Fall.

On the other hand, some of what Brown claims seems unlikely: that Adam did not become "fully a 'man'" until woman was created because the text speaks more fully of the creation of the female than of the male; that the snake's assurance to the humans that they possess "divine status" says too much about the result of their eating, given that the same language is used by God in 3:22: that they did not become "fully human" selves until they ate of the tree—which was a "necessary choice." I came away from this section with a sense that Brown's efforts to find commonness between Genesis 2-3 and science were too eager, despite the "collision" he often sees.

Brown's study of Job speaks helpfully of the book as a "thought experiment." He writes that the God speeches contain "not only questions, but also information, and plenty of it," and that the book is "a powerful testimony to biodiversity." Psalm 104 speaks of a joyful, playful God who created a world "made exquisitely inhabitable for many and varied forms of life." The "destruction of natural habitats across land and sea takes us," he writes, "one step closer to diminishing God's joy."

The study of Proverbs points out some tension between Wisdom's instrumentality in the creation of the cosmos (3:19-20) and her nonparticipation in the task of cosmic construction, but rather "play" within it (8:22-31). Qoheleth, the most unconventional biblical perspective, "finds more to dissemble than to assemble"; it is a protest against creation's pointless, runaway pace, but also "an affirmation of creation's simple, life-sustaining provisions." In Isaiah 40-55, Brown writes, "God continues to create, and novelty is the norm" in both creation and history. Brown links Isaiah's new creation (including new developments in monotheism) with the contemporary theme of "emergence . . . an orderly unfolding of the world, but an unfolding rich in novelty."

Brown's concluding chapter provides key insights from his analysis and a stirring discussion of the environmental implications of his study. Through the Bible's encounter with science, its "meaning undergoes change: it is extended, deepened, supplemented, narrowed, and transformed." The reader's encounter with this impressive book will certainly also mean participation in a changed and more enlightened appreciation of these biblical texts.