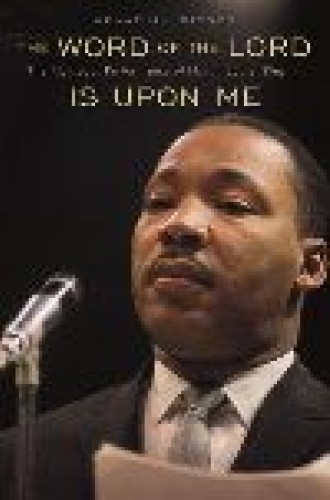

The Word of the Lord Is upon Me: The Righteous Performance of Martin Luther King Jr.

Last year marked the 40th anniversary of the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr., and anyone who followed the media coverage of that occasion understands all too well that the identity of the civil rights leader is fiercely contested. American pop culture idolizes King as an optimistic dreamer, conservative politicians depict him as a color-blind universalist, and leftist scholars paint him as an ethnocentric black prophet. And these are just three of many points of view.

Jonathan Rieder, a professor of sociology at Barnard College, has boldly entered this raging and race-conscious debate, and we should be grateful for his contribution. It is arguably the most creative book about King to date.

Rieder offers neither the typical narrative of King’s life nor a predictable analysis of his theology and politics. The Word of the Lord Is upon Me is part sociology, part anthropology, part linguistics—and an altogether illuminating study of the various forms of King’s language (“jokes, eulogies, sermons, speeches, chats, storytelling, exhortations, jeremiads, taunts, repartee, confessions, lamentation, complaints, and gallows humor”) and of the intriguing ways he used words to hide and reveal his “inner states” in various contexts.

With a remarkable gift for nuance, Rieder ends up arguing that King was “a ‘postethnic’ man who could articulate his sense of self by drawing from a rich repertoire of rhetorics and identities.” That’s a bold thesis—at least in part. The less intriguing part is Rieder’s mundane claim that King was eclectic in his use of sources and that he revealed different aspects of himself to different audiences. That much is old news, and a bit boring at this point. The more fascinating and controversial part centers on King’s identity as “a ‘postethnic’ man.” In arguing this, Rieder faults James Cone for “flirting with a romance of racial authenticity that seemed to say the real King was the black King, and the black King was the one who talked black, which in Cone’s rendering meant the language of spirituals and the blues.”

It’s not that Rieder wants to downplay King’s blackness. That would be foolish, of course, and Rieder devotes the bulk of his book to showing that King’s “performances”—from front-stage speeches and sermons to backstage banter with friends—gave expression to “the primacy of King’s black core.” Rieder’s sharp analysis leaves no doubt that King was a “brother” for whom blackness became increasingly significant throughout his short life.

But Rieder does want to explode our truncated notions of black culture, and so he contends that “refinement” is every bit as black as “rawness” and that King’s “cultured voice”—the elegant sounds and styles he learned from Benjamin Mays, Vernon Johns and Howard Thurman—is no less black than “the voice of the blues and spirituals.” This is a beautifully nuanced argument, and it does not stand alone; Rieder offers an equally thick take on King’s maleness.

Although Rieder excels at expounding on blackness, nowhere does he give us a tight definition of postethnic. That’s a bit surprising, even if it’s not difficult to tease out the meaning: as a postethnic man, King straddled and transcended racial boundaries—blending black talk and white talk and drawing from identities in both cultures. Rieder goes further, however, when he states in a chapter on King’s sermons that “there are ample hints that blackness for King was in certain respects incidental and interim.”

And this gets us to his claim about the constancy of King’s identity. Rieder’s interpretation of King as a “mix master” who spoke different rhetorics in the same paragraph and performed different identities in the same room suggests that King’s identity was quite fluid. (Unsurprisingly, there is evidence aplenty to suggest that King sometimes collapsed because of the pressures associated with performing so many different identities—preacher, exhorter, counselor, healer, deliverer—to so many different types of people.) But Rieder insists that for all its fluidity, King’s identity was also marked by constancy. “The constant for King,” he writes, “lay beyond language, beyond performance, beyond race. The core of the man was the power of his faith, his love of humanity, and an irrepressible resolve to free black people, and other people, too.”

In his core, then, King was a fervent Christian who mixed unmixable colors and commingled divergent identities so he could make the word come alive—a word of universal love that once demanded that whites and blacks join hands to liberate those King called “our” slave ancestors.

It is here that we bump up against the limits of Rieder’s use of language. On the one hand, he affirms “the primacy of King’s black core,” but on the other he argues that King’s core—his Christian faith—lies “beyond race.” These two points do not fit together very neatly, at least as Rieder explains them, and because of this his creative argument that “brotherhood” and “brotherhood” held together in King—that the “tenets of his powerful and Christian democratic faith were never in competition with his equally powerful sense of black identity”—is not entirely convincing.

There are enough difficult themes in Rieder’s excellent book to exasperate and infuriate most readers. While I found his coupling of King’s universalism and particularism a bit maddening, I was also disappointed by the insufficient attention he pays to issues of economic class. Like races, classes advance their own rhetorics and identities, and although Rieder nods toward this point, his sketch of the civil rights leader would have been all the richer had he delved more deeply into the language King adopted from his middle-class family and friends on Auburn Avenue. King was not just a brother, he was a brother with a buck. And just as he did with racial boundaries, King straddled and transcended class borders throughout his adult life, appealing to the rich, the poor and his own people in the middle.

Other readers will no doubt raise their eyebrows at Rieder’s provocative discussion of King’s “certified credentials as an erotic race man.” When describing King’s “primal identity as a black man,” Rieder repeats the familiar point that “despite his cavorting, King did not stray with white women,” even when they actively solicited his interest. This point seems strangely out of place in a book that explodes our truncated notions of black culture, and perhaps Rieder would do well to reconsider his narrow views on the relationship between sexual preferences and the primal identity of black men. Nevertheless, Rieder does not overemphasize King’s sexual dalliances, and he is right to deal forthrightly with the indisputable role that sexuality played in King’s identity.

In spite of its minor imperfections, The Word of the Lord Is upon Me is magisterial in style, groundbreaking in content and magnanimous in purpose. Rieder “scrambles the racial lines” better than any other King scholar has done thus far, and in doing so he has finally begun to free King’s life and legacy from any of us who would dare to hold onto the civil rights leader as if he were our own—and only our own.