CC recommends

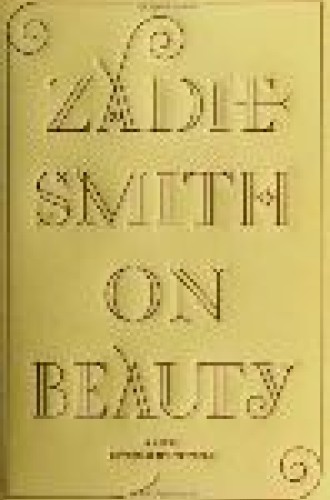

This academic satire is about two professors and their families. Howard Belsey is a white secular liberal, a specialist in Rembrandt, who is engaged in ideological warfare with a visiting professor, Monty Kippes, a conservative Christian scholar from Trinidad. Each character in the story is undermined by his or her self-deceptions. Howard’s attachment to theoretical knowledge seems to preclude understanding or controlling his adulterous behavior. Smith brilliantly draws these and other characters and gently but wittily pierces their illusions and pretensions. Howard’s African-American wife, Kiki, is one of the few characters to offer emotional or moral ballast, along with her son Jerome, who rejects his parents’ secularism for a newfound Christianity.

“I find people confusing,” says Christopher Boone, and soon the reader learns that Christopher means exactly what he says: Christopher is autistic and struggles to understand the human habits of gesturing and of speaking in metaphors, which he takes literally. The reader becomes absorbed not only in the mystery of a murdered dog and a missing mom, but also in the mysterious world of an autistic child. It is an absorbing, plausible book.

The latest in a series of novels about the fictional town of Port William, Kentucky, is perhaps the best. Hannah, in her late 70s, introduces the tale this way: “This is the story of my life, that while I lived it weighed upon me and pressed against me and filled all my sense to overflowing and now is like a dream dreamed.” The lyrical style is deceptively simple: Hannah’s insights, which grow naturally out of her life, are powerful and surprising.

Ishiguro builds his stories with subtle scenes that eventually reveal something dreadful. In Remains of the Day, a butler’s fanatical devotion to his duties leads him to suppress all emotion. In Never Let Me Go, three young people are raised in a special school in the British countryside. Gradually they realize that they have been set apart from society. Eventually they understand that they’ve been raised solely for the purpose of sharing their organs with “normal” citizens. It’s frustrating for the reader that they make no effort to challenge the society or their role in it. That may be an intended effect. The quiet build-up of this story without moral commentary makes it especially disturbing.

The Reverend Jordanna Nash has endured a lot of pain—separation from her husband, stillbirths and the suicide of a parishioner. The novel is a touching portrayal of family life, ministry in a small town, and the relation between a pastor’s personal and professional life. Nash is a fully realized character, at ease with her parishioners’ crises even as she struggles with her own.