Out of Eden

Love, lust, forgiveness, remorse, tolerance, sin, violence and death—these are just some of the themes engaged in The ,Ballad of Jack and Rose. It’s the third feature film by writer-director Rebecca Miller (Personal Velocity, Angela), a former painter and actress who is the daughter of the late playwright Arthur Miller.

This challenging movie, shown mostly in out-of-the-way venues, has been panned by critics who find it less than subtle and not very believable. Have they forgotten that Ingmar Bergman, considered by many the most influential art movie director of the 20th century, made a series of celebrated films that took place on a barren island that served as a microcosm of ethical choices and moral dilemmas? Have we reached the stage where only subtitled symbolism can avoid being labeled “obvious” or “over the top”?

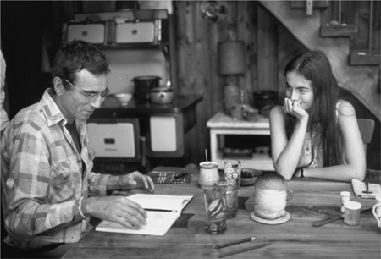

The story takes place in 1986 on an unnamed island off the East Coast of the United States. Jack (played by Daniel Day-Lewis, Miller’s husband) is the last remaining member of a 1960s-style commune. His flower-child wife left him years earlier (he was a bit dogmatic when it came to commune politics). He has been raising and nurturing their daughter Rose (the luminous Camilla Belle), who is 16, sheltered (home-schooled, with no television) and naïve to the ways of the world. Their apparently idyllic existence is threatened on two fronts: Jack is dying of heart disease, and he is falling in love with his own daughter.

Jack invites his sometime girlfriend, Kathleen (Catherine Keener), to move in along with her sons, the sensitive Rodney (Ryan McDonald) and the malevolent Thaddius (Paul Dano). This odd request is ostensibly so they can provide help for Jack as he grows ill, but we sense that he is really building a buffer between himself and his own dark desires.

The film’s second act concerns Rose’s angry response to this instant family. Aiming to get back at her father, she allows Rodney to cut off her long, black hair, shoots a rifle at Kathleen, lets a poisonous snake loose in the house, and gives her virginity to the uncaring Thaddius. She flies the soiled sheet in the wind, where she knows her father will see it.

Subplots abound, including Jack’s ongoing problem with a real estate developer (Beau Bridges), who represents everything that Jack despises.

Miller takes a highly symbolic approach. Rose can be seen as the tender flower that can’t survive outside the garden, Jack as the gardener whose own sins despoil Eden. This style makes for some complex characters and risky plot twists. For instance, Miller asks us to believe that no one minds too much when Jack fires a gun at a construction crew working on one of the new tract houses. And that Rose doesn’t see the need to call a doctor when Jack appears ready to die. Miller is not really interested in a realistic story of a man and his daughter but rather in how idealism can turn to bile.

With its casual attitude toward story and logic, Jack and Rose can be frustrating and infuriating. But for those who understand that Moby Dick isn’t just about chasing a whale, this film is good for what ails you.